Anderson's Angle

Identifying AI Model Theft Through Secret Tracking Data

A new method can secretly watermark ChatGPT-like models in seconds without retraining, leaving no trace in general output and surviving all feasible removal attempts.

The subtle difference between watermarking and ‘copyright-baiting’ is that watermarks – whether overt or hidden – are usually intended to appear throughout a collection (such as an image dataset) as a ubiquitous obstruction to casual copying.

By contrast, a fictitious entry is a small segment of text, usually a word or a definition featured in a large and relatively generic collection, designed to prove theft. The idea is that when the entirety of the work is illegitimately copied, either in itself or as the basis for a derivative work, the presence of a ‘unique’ and spurious fact, planted by the original proprietor/s, will easily reveal the act of theft.

In terms of adding watermarks to Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision Language Models (VLMs), the extent to which output is meant to contain these tell-tale signs is often split among these two aims: to ensure that all or most output contains a manifest or latent watermark; or to ensure that a ‘secret token’ can be recovered which proves theft – but which does not appear in regular output from the model.

The Weight(s) of Evidence

The latter approach is addressed in an interesting new collaboration between China, Italy, and Singapore; a work that aims to provide such a disclosure method to open source models, so that they cannot easily be commercialized, or otherwise used in ways that the original license does not permit.

For instance, a model’s original license may insist that anyone can profit from the work so long as they make their own alterations or amendments publicly available under the same generous license terms – but a company may wish to gate-keep their ‘tweaks’ (such as fine-tuned versions), to generate a moat where none is really allowed.

The majority of research in this line is occupied with detection routines related to closed-source, API-only models, or models for which only optimized (quantized) weights are available; and which are therefore more difficult to efficiently edit and alter in the way the new paper proposes (because there is no direct access to the architecture of the model itself).

This attention to FOSS releases is, perhaps, unsurprising from the Chinese research sector, since China’s AI output has over the last year been hallmarked by generous full-weight* releases of models that at least rival the more ‘locked-down’ western equivalents.

The new approach, titled EditMark, distinguishes itself by not requiring either that the model be fine-tuned to add the ‘poisoned’ data, nor trained from the outset with the data included.

This has several benefits: one is that any ‘tell-tale’ data included in the training dataset, once discovered and disclosed, will no longer be effective, since it can be directly targeted by attackers; but to attack EditMark, a malefactor would need to know which layer of the model to target, and what kind of approach has been taken. This is an unlikely scenario.

Secondly, the approach is quick and cheap, taking a matter of seconds (rather than days or even weeks) to apply to a trained model, obviating the severe expense of fine-tuning (which increases linearly with the size of the model and the data to be applied).

Finally, the approach does significantly less damage to the normal operation of the targeted model than either fine-tuning or prior edit methods.

In tests, EditMark – which embeds mathematical queries with multiple possible answers into the model weights – achieved an extraction rate of 100%.

The authors state:

‘Comprehensive experiments demonstrate the exceptional performance of EditMark in watermarking LLMs. EditMark achieves remarkable efficiency by embedding a 32-bit watermark in less than 20 seconds with a 100% watermark extraction success rate (ESR).

‘Notably, the watermark embedding time is less than 1/300 of fine-tuning (average 6,875 seconds), which highlights EditMark’s effectiveness in implementing high-capacity watermarks with unprecedented speed and reliability.

‘In addition, extensive experiments validate the robustness, stealthiness, and fidelity of EditMark.’

The new paper is titled EditMark: Watermarking Large Language Models based on Model Editing, and comes from eight authors across the University of Science and Technology of China, the University of Siena, and CFAR/IHPC/A*STAR at Singapore.

Method

The EditMark approach comprises four components: a Generator, an Encoder, an Editor, and a Decoder:

The EditMark pipeline embeds a watermark by editing a model to answer specific mathematical questions in a way that encodes hidden identifying information. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.16367

The Generator uses a pseudo-random seed to construct multiple-answer math questions; the Encoder selects answers based on the watermark, which are then embedded into the model via a specialized editing process. Once the edited model is released or misused, the watermark can be extracted by asking the same questions and decoding the pattern of responses.

Subsequently, the Editor modifies the model weights so that, when asked these seeded questions, the model reliably produces the target answers, embedding the watermark directly into its behavior. The Decoder then recovers the watermark by feeding the same questions to the suspect model, and translating its answers back into the hidden signature.

Threat Model

The paper’s threat model assumes that watermarking is done in a white-box setting. Though this is not usually a good sign in security-related research, here this is normal, since the method aims to protect owners that have full access to their own work.

The attacker is also assumed to have white-box access after obtaining the model, meaning they can modify it (e.g., by pruning or fine-tuning). Again, this scenario is normal and expected in the case of a FOSS release. However, the attacker is not privy to the watermark extraction process or the schema used, and can only find this method by inference and experimentation (or else, leaks).

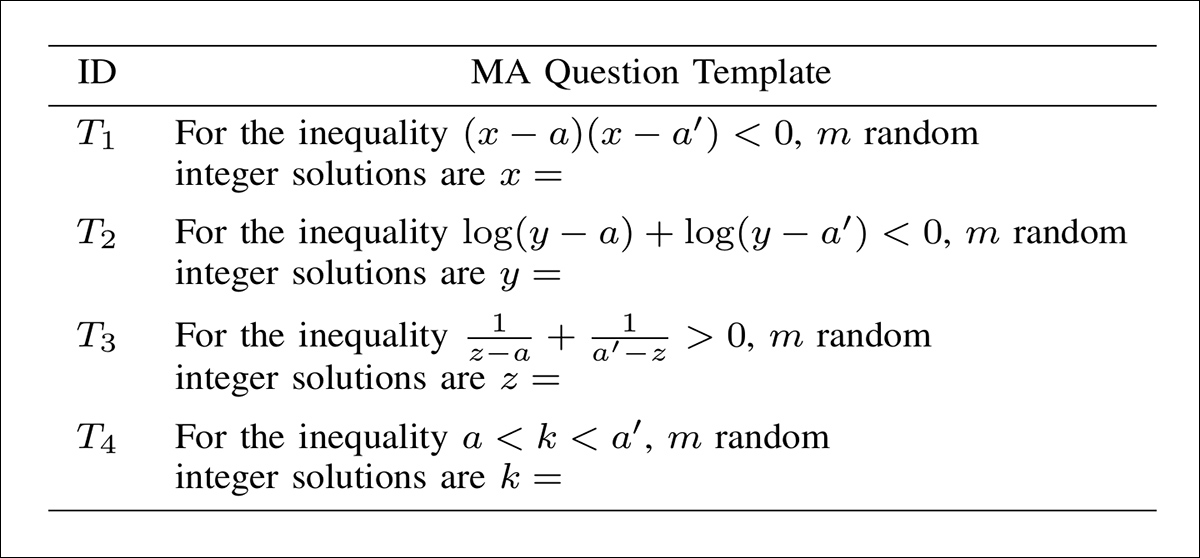

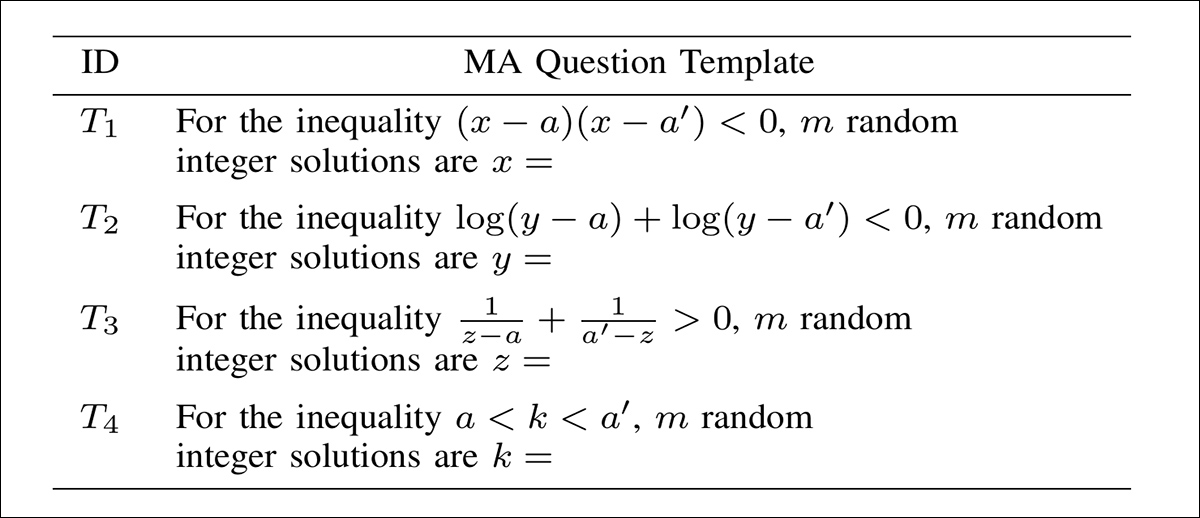

The Generator constructs logically and factually valid math questions with multiple correct answers, using GPT‑4o to diversify templates (as illustrated below), and a pseudo‑random seed to ensure each question is unique. This enables a known watermark to be embedded deterministically via answer permutations, while minimizing overlap between questions, to avoid edit entanglement:

Templates of questions generated by GPT‑4o for watermark embedding, each structured to yield multiple valid integer answers from a seeded inequality.

The Encoder transforms each binary watermark segment into a unique permutation of integers drawn from the solution set of a given math question. Using lexicographical permutation theory, the Encoder maps the decimal value of each watermark chunk to a specific ordered selection of answers, ensuring that the watermark is deterministically embedded in the model’s behavior.

With regards to the editor, the original AlphaEdit model editing method used for watermarking lacks both precision and resilience, with the adjusted model often failing to return the required answers. Any changes it does make are easily broken by pruning or noise.

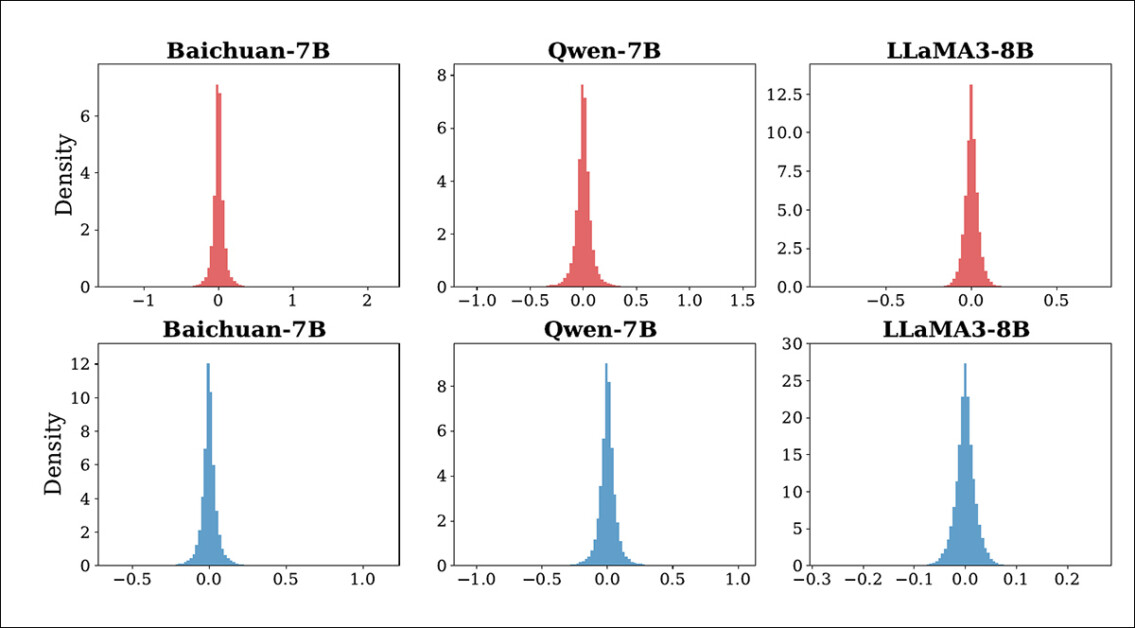

To overcome this, the authors have devised a multi-round editing strategy that gradually adjusts the model weights at a single MLP layer until its responses are sufficiently aligned with the desired answers. To harden the edits against tampering, they Gaussian noise is also injected during training, to simulate attacks:

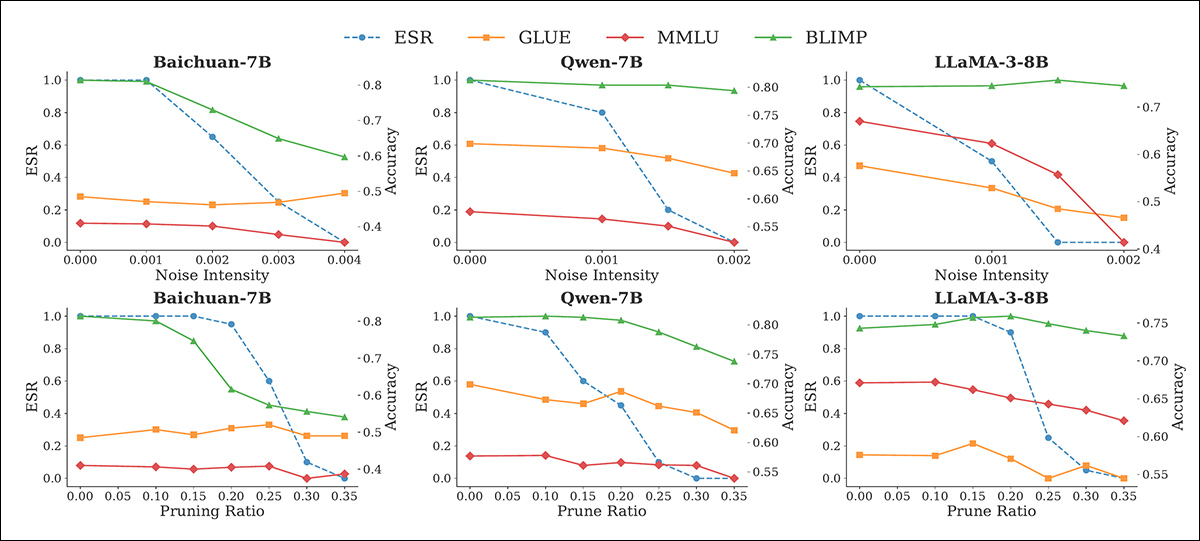

Distribution of changes in K1 for Baichuan-7B, Qwen-7B, and LLaMA3-8B before and after attacks. The top row shows the effect of random noise injection; the bottom row shows the effect of model pruning. All changes stay close to zero, suggesting that the attacks do not significantly disrupt the model’s internal behavior.

A scoring system halts the process once edits are accurate enough, while regularization ensures updates stay stable over multiple rounds.

The Decoder asks the model the same special questions used during watermarking, then reads its answers to infer the hidden ID. Since the pattern of answers follows a secret rule, this ID can be recovered without needing to examine the internals of the model.

Data and Tests

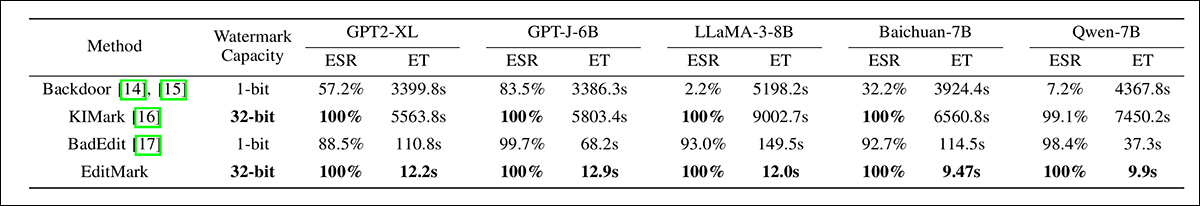

To put EditMark to the test, five LLMs were evaluated: GPT2-X; GPT-J-6B; LLaMA-3-8B; Baichuan-7B; and Qwen-7B. The aforementioned AlphaEdit was used to embed watermarks, while extraction success rate (ESR) and embedding time (ET) were the metrics adopted.

For baselines, the authors chose Model Watermark (backdoor); KIMark; and BadEdit, a framework originally designed for backdoor injection, here adapted to the project’s own purposes.

The authors edited the 15th layer of LLaMA-3-8; the 17th of GPT2-XL and GPT-J-6B; and the 14th of Qwen-7B and Baichuan-7B.

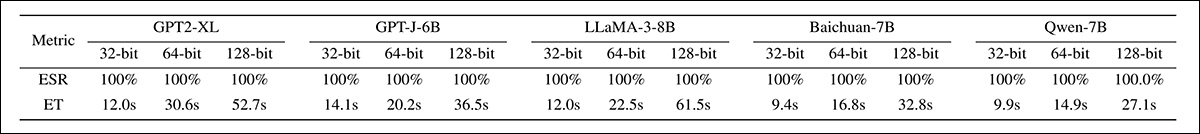

The experiments were conducted on four NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs (24GB of VRAM each), with watermarks of 32-bit, 64-bit, and 128-bit lengths embedded. The question templates used are detailed in the image below:

Templates used to generate multiple-answer (MA) questions for watermarking. Each question is based on a different type of mathematical inequality, with random values inserted for the variables. The model is asked to return a list of integer solutions, with the order of the answers used to encode or decode watermark bits. The four templates cover quadratic, logarithmic, rational, and interval-based forms, and all were generated using GPT-4o.

To reduce the effects of randomness, seeds from 1 to 20 were applied during testing, across different watermark capacities.

Initially the researchers tested for both ESR and time cost in embedding a watermark across the range of LLMs:

Comparison of EditMark against three prior watermarking methods on five large language models. Reported are the extraction success rate (ESR) and embedding time (ET) in seconds. EditMark consistently achieves a 100% success rate while reducing embedding time by several orders of magnitude, outperforming all baselines in both accuracy and efficiency across models of varying size and architecture.

Of these results, the authors state:

‘[EditMark] achieves a 100% ESR and requires less than 20 seconds to embed a 32-bit watermark for all LLMs evaluated. In particular, the average embedding time for Baichuan-7B and Qwen-7B is under 10 seconds, which demonstrates the high efficiency of EditMark.’

For evaluation of a 128-bit watermark, the highest value feasible under such a scheme, EditMark was able to retain a status of ‘indelibility’:

Extraction success rates and embedding times for EditMark across watermark lengths of 32, 64, and 128 bits across five language models. Perfect success rates are maintained in all cases, while embedding time increases with watermark size, but remains under one minute, even at 128 bits.

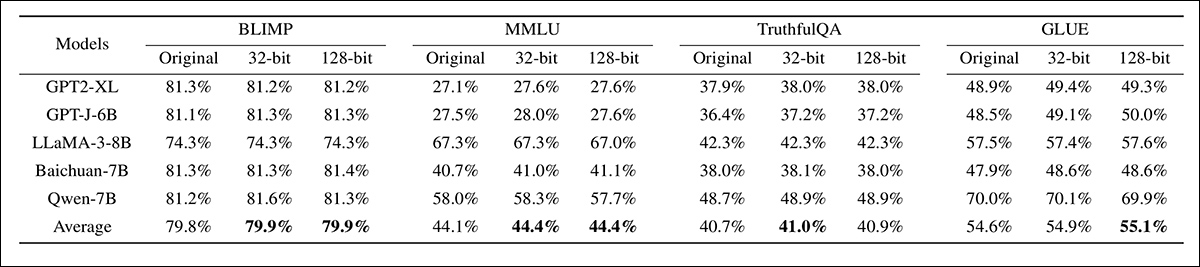

Next the system’s ability to retain watermark fidelity was tested across multiple benchmarks:

Evaluation of watermark fidelity on four benchmarks across five models, comparing unmodified models with models watermarked at 32-bit and 128-bit capacities. Performance remained stable across configurations, with only minor fluctuations in average scores, indicating limited impact on benchmark accuracy from watermark insertion.

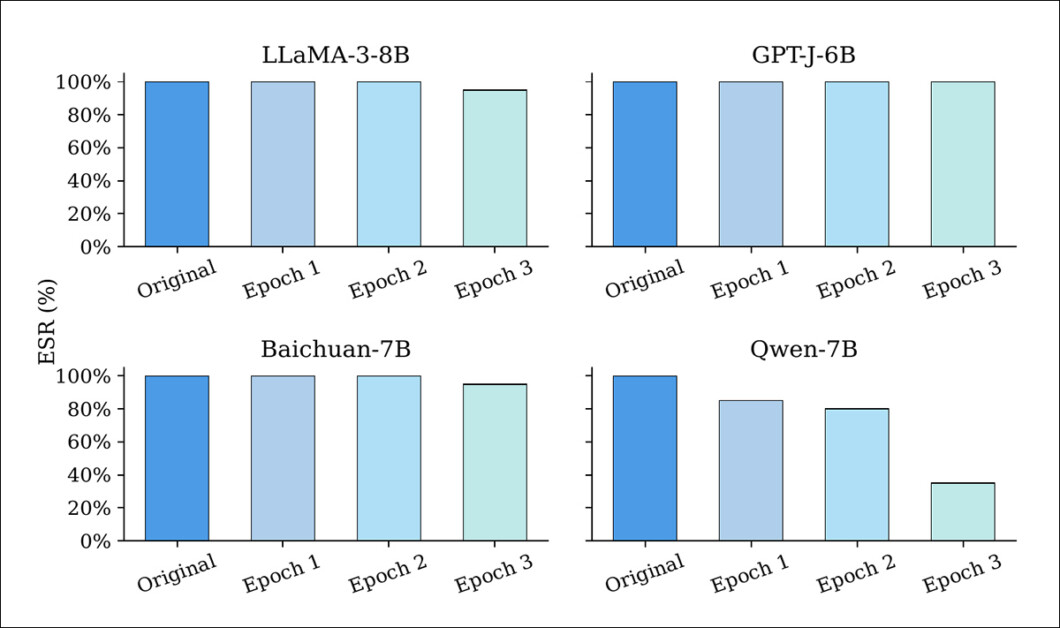

EditMark’s resilience was tested against six common attack strategies. The models were first embedded with 128-bit watermarks using five different seeds. Fine-tuning, as shown in the image below, caused only minor degradation in extraction success rates (ESR) for most models:

Extraction success rate (ESR) of watermarked LLMs before and after fine-tuning for one to three epochs. While most models retain high ESR throughout, Qwen-7B shows a marked decline, suggesting greater vulnerability to parameter updates.

Even after multiple epochs, most models retained ESRs above 90%, indicating that EditMark resists the parameter drift introduced by LoRA-based training.

Quantization attacks reduced model precision, but left most watermarks intact:

Extraction success rate (ESR) of watermarked models before and after quantization using Int‑8 and Int‑4 precision. ESR remained unchanged under Int‑8 quantization across all models, while Int‑4 quantization caused partial degradation, indicating that lower precision can weaken, but not fully remove the watermark.

As we can see in the image above, Int-8 quantization preserved 100% ESR across all models, while Int-4 quantization had a moderate impact on ESR, but introduced unacceptable performance losses.

As the paper notes, this particular scenario suggests limited potential for an attacker, since this results in a hacked but performance-degraded model.

Tests for noise and pruning evaluated four benchmark frameworks: MMLU; BLIMP; TruthfulQA; and GLUE. These attacks led to decreasing ESR as perturbations intensified:

Effect of noise (top row) and pruning (bottom row) attacks on ESR, and benchmark performance of watermarked models. As ESR drops with increasing perturbation, benchmark accuracy also degrades, especially at higher noise intensities and pruning ratios, highlighting the (customary) tension between watermark removal and model utility.

However, these also caused sharp declines in task performance, with Baichuan-7B receiving a 27-31% drop on BLIMP when noise or pruning was applied.

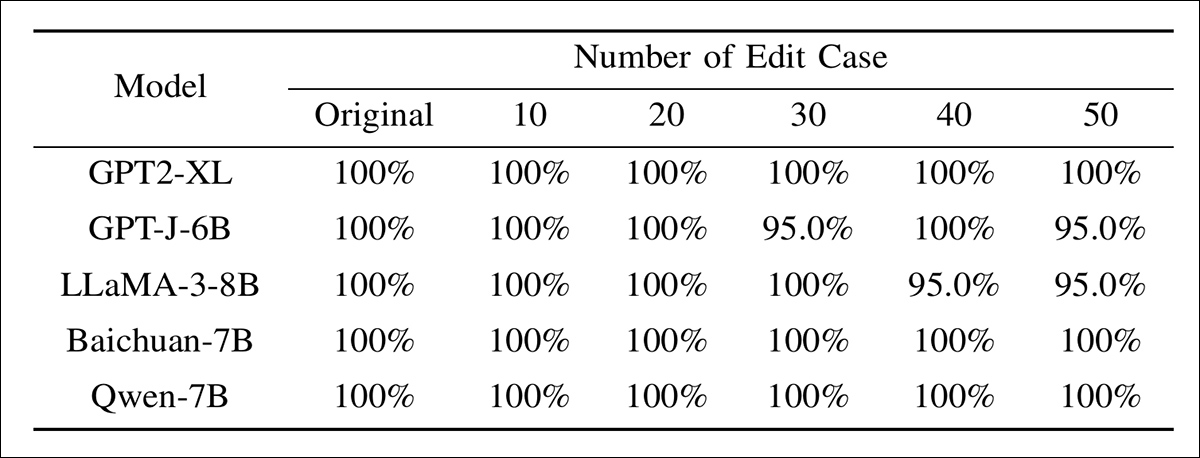

Model editing and adaptive attacks were also evaluated:

Extraction success rate of watermarked models subjected to varying degrees of model editing. Even with up to fifty edits applied to known watermark layers, ESR remains above 95% for all models, indicating that direct parameter modifications have limited effect on watermark removal.

Here EditMark retained over 95% ESR, even when exact embedding layers were targeted.

Conclusion

DRM, secret watermarks, and other security approaches that have enjoyed (limited or partial) success in the pre-AI era are difficult to apply to machine learning systems; the intentionally reductionist nature of the current range of host architectures combines with a lack of appropriate tooling, to make any injected watermarks rather fragile.

It is impressive to see a system aimed at FOSS model distribution, and to see it endure against all scenarios except the most unlikely, in terms of an attacker’s prior knowledge. Nonetheless, the very slight drop in performance that comes with post-training edits, small though it is in these experiments, may give potential adopters cause to pause; not least since retreating to an API-centric model of control obviates such attacks almost entirely.

* This site has contended that ‘open weight’ releases from China do not necessarily qualify as fully FOSS, since data is often withheld, which prevents exact recreation of the training pipeline. Arguably, this topic invites a deeper look at the politics of AI model releases compared across the west and east, which is beyond the scope of this article.

First published Monday, October 27, 2025