Anderson's Angle

Bringing Visual Analogies to AI

Current AI models fail to recognize ‘relational’ image similarities, such as how the Earth’s layers are similar to a peach, missing a key aspect of how humans perceive images.

Though there are many computer vision models that are capable of comparing images and finding similarities between them, the current generation of comparative systems have little or no imaginative capacity. Consider some of the lyrics in the classic 1960s song, Windmills of Your Mind:

Like a carousel that’s turning, running rings around the moon

Like a clock whose hands are sweeping past the minutes of its face

And the world is like an apple whirling silently in space

Comparisons of this kind represent a domain of poetic allusion that is meaningful to humans in a way far beyond artistic expression; rather, it’s bound up with how we develop our perceptual systems; as we create our ‘object’ domain, we develop a capacity for visual similarity, so that – for example – cross-sections depicting a peach and the planet Earth, or fractal recursions such as coffee spirals and galaxy branches, register as analogous with us.

In this way we can deduce connections between apparently unconnected objects and types of objects, and infer systems (such as gravity, momentum and surface cohesion) that can apply to a variety of domains at a variety of scales.

Seeing Things

Even the latest generation of image comparison AI systems, such as Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) and DINO, which are informed by human feedback, only perform literal surface comparisons.

Their capacity to find faces where none exist – i.e., pareidolia – does not represent the kind of visual similarity mechanisms that humans develop, but rather occurs because face-seeking algorithms utilize low-level face structure features that sometimes accord with random objects:

Examples of false positives for facial recognition in the ‘Faces with Things’ dataset. Source

To determine whether or not machines can really develop our imaginative capacity to recognize visual similarity across domains, researchers in the US have conducted a study around Relational Visual Similarity, curating and training a new dataset designed to force abstract relationships to form between different objects that are nonetheless bonded by an abstract relationship:

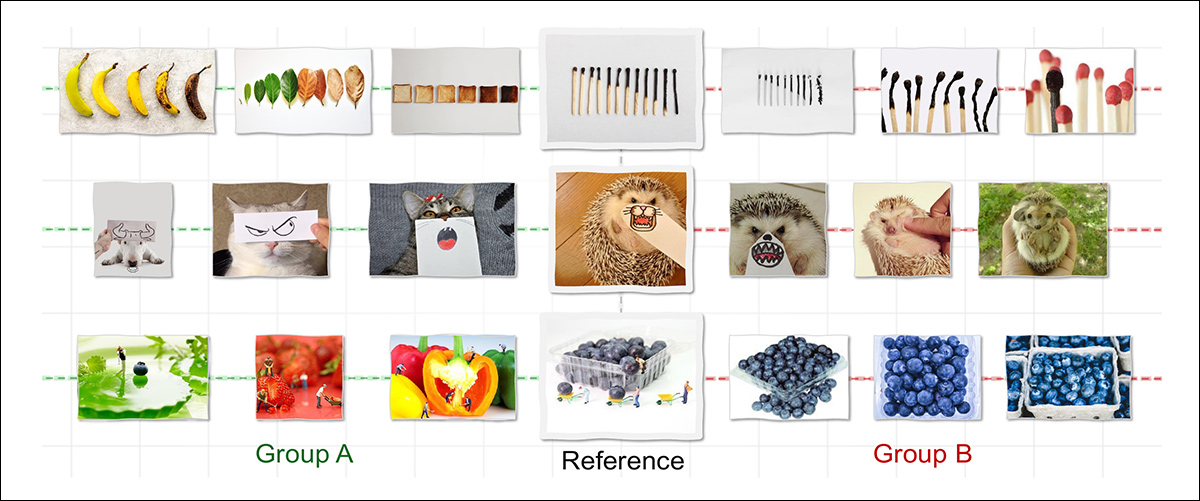

Most AI models only recognize similarity when images share surface traits such as shape or color, which is why they would link only Group B (above) to the reference. Humans, by contrast, also see Group A as similar – not because the images look alike, but because they follow the same underlying logic, such as showing a transformation over time. The new work attempts to reproduce this kind of structural or relational similarity, aiming to bring machine perception closer to human reasoning. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.07833

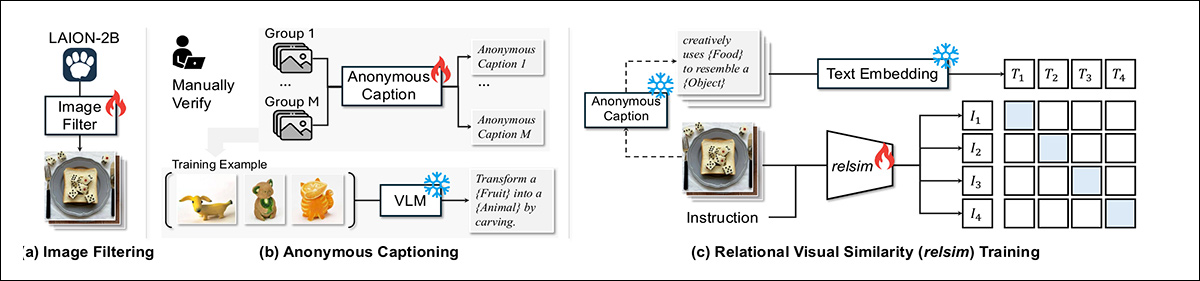

The captioning system developed for the dataset facilitates unusually abstract annotations, designed to force AI systems to focus on base characteristics rather than specific local details:

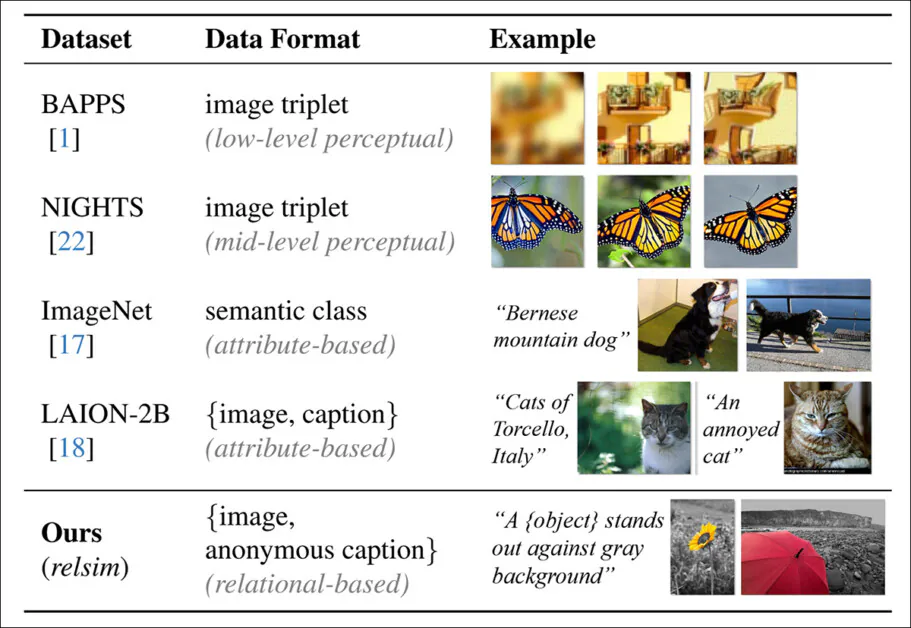

The predicted ‘anonymous’ captions that contribute to the authors’ ‘relsim’ metric.

The curated collection and its uncommon captioning style fuels the authors’ new proposed metric relsim, which the authors have fine-tuned into a vision-language model (VLM).

A comparison between the captioning style of typical datasets, which focuses on attribute similarity, whereas the relsim approach (bottom row) emphasizes relational similarity.

The new approach draws on methodologies from cognitive science, in particular Dedre Gentner’s Structure-Mapping theory (a study of analogy) and Amos Tversky’s definition of relational similarity and attribute similarity.

From the associated project website, an example of relational similarity. Source

The authors state:

‘[Humans] process attribute similarity perceptually, but relational similarity requires conceptual abstraction, often supported by language or prior knowledge. This suggests that recognizing relational similarity first requires understanding the image, drawing on knowledge, and abstracting its underlying structure.’

The new paper is titled Relational Visual Similarity, and comes with a project website (see video embedded at the end of this article).

Method

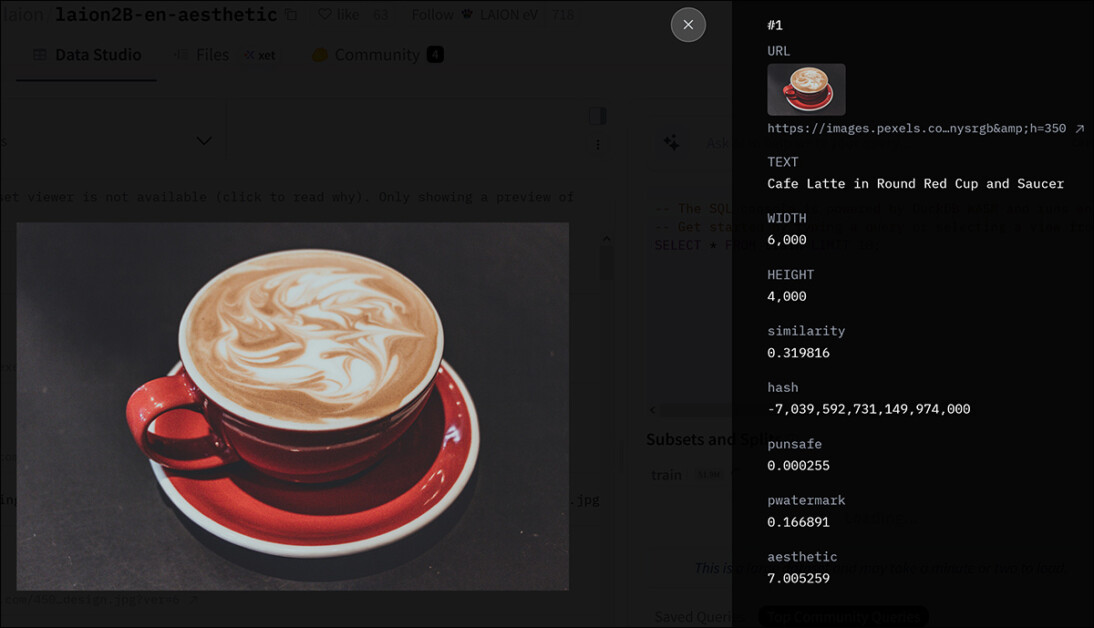

The researchers used one of the best-known hyperscale datasets as a starting point for their own collection – LAION-2B:

Metadata for an entry in the LAION-2B collection. Source

114,000 images likely to contain elastic relational structures were extracted from LAION-2B, involving the filtering of the many low-quality images that are present in the minimally-curated dataset.

To create a pipeline for this selection process, the authors utilized Qwen2.5-VL-7B, leveraging 1,300 positive and 11,000 negative human-labeled examples:

The relsim system is trained in three stages: filtering images from LAION-2B for relational content; assigning each group a shared anonymous caption that captures their underlying logic; and learning to match images to those captions using a contrastive loss.

The paper states:

‘Annotators were instructed: “Can you see any relational pattern, logic, or structure in this image that could be useful for creating or linking to another image?”. The fine-tuned model achieves 93% agreement with human judgments, and when applied to LAION-2B, it yields N = 114k images identified as relationally interesting.’

To generate relational labels, the researchers prompted the Qwen model to describe the shared logic behind sets of images without naming specific objects. This abstraction was difficult to obtain when the model saw only one image, but became workable when multiple examples demonstrated the underlying pattern.

The resulting group-level captions replaced specific terms with placeholders such as ‘{Subject}’ or ‘{Type of Motion}’, making them broadly applicable.

After human verification, each caption was paired with all images in its group. More than 500 such groups were used to train the model, which was then applied to the 114,000 filtered images to produce a large set of abstract, relationally annotated samples.

Data and Tests

After the extraction of relational features with Qwen2.5-VL-7B, a model was fine-tuned on the data using LoRA, for 15,000 steps, via eight A100 GPUs*. For the text side, relational captions were embedded using all-MiniLM-L6-v2 from the Sentence-Transformers library.

The dataset of 114,000 captioned images was split into 100,000 for training and 14,000 for evaluation. To test the system, a retrieval setup was used: given a query image, the model had to find a different image from a 28,000-item pool that expressed the same relational idea. The retrieval pool included 14,000 evaluation images and 14,000 additional samples from LAION-2B, with 1,000 queries randomly selected from the evaluation set for benchmarking.

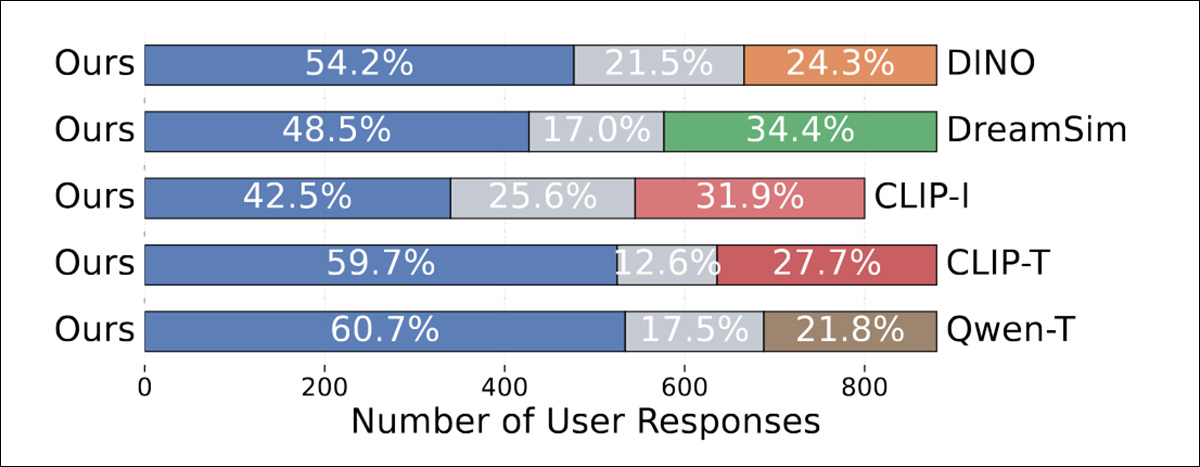

To evaluate retrieval quality, GPT-4o was used to score the relational similarity between each query and retrieved image on a scale from 0 to 10. A separate human study was also run to gauge user preference (see below).

Each participant was shown an anonymized query image with two candidates, one retrieved by the proposed method, the other by a baseline. Participants were asked which image was more relationally similar to the query, or if both were equally close. For each baseline, 300 triplets were created and rated by at least three people each, yielding around 900 responses.

The relsim approach was compared against several established image-to-image similarity methods, including the aforementioned LPIPS and DINO, as well as dreamsim, and CLIP-I. In addition to baselines that directly compute similarity scores between image pairs, such as LPIPS, DINO, dreamsim, and CLIP-I, the authors also tested caption-based methods in which Qwen was used to generate an anonymous or abstract caption for each image.; this then served as the retrieval query.

Two retrieval variants were evaluated, with CLIP-based text-to-image retrieval (CLIP-T) used for text-to-image retrieval, and Qwen-T using text-to-text retrieval. Both caption-based baselines used the original pretrained Qwen model rather than the version fine-tuned on relational logic. This allowed the authors to isolate the effect of group-based training, since the fine-tuned model had been exposed to image sets, rather than isolated examples.

Existing Metrics and Relational Similarity

The authors initially tested whether existing metrics could capture relational similarity:

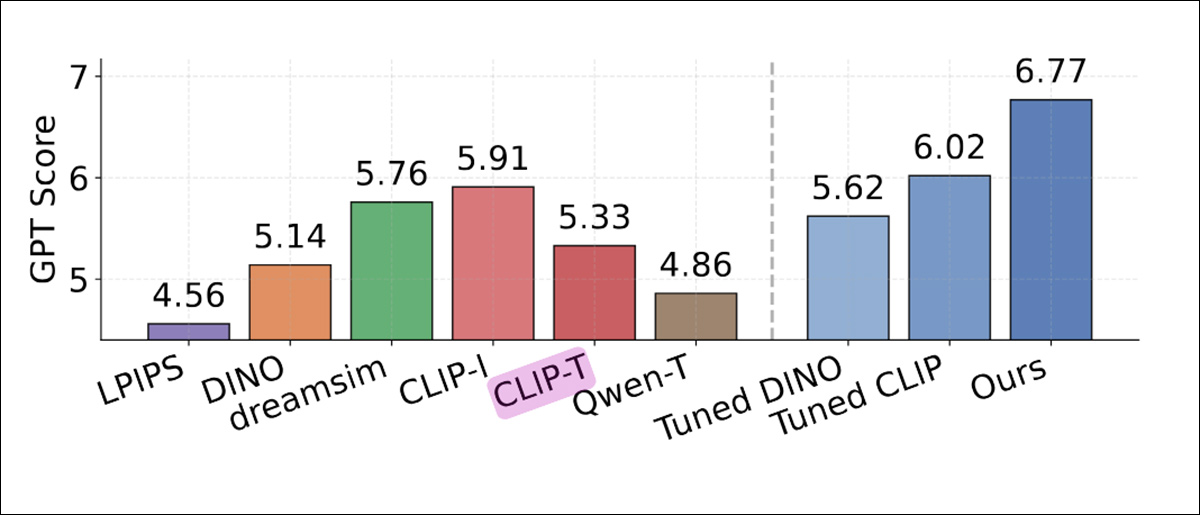

Comparison of retrieval performance as judged by GPT-4o, showing the average relational similarity score for each method. Conventional similarity metrics such as LPIPS, DINO, and CLIP-I scored lower. Caption-based baselines Qwen-T and CLIP-T also underperformed. The highest score was achieved by relsim (6.77, right-most blue column), indicating that fine-tuning on group-based relational patterns improved alignment with GPT-4o’s assessments.

Regarding these results, the authors state**:

‘[LPIPS], which focuses purely on perceptual similarity, achieves the lowest score (4.56). [DINO] performs only slightly better (5.14), likely because it is trained solely in a self-supervised manner on image data. [CLIP-I] yields the strongest results among the baselines (5.91), presumably because some abstraction is sometimes present in image captions.

‘However, CLIP-I still underperforms relative to our method, as achieving a better score may require the ability to reach even higher-level abstractions, such as those in anonymous captions.’

In the user study, humans consistently preferred the relsim method across all baselines:

Relational similarity scores assigned by GPT-4o for each method. Standard similarity metrics such as LPIPS, DINO, and CLIP-I scored lower, and caption-based variants Qwen-T and CLIP-T performed only slightly better. Even tuned versions of DINO and CLIP did not close the gap. The highest score, 6.77, was achieved by the relsim model, trained with group-based supervision.

The authors note:

‘This is highly encouraging, as it demonstrates not only that our model, relsim, can successfully retrieve relationally similar images, but also, again, confirms that humans do perceive relational similarity–not just attribute similarity!’

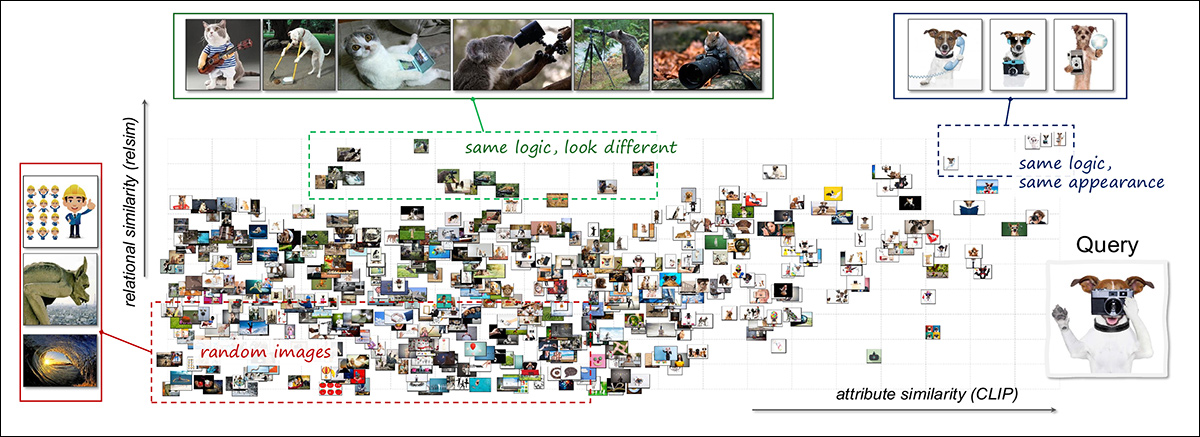

To explore how relational and attribute similarity might complement one another, the researchers used a combined visualization method. A single query image (‘A dog holding a camera’) was compared against 3,000 random images, and similarity was computed using both relational and attribute-based models:

Joint visualization of visual similarity space using relational and attribute axes. A single query image, depicting a dog using a camera, was compared against 3,000 others. Results were organized by relational similarity (vertical) and attribute similarity (horizontal). The top-right region contains images that resemble the query in both logic and appearance, such as other dogs using tools. The top-left contains semantically related but visually distinct cases, such as different animals performing camera-related actions. Most remaining examples cluster lower in the space, reflecting weaker similarity. The layout illustrates how relational and attribute models highlight complementary aspects of visual data. Please refer to the source paper for better resolution.

The results revealed clusters corresponding to different types of similarity: some images were both relationally and visually similar, such as other dogs in human-like poses; others shared relational logic but not appearance, such as different animals mimicking human actions; the remainder showed neither.

This analysis suggests that the two similarity types serve distinct roles and yield richer structure when combined.

Use Cases

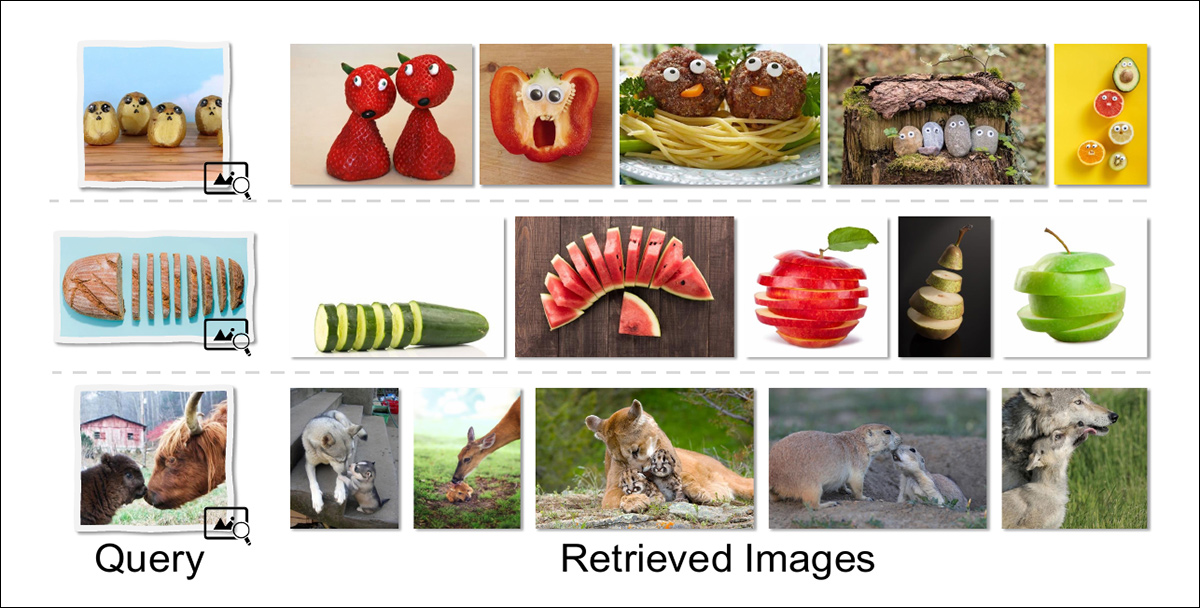

The paper also explores some possible end-use cases for relational similarity, including relational image retrieval, which allows for image search more aligned with humans’ own creative way of looking at the world:

Relational retrieval returns images that share a deeper conceptual structure with the query, rather than matching surface features. For example, a food item styled to resemble a face retrieves other anthropomorphic meals; a sliced object yields other sliced forms; and scenes of adult-offspring interaction return images with similar relational roles, even when species and composition differ.

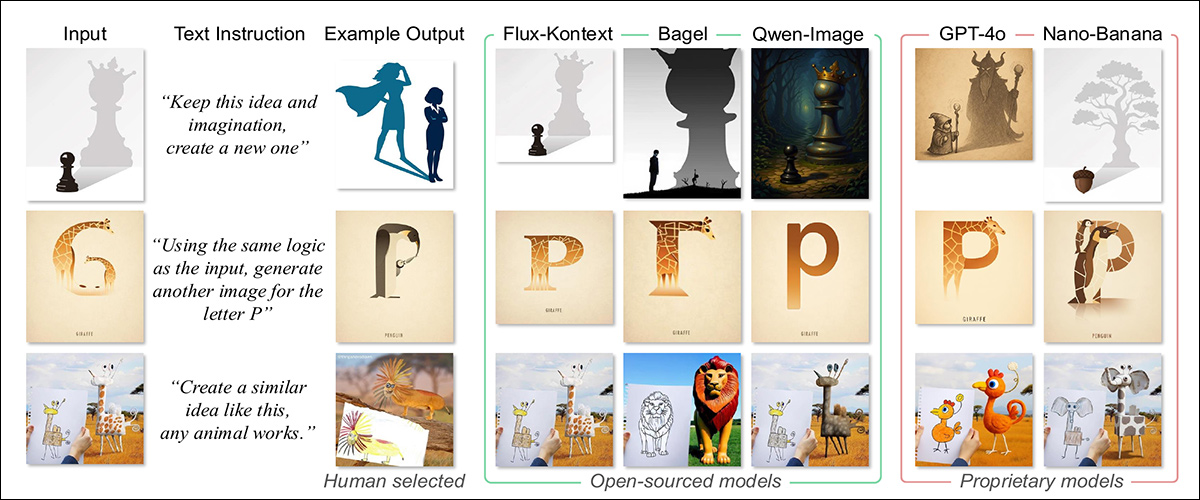

Another possibility is analogical image generation, which would allow the synthesis of queries that use relational structures rather than direct descriptions. In a comparison of results obtained from the current generation of state-of-the-art text-to-image models, we can see that the results of such an approach is likely to be more diverse:

Given an input image and a relational prompt, models were asked to generate a new image expressing the same underlying concept. Proprietary models produced more faithful analogies, preserving structural logic across large changes in form, while open-sourced models tended to regress to literal or stylistic matches, failing to transfer the deeper idea. Outputs were compared against human-curated analogies, which exemplified the intended transformation.

Conclusion

Generative AI systems would, it seems, be notably enhanced by an ability to incorporate abstract representation into their conceptualizations. As it stands, asking for concept-based images such as ‘anger’ or ‘happiness’ tends to return images styled from the most popular or populous images that had these associations in the dataset; which is memorization rather than abstraction.

Presumably this principle could be even more beneficial if it could be applied to generative writing – particularly analytical, speculative or fictional output.

Press to play. Source

* An A100 can have 40Gb or 80GB of VRAM; this is not specified in the paper.

** Authors’ citations redundant and excluded.

First published Tuesday, December 16, 2025