Anderson's Angle

Giving Language Models a ‘Truth Dial’

True or chatty: pick one. A new training method lets users tell AI chatbots exactly how ‘factual’ to be, turning accuracy into a dial you can crank up or down.

A new research collaboration between the US and China is offering something that nearly all users of AI chatbots would appreciate: a virtual ‘knob’ that tells the bot whether it should be ‘loquacious’ or ‘truthful’

The system was created by fine-tuning a Mistral-7B model on synthetic data, so that the schema for a ‘truth’ scale could be imprinted on the model. After this revision, the Mistral model is able to control the number of facts in an answer; the higher the ‘truth’ value given by the user, the fewer – but surer – will be the shorter response.

At lower settings, the chatbot’s answer becomes what the paper’s authors call ‘informative’, i.e., it will give a longer answer and contain more facts; but some of the facts may be hallucinated.

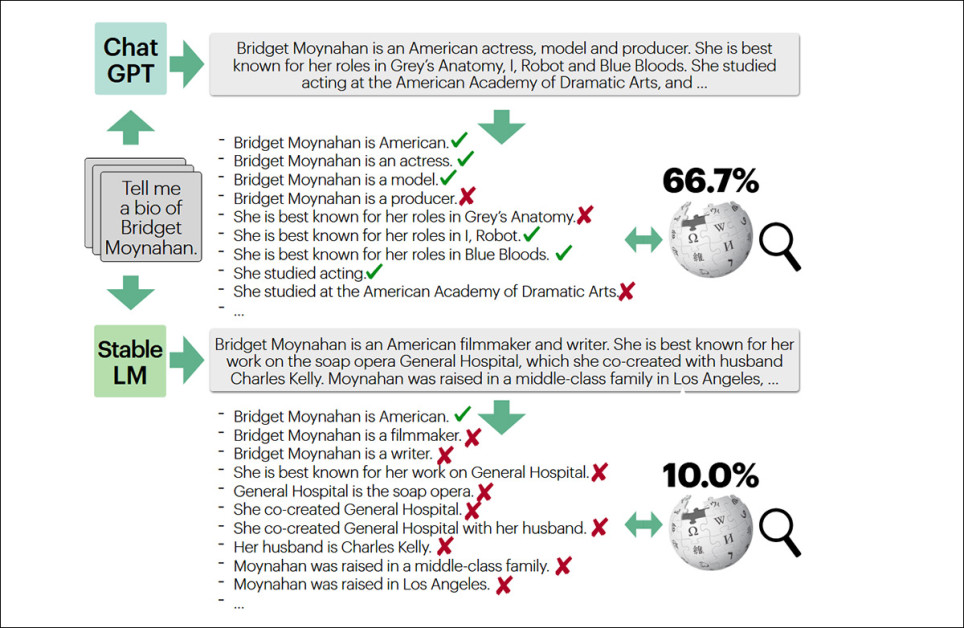

The synthetic data that the system was trained on used Wikipedia as a reference for a test domain: real-life biographical facts about people. Whether or not one thinks Wikipedia should be an authoritative source, the value of the work is in designing any kind of system that can curtail LLMs’ native compulsion to give answers, even when it doesn’t have any answers to give.

An example from the FactScore project which powered the curation of the dataset for the paper we are reviewing here, using Wikipedia as a reference authority for biographical details. Source

The authors note that high-assurance contexts such as medical and legal domains require conservative and reliably factual outputs, whereas many other kinds of users require a more ductile and creative, interpretive kind of output (i.e., discursive writing and academic analysis, among others).

They observe*:

‘[Current] LLMs offer no built-in mechanism to control this trade-off.

‘While users may try to guide the model’s behavior with prompts like “be more factual,” we find that frontier models do not reliably adjust their outputs in response to such prompts on this task.

‘On FactScore, we find off-the-shelf models often fail to satisfy even moderate-to-strict targets. This gap motivates a controllable alternative that lets users request a specific factuality level and have the model adjust its responses accordingly.’

Just the Facts

To understand the paper, and the solutions it is offering, it’s necessary to review one’s own definition of ‘informativeness’. The authors state that the quantification of an informative response equals ‘the amount of supported content in the output, measured as the number of validated atomic statements, normalized by output length’.

Elsewhere the paper states more simply that informativeness is ‘the total number of atomic facts in the output, whether correct or not’.

Further, the researchers note that LLMs’ tendency to range between factual accuracy and subjective guesses is a very human trait, and one documented by diverse scientific studies*:

‘[LLMs’ knowledge] is unevenly reliable: some statements are strongly supported, while others are speculative, outdated, or uncertain. Generation therefore requires deciding how much to say and how cautiously to say it, creating a tension between factual precision and informativeness.

‘Humans make analogous choices: starting with high-reliability facts and adding lower-certainty details only when asked.’

Though experiments were made only on the mid-sized Mistral model, the principles applied should work at a variety of scales and platforms, because it involves a novel quantification of data, as an addition to an LLM’s internal schema; and an amendment of this kind is not architecture-specific.

The new paper is titled Factuality on Demand: Controlling the Factuality-Informativeness Trade-off in Text Generation, and comes from seven researchers across Columbia University, New York University, and NYU Shanghai.

Method and Data

The new approach presented in the paper is dubbed Factuality-Controlled Generation (FCG), and introduces a virtual dial that lets users specify how accurate they want a chatbot’s answer to be. ‘In essence,’ the paper states, ‘FCG improves the model with a controllable “knob” for factuality’.

The model takes both a user question and a desired factuality level, then generates a response that includes only information it considers sufficiently reliable, while still trying to be as detailed as possible within that confidence constraint .

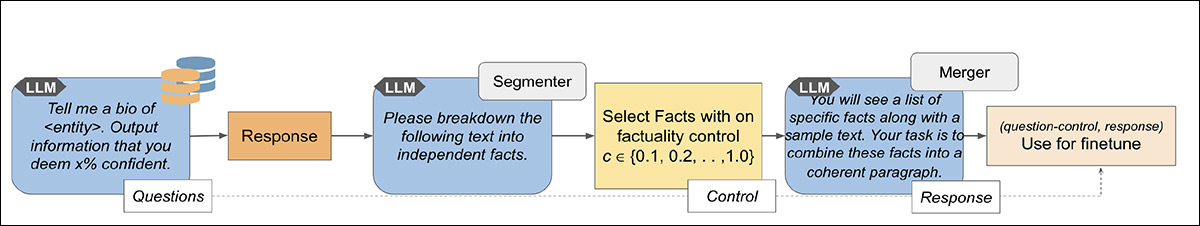

Using the (above-linked) FactScore system, the segmented output from sample queries is evaluated for accuracy, a quality defined as factuality adherence:

Training data pipeline for FCG: a language model generates an initial answer, breaks it into atomic facts, ranks them by confidence, and discards the least reliable until the desired truth level is met. Source

Because no existing dataset matched the requirements of FCG, the authors created a synthetic one by having the GPT-4† language model first generate an unconstrained answer, then strip out the ‘lowest-confidence’ facts, until the response met a given accuracy level.

Prior work suggested that training only on ground-truth data could actually make models less factual, by discouraging them from offering any extra detail at all. Therefore the FCG training examples were minimally edited, preserving the model’s own phrasing and rhythm, while paring down just enough to meet the required target confidence.

By applying this editing process across a range of target confidence levels, from 10% to a strict threshold of 100%, a synthetic dataset was created in which each question was paired with multiple filtered responses.

In each version, only those facts judged by the model to be sufficiently reliable to meet the requested level of factuality were retained; these examples were then used as training data for supervised fine-tuning.

The final dataset consisted of 3,302 (question, control, response) triples for training, and 396 for validation, built from 500 entities split into 450 for training and 50 for development. An additional 183 distinct entities were used for testing.

Training and Tests

The authors fine-tuned the Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 LLM model at various learning rates (3e-6, 1e-5, 3e-5) to arrive at the optimal (unstated) LR, for 30 epochs, at a batch size of 256 (n.b. the training hardware is not specified).

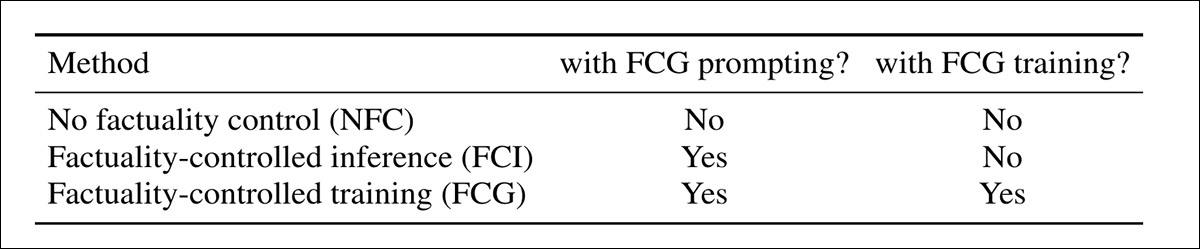

FCG was tested against two baselines. The first was No Factuality Control (NFC), where the model was simply prompted with a request such as Tell me a bio of X, with no mention of accuracy or confidence. This version reflects the default behavior of an LLM, without any mechanism for filtering or constraint.

The second method, called Factuality-Controlled Inference (FCI), used the same confidence-level prompts without any fine-tuning. For instance, the model might be prompted with ‘Output information you deem 90% confident’. In this case, the instruction resembled those used in training, but the model had no prior exposure to such constraints:

Comparison of the three tested approaches: the baseline with no control; a version using factuality prompts without training; and the fine-tuned model that learned to follow accuracy settings through exposure to filtered data.

Initially a test was made for factuality adherence:

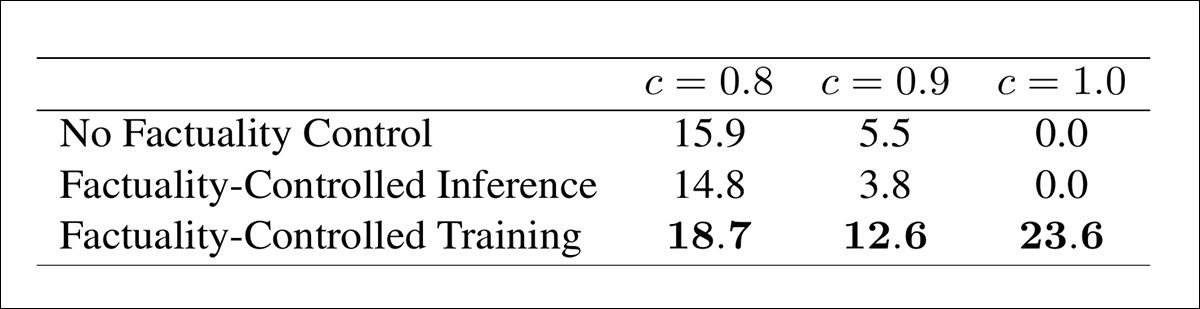

Performance at three target confidence levels. Only the fully trained model was able to produce any fully factual outputs, and it outperformed both baselines across the board, particularly at higher thresholds.

When tested against factuality thresholds of 80%, 90%, and 100%, only the fine-tuned model was able to consistently meet the targets. Surprisingly, simply adding confidence instructions, without training the model to follow them, did not help. In some cases, it made things worse; for instance, only 3.8% of outputs from the prompted model met the 90% threshold, compared to 5.5% from the version with no instruction at all:

This suggests, the authors assert, that the base Mistral-7B model was unable to interpret prompts like ‘be 90% confident’ in a useful way, and that the extra instruction may even have disrupted its usual output.

By contrast, the trained model responded reliably to control signals, producing 18.7% compliant outputs at 80%, 12.6% at 90%, and 23.6% at 100%; and it proved the only method able to generate any fully factual answers:

‘These improvements indicate that the ability to control factuality can indeed be instilled via supervised training. The FCG model has learned to adjust its content and only include facts that it is sufficiently confident in, whereas the off-the-shelf model could not effectively utilize the control signal on its own.’

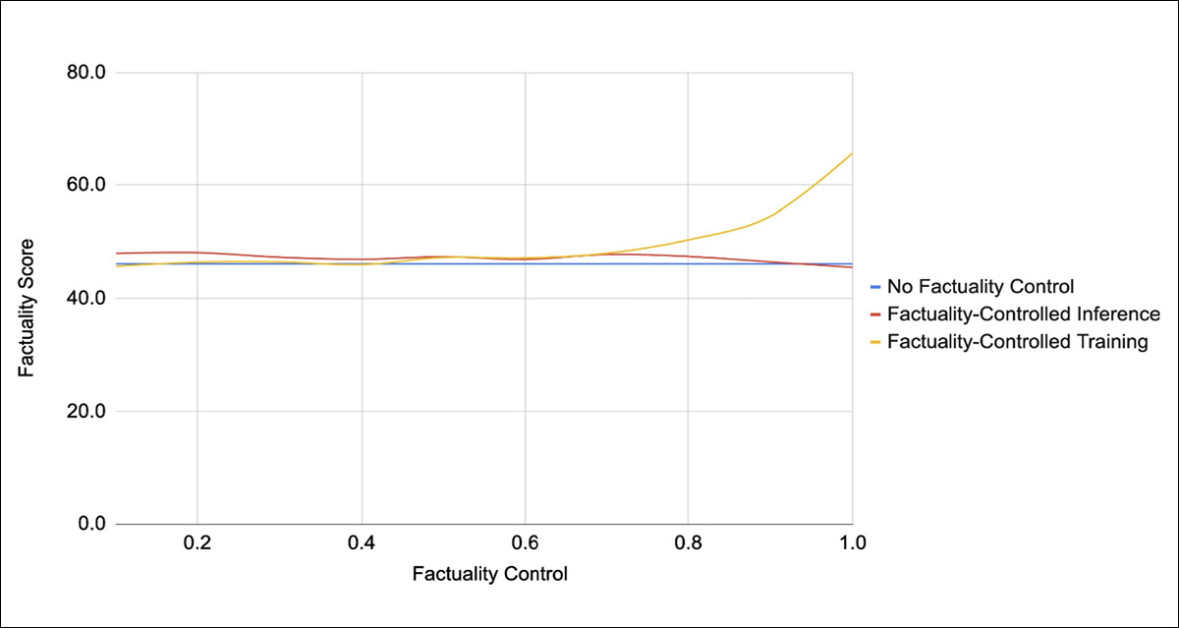

In a separate test designed to confirm that the model had actually learned to interpret the control signal, the researchers checked whether the average factuality of responses rose as higher truth settings were requested.

No such pattern emerged prior to training, but afterward, the results revealed a steady upward trend, with higher requested confidence producing correspondingly more accurate responses:

As the target truth setting rose, the fine-tuned model produced increasingly factual outputs in response, with the baseline models demonstrating no consistent change across the same range.

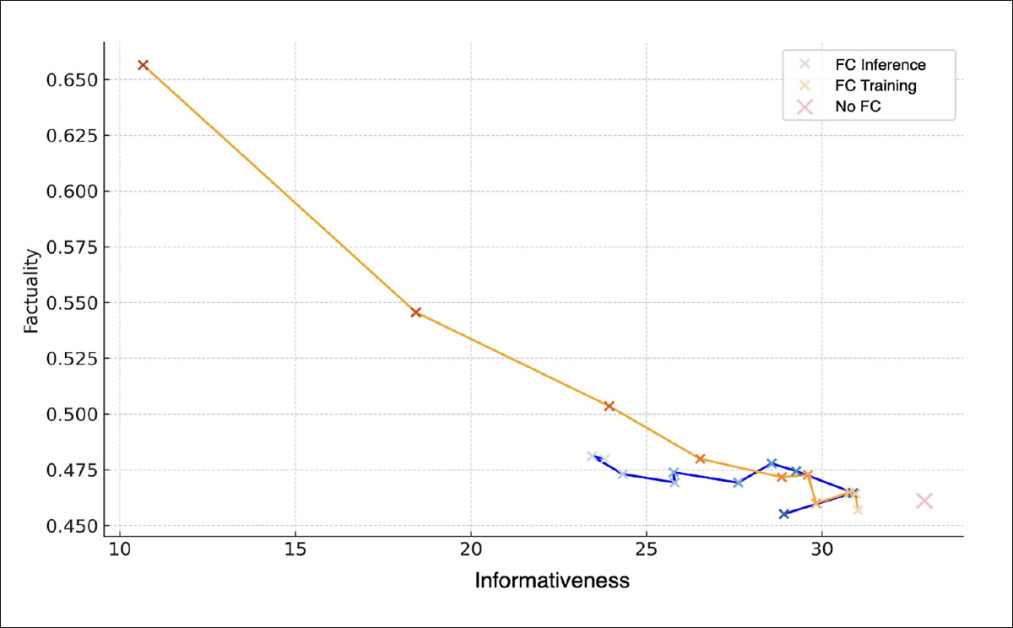

The trade-off between truthfulness and ‘richness’ was also examined. Outputs were scored not only for accuracy but for how much verified information remained under increasingly strict factuality requirements. As shown in the graph below, the FCG model was found to outperform both the inference-only baseline and the unconstrained model at most levels:

A graph representing the factuality vs. informativeness trade-off across three methods. The fine-tuned model was found to offer a better balance between truth and detail than either baseline. At comparable accuracy levels, more factual content was preserved, and at the highest setting, it remained the only method able to produce fully verified responses that were not empty.

At a target accuracy of around 90%, more facts were retained by FCG than by any other method, and across the full range of confidence settings, no baseline produced consistently better results.

The difference was most striking at the strictest setting, where FCG continued to produce nonzero informativeness, while the baseline with prompts alone was forced to remove everything. In those cases, even a single low-confidence statement caused the entire response to be discarded.

By contrast, the trained model was able to reshape its output to preserve only facts it considered fully reliable, avoiding the collapse into silence that affected the others.

Factuality was directly constrained by the control setting, while informativeness was optimized by letting the model include as much reliable content as possible. At higher settings, only trusted statements were kept; at lower ones, more speculative details were allowed, increasing length but reducing accuracy.

The authors conclude:

‘[When] a high factuality constraint is in place, the model prioritizes factually verifiable statements while still including as much relevant information as possible. Conversely, the model has the freedom to incorporate a broader range of details, including some that are less verifiable or more speculative, resulting in higher informativeness (more facts mentioned) at the cost of some accuracy.

‘This behavior aligns with our design of the training data: because we always removed the minimum necessary facts, the model learned “if you must be x% factual, drop the least-certain details but keep everything else.” ‘

The paper closes out with the hope that the new methodology will be tried with larger-scale models, and applied to more complex tasks, among other possible future extensions of the work.

Conclusion

The solution offered here addresses one of the most severe and oft-noted bugbears of even the latest generation of Large Language Models – their tendency to favor loquacity over accuracy, apparently just to ‘keep the conversation going’, and to confidently present either outdated or fully-hallucinated information as factual.

For ChatGPT users, any confident answer not preceded by the brief appearance of a ‘searching web’ widget will either come from the confines of the model’s knowledge cutoff date, or else could as well be hallucination as fact.

However, web searches increase latency and the LLM host’s running costs, and, as any user knows, are run selectively; or at the user’s request; or as a ‘special setting’ that may incur extra token charges.

Nonetheless, these kinds of internal economics can have a critical effect on LLM queries in certain domains, or for certain types of query. Any method that can impose a schema related to accuracy of output is welcome research indeed.

* My conversion of the authors’ inline citation to hyperlinks.

† Full version number not given.

First published Friday, February 6, 2026. Amended in the following five minutes for a word repetition