Anderson's Angle

AI Chat Models Can Run Up Costs Through Endless Rambling

Popular AI chat models secretly waste huge amounts of paid tokens on pointless verbiage. Affected models actually know they are doing this, but cannot stop themselves.

Large Reasoning Models (LRMs) such as ChatGPT-5 and Google Gemini charge more for reasoning – walking through a problem step-by-step, which uses significantly more computing power than just quickly predicting the next word. The simulated reasoning process takes longer and costs more to run; consequently, users end up paying for that ‘extra thinking-time’.

However, if you’ve used a state-of-the-art LLM lately, you might have noticed that your allocation of tokens is often spent on verbiage and cruft, rather than focusing in on solving the problems that you are posing to the model. This can take the form of excessive sycophancy, prolix and/or redundant answers – or even a kind of ‘rambling’, as if the AI had been caught on the spot and is trying to gabble its way out of an awkward situation.

Naturally, we would prefer that our LLMs concede defeat, follow or offer alternative paths, or request clarification. But even getting an AI of this kind to admit that they do not know an answer is a considerable challenge by itself.

In the meantime, users on lower or free tiers can find themselves having burned through their tokens at a fast rate, no matter how targeted or economical their queries and interactions were, because the AI itself loves to talk; and, in this case, talk isn’t cheap.

Word Salad

In regard to the aforementioned ‘rambling’, a new academic collaboration is offering a rationale and a solution, by proposing that LLMs with reasoning capabilities are prone to burn through your tokens when they get caught in a ‘word salad’ loop – a state of befuddlement where the reasoning process gets lost in recursive blind alleys – on your dime*.

The researchers behind the new paper have found that a significant portion of the tokens processed in a typical LLM consists of repetition and redundancies – and that the model itself seems to understand that it is in trouble, even though it is unable to stop the costly loop.

The paper states:

‘We show that a significant portion of these tokens are useless self-repetitions – what we call “word salad” – that exhaust the decoding budget without adding value. Interestingly, we observe that LRMs are self-aware when trapped in these loops: the hidden states of <\n\n> tokens trailing each reasoning chunk exhibit patterns that allow us to detect word salad behavior on-the-fly via a single-layer linear classifier.

‘Once detected, a simple chop appended by a straightforward regeneration prompt yields substantial length savings with minimal quality loss.’

The solution offered by the new work is an intervention that can cut off the spiraling process of an errant reasoning LLM in an on-the-fly manner, without inclusion in training data, or any of the damage that can result from fine-tuning. The framework, titled WordSaladChopper, has been publicly released at GitHub.

Though the initial work concentrates DeepSeek variants such as entries in the Qwen and Llama series, the paper asserts that the unwanted behavior is likely applicable to a far larger swathe of similarly-architected reasoning models (including popular API-only offerings such as ChatGPT and Google Gemini).

As the paper notes, prior offerings such as Demystifying Long Chain-of-Thought Reasoning in LLMs and Small Models Struggle to Learn from Strong Reasoners likewise use the small number of publicly available Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning models to establish a wider issue among this class of models†:

‘[LRMs] tend to waste an enormous amount of decoding budget, simply by repeating themselves verbatim, with slight variations, or engaging in endless enumeration of cases until all budget has been [expensed] – we refer to such behavior as Word Salad, a term often used to mock public spokespersons for giving long-winded, jargon-filled responses that ultimately lack substance or clear meaning.

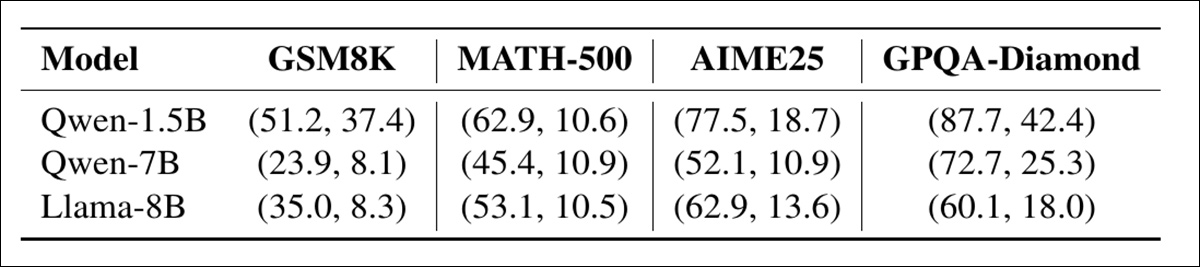

‘The “Original” column in [the table below’] shows that when answering GPQA-Diamond, we observe 55%+ of tokens generated by DeepSeek-R1-Distill models are marked as “word salad tokens,” where they do not add value from a semantic standpoint.’

![The share of output tokens identified as semantically redundant when answering GPQA-Diamond. WordSaladChopper reduces this overhead from over 55% to under 6% across all tested DeepSeek-R1-Distill models, the authors attest. [ Source ] https://arxiv.org/pdf/2511.00536](https://www.unite.ai/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/table-1.jpg)

The share of output tokens identified as semantically redundant when answering GPQA-Diamond. WordSaladChopper reduces this overhead from over 55% to under 6% across all tested DeepSeek-R1-Distill models, the authors attest. Source

The authors note that attempts to shorten reasoning processes while preserving answer quality has become a strong sub-strand in the research literature, namely long-to-short (L2S); and further observe that while their project aims are similar to a handful of prior initiatives, their own is the first to offer an ad hoc solution that does not require intervention in the training process, model editing, or other possible impositions on the base architecture of an LLM; and to that extent, they believe that their approach should become widespread among applicable systems†:

‘Given its low overhead, strong savings, and the lack of semantic value of word salad tokens, we believe it is not too far-fetched to argue that [Word Salad Chopper] – or a similar component – is a must-have for all LRM applications with user experience in mind ‘

The new paper is titled Word Salad Chopper: Reasoning Models Waste A Ton Of Decoding Budget On Useless Repetitions, Self-Knowingly, and comes from six researchers across the University of Minnesota, Rice University, the Stevens Institute of Technology, and Lambda, Inc.

Prior Considerations

To track the tendency of reasoning LLMs to repeat themselves, the authors split the models’ output into chunks wherever there were double line breaks, then checked how similar each chunk was to earlier ones:

Estimated share of reasoning chunks flagged as word salad under two decoding temperatures (τ = 0.0, 0.6). The classifier marks a chunk as ‘word salad’ when it closely resembles an earlier part of the model’s output, suggesting repetition rather than progress. Results show that this behavior is widespread across datasets and model sizes.

If a chunk was too similar, it was flagged as ‘word salad’ (effectively a useless repetition).

The researchers note that once a model enters ‘word salad’ mode, it is very unlikely to escape from it without external aid, instead remaining in the expensive loop until the user’s decoding budget is spent††:

‘Needless to say, this presents a catastrophic issue to users, as an ideally much shorter thinking section is now maximized with useless repetitions. So the user is essentially paying the maximum cost for a (likely) wrong answer, while enduring the longest end-to-end latency.’

Share of word salad chunks appearing before and after the chopping point (i.e., the moment when repetitive output begins to dominate). Most repetitions occur after this point, showing that once a model enters a word salad loop, it rarely recovers without intervention.

The authors recount their surprise when they discovered that reasoning LLMs††† exhibited signs of being aware of their word-salad state. However, it’s this awareness, and the way that it enters the model’s probable reasoning state, that allows for a system of intervention:

‘The lightweightness of this linear classifier opens the door for on-the-fly detection, where we can effectively intervene with different operations to address models trapped in word salad loops.’

Method

To detect the presence of word salad during inference, the authors trained a simple linear classifier that runs on the hidden state of each double newline token.

Any chunk occurring after the model entered a repetition loop was treated as word salad, with this cutoff (referred to as the chopping point) used to label the training data. One thousand reasoning traces were generated using the S1 benchmark, and each trace split into newline-separated chunks.

Conceptual schema for WordSaladChopper. During generation, the hidden state at each double newline token is analyzed to detect repetitive segments. Once two ‘word salad’ chunks are flagged in a row, generation is halted. A fixed regeneration prompt is then appended, allowing the model to continue and finish its answer without exceeding the budget.

If a chunk was found to be highly similar to an earlier one, it was labeled as word salad. Once the earliest sustained repetition was identified, all subsequent chunks were also labeled as word salad to reflect the persistence of these loops.

The classifier was implemented as a single fully connected layer and trained on the hidden states of the trailing tokens from the final transformer block. A separate classifier was trained for each model, using this data, and no fine-tuning was performed during evaluation.

Data and Tests

Training and inference used four NVIDIA A100 (80G VRAM) GPUs, under the Adam optimizer, with a learning rate of 1×10-2, for 50 epochs.

The evaluation datasets were ‘Grade School Math’ 8000, a.k.a., GSM8K; MATH-500; GPQA-DIAMOND; and AIME25 (2025).

Models tested were DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B; DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-7B; and DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B, all under MIT license.

Metrics used were Accuracy and AUROC.

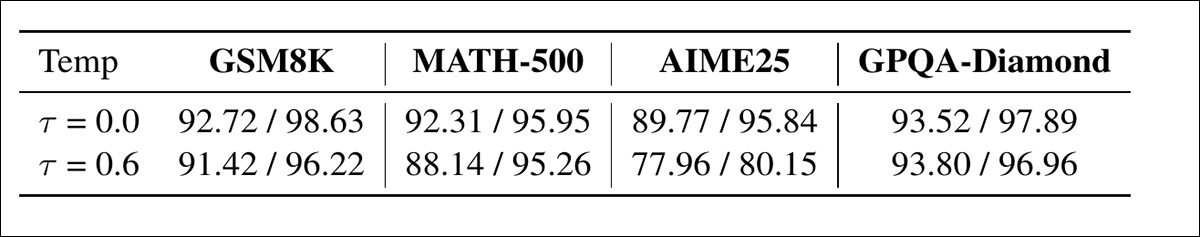

Accuracy and AUROC of the word salad classifier on Qwen‑7B across four benchmarks and two decoding temperatures. High scores confirm that the onset of repetition can be reliably detected from the hidden state of the trailing newline token.

Of the results depicted here, the authors comment:

‘[The results table above] shows that the linear classifier is extremely accurate in detecting the word salad chunks; yet [the results table below] demonstrates that the regeneration prompt helps recover the task accuracy lost from brute-force chopping.’

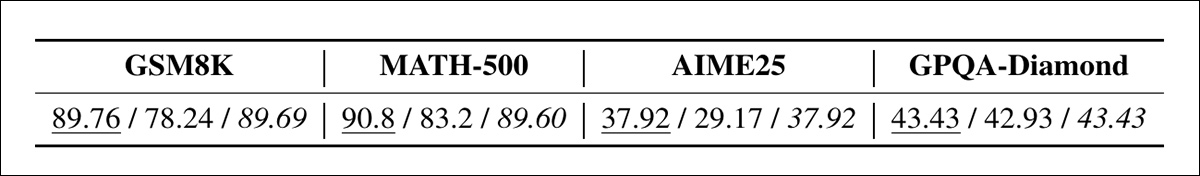

Accuracy of Qwen-7B on each benchmark at τ = 0.6, comparing performance before word salad (Original), after chopping (Chopped), and after applying regeneration (Regenerated). Gains from regeneration are modest but consistent, recovering pre-loop performance in most cases.

In the results table below we can see that WordSaladChopper improved or preserved accuracy while sharply reducing the length of model outputs, by as much as 57%:

When WordSaladChopper is used at greedy decoding (τ = 0), it reduces the length of model outputs, sometimes by more than half, while keeping accuracy the same or slightly better, a performance which remains consistent among different models and tasks (AIME25 is omitted due to predictably unstable results under this setting).

The biggest gains appeared in longer answers, especially on GPQA-Diamond, where nearly half the text was removed without hurting performance. Below we can see similar results when randomness was added during generation:

At higher temperature (τ = 0.6), WordSaladChopper continues to shorten outputs by 10-30 percent, with accuracy remaining stable or slightly improved across all models and benchmarks (AIME25 results are averaged to reduce variance).

Here accuracy stayed stable, with shorter outputs achieved. Across the board, the system continued to work even when the model’s answers became more repetitive; and the authors note that because the classifier only checks one token per sentence, it runs extremely fast, even when used during live generation.

The paper observes that additional strategies in future research along these lines could benefit from granting the model a small regeneration budget after the intervention; continuous application of a WordSaladChopper-style system over regenerations; and forcing an ‘end of think’ token on the model, to demand its best current answer.

Finally, the researchers comment on the quality of the current state-of-the-art in evaluating reasoning models, with a critical tone†:

‘[It] is our honest belief that many efficient reasoning methods appear effective partly because current reasoning evaluation benchmarks have much room for improvement.

‘Should we develop more comprehensive evaluation suites – which we surely will in the future – we expect to see many efficient reasoning methods fail, or behave much differently than their vanilla LRM counterparts.’

Conclusion

At the scale reached by leading systems like ChatGPT, even small shifts in user resource consumption can carry major infrastructure, logistics, and cost implications. This makes efficiency a shared priority for both providers and the broader research community.

If implemented, the new and lightweight system proposed in the paper (which must be custom-trained to each novel model architecture) could prevent the pointless burning of tokens – which can give the customer the impression that the vendor is ‘bleeding out’ their allocation in a profligate or deceptive way. In truth, the vendor fares better by providing useful rather than redundant output, which costs the same, in compute terms, as a word salad.

* Though we will not expound on it here, this extends also to locally-hosted models, which may also be corporate as well as hobbyist, and where the electricity and productivity losses of word salad may be a factor worth noting.

† As usual, all emphasis is the authors’, and not my own. Where applicable, their inline citations have been converted to hyperlinks by me.

†† Here we must acknowledge that frameworks and APIs can allocate ‘sub-budget’ to queries, so that one query is not necessarily capable of burning through a day’s allowance of tokens – but this is not common practice, nor commonly discussed among API-only providers.

††† I am not generally prepared to adopt the authors’ use of ‘LRMs’, as this is not currently a mainstream abbreviation, so I will use other terminology in this article, as necessary.

First published Thursday, November 6, 2025