Anderson's Angle

AI-Generated Writing Never ‘Tires’, and Thus Reveals Itself

ChatGPT-style AI gives itself away by increasing in consistency, while human writing remains erratic throughout.

The limited context window of most consumer-facing Large Language Models (LLMs) is one of the factors that can make them forget or incorrectly recall earlier parts of users’ conversations – errors of recall which can gradually turn the output into total nonsense – or, worse, deceptively coherent-looking text that contains subtle errors.

Since these circumstances lead to hallucinations, and since hallucinations are still the biggest obstacle to AI’s total market advance, much research effort has been expended in creating generative AI systems that can create longer but much more consistent tranches of text.

In fact, so much progress is being made that recognizing long-form AI content (i.e., content purely generated by AI, with – presumably – minimal or zero human aftercare) is considered to be a growing problem.

Busting an AI Filibuster

Nonetheless, recent empirical studies contend that the more output that AI text generators produce in one blast, the easier it is to determine whether or not that text was human-written; but the accepted wisdom in regard to this detection ‘anchor’ has assumed that AI can be discerned because whatever it is doing differently from humans, it gets a chance to do more often in longer tracts.

No assumptions are made about the distribution of these ‘tells’ in the text itself.

To challenge this, and expand upon the problem, an interesting recent research study from China offers a novel method of distinguishing the new breed of long-form AI content generators from real human authors. The researchers behind the work claim that the token-upon-token nature by which AI text is generated means that it becomes more consistent with greater length, whereas people’s own eccentricities do not diminish with length.

In this way, the authors suggest that their insight offers a potential new metric for AI-text detection systems*:

‘AI-generated tokens in the latter portion of text exhibit smaller and more stable probability fluctuations as the model’s predictions become increasingly consistent as context accumulates.

‘We term this pattern Late-Stage Volatility Decay. This phenomenon reflects the inherent behavior of autoregressive generation: as more context becomes available, the model’s prediction distribution sharpens, leading to reduced variability in token-level statistics.

‘Human writing, by contrast, continues to introduce unexpected lexical choices and maintains higher volatility throughout.’

To capture this strange ‘smoothness’ that accumulates in AI text toward the end, the researchers define two simple features: the first measures how much the writing’s statistical behavior ‘jumps around’ between tokens; the second checks how stable things stay over short stretches of text.

Both are computed only from the second half of the output, where AI becomes noticeably more regular and human writing does not. The authors note that while these signals work well on their own, they are even more effective when combined with older detection methods that scan for broader patterns. They note also that this approach performs best on longer texts, where the contrast can become more evident.

The new paper offers a methodology for testing ‘AI-ness’ via second-half temporal feature analysis, requiring no additional training or fine-tuning, or privileged model access.

The new work is titled When AI Settles Down: Late-Stage Stability as a Signature of AI-Generated Text Detection, and comes from four authors at Westlake University in Hangzhou.

Method

To capture the growing smoothness in AI-generated text, the researchers designed two measurements that focus only on the second half of a passage. These rely on log-probability scores from a standard language model and require no fine-tuning, retraining, or extra samples:

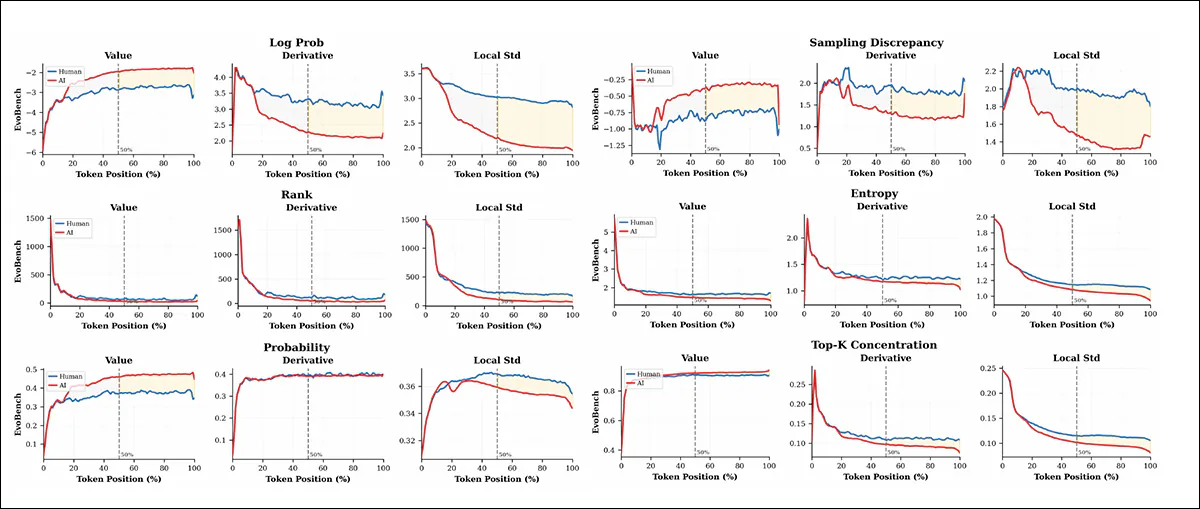

From the new paper – each row shows the behavior of a base metric from EvoBench across the token sequence: raw value (left), absolute derivative (center), and local standard deviation (right). Human and AI lines are shown in blue and red. Most divergence appears in the second half of the text, especially for Log Probability and Sampling Discrepancy, which show rising separation and smoother AI output. Entropy and Top-K Concentration show little change over time. Source

The first measure, called Derivative Dispersion (DD), tracks how sharply the model’s confidence changes from one word to the next. AI text tends to settle into a rhythm, so these changes become smaller and more predictable in the second half. By contrast, human writing stays ‘uneven’.

The second measure, Local Volatility (LV), looks at how much the model’s confidence ‘jumps around’ within a small window of text. Again, AI tends to grow steadier over time, while human choices remain more surprising and less consistent:

AI text becomes smoother as it goes, while human writing remains uneven. These graphs track how the model’s confidence shifts over the course of a passage, reflecting both the sharpness of change between successive words and the amount of variation within local stretches of text. In both respects, the decline is much steeper in machine-generated output, with the contrast becoming especially clear after the midpoint. The yellow boxes highlight this widening gap in the second half, where AI writing reaches up to 32% greater stability than human writing.

Once again, both metrics are calculated only from the latter half of the text, where the difference between human and machine writing is most evident. These are then incorporated into a single value called the Temporal Stability Detection (TSD) score – which is prone to rise as the writing becomes ‘smoother’ (and therefore more likely to be AI-generated). A simple threshold is then used to decide whether a given passage is probably written by a machine.

Because these features focus on when a pattern emerges, rather than just what that pattern looks like, they are complemented by older methods that search for statistical oddities across the whole passage. Adding the TSD score to the output of the late 2024 offering Fast‑DetectGPT (also in collaboration with Westlake) offers an additional improvement in results (especially for long-form content where the late-stage smoothing effect is strongest).

Data and Tests

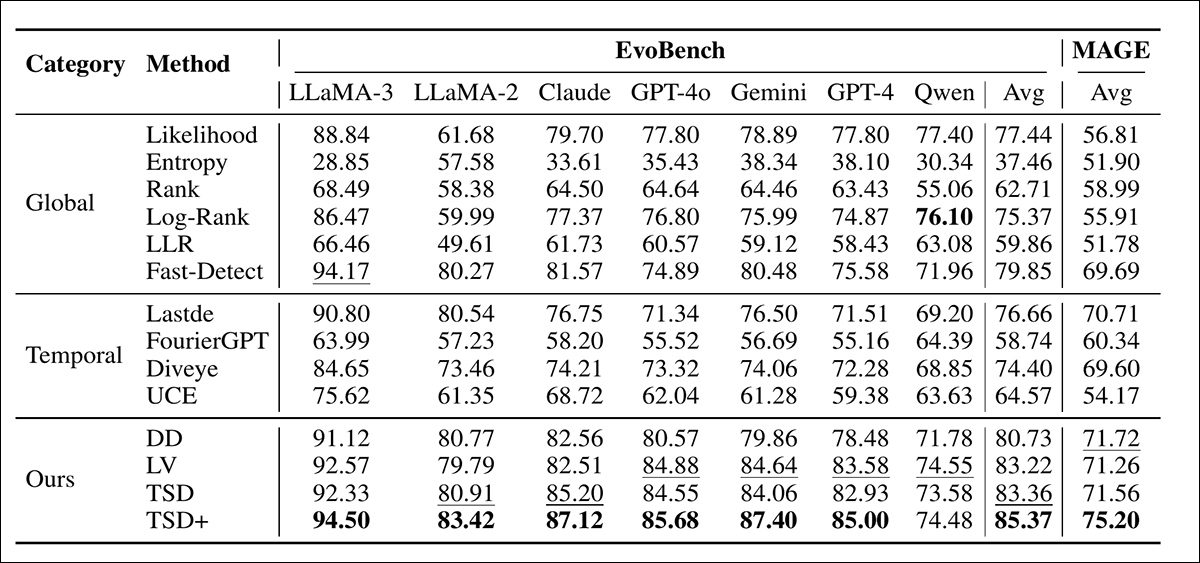

The authors conducted tests on two related benchmark datasets: EvoBench contains 32,000 human/AI text pairs generated across seven model families, including GPT-4; GPT-4o; Claude; Google Gemini; LLaMA-3; and Qwen, with a total of 29 model versions featured.

The other framework was MAGE, which offers 30,000 test pairs across eight model families, including (but not limited to) the GPT series from OpenAI, and the LLaMA, OPT, and FLAN-T5 families.

Contenders

The new method was tested against a range of zero-shot detectors using the same surrogate model. Likelihood, Entropy, Rank, and Log-Rank (DetectGPT) measured token-level statistics over the full passage; LLR (DetectLLM) applied normalization to allow direct comparison across models; and Fast-Detect estimated local curvature through sampling-based perturbations.

Lastde analyzed discriminative subsequences in the probability signal, while FourierGPT operated in the frequency domain. Diveye captured shifts in ‘surprisal’ diversity across the sequence.

Finally, UCE evaluated the uncertainty profile of token predictions, to identify unnatural confidence patterns.

Implementation and Outcomes

All detection methods were run using Llama-3-8B-Instruct as a shared surrogate model, with input sequences limited to 512 tokens. Temporal features were extracted only from the second half of each passage, using a sliding window of 20 tokens to measure volatility. A fused version of the method, called TSD+, combined the proposed signal with Fast-DetectGPT.

Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) was the primary evaluation metric†:

Diverse performance among the various tested methods against AI-generated text. Detection accuracy is shown across two benchmarks: EvoBench, which covers multiple high-profile LLMs, and MAGE, a complementary dataset. Metrics are grouped by method type: global statistics, temporal features, and proposed variants. Average AUROC scores are given in the final columns. Results from the authors’ method variants consistently outperform prior baselines, with TSD+ yielding the highest scores in nearly every model setting.

Of these initial results, the authors state:

‘Our simple temporal features achieve state-of-the-art performance among standalone methods, with TSD attaining 83.36% on EvoBench and 71.56% on MAGE, outperforming all baselines including Fast-DetectGPT.

‘This is notable given our method’s simplicity: we compute only second-order statistics from the second half of sequences, without perturbation sampling or frequency-domain transformations.’

The new method worked especially well on newer AI models such as GPT-4 and GPT-4o, identifying AI-written text more accurately than the nearest leading detector, with a performance gap of up to 9.66%. Though newer advanced models produce less obviously ‘consistent’ text, which hides some signs of automation, certain subtle timing patterns are still evident near the end.

Competing approaches that focus on broad structural features failed to capture these late-stage patterns. By integrating a global detector, the hybrid system apparently recovers these missed signals, and improved performance, particularly on benchmarks where shorter AI outputs can weaken temporal cues.

Conclusion

One aspect not directly addressed in the new work is the tendency of human writers to iterate their work through drafting and various layers of oversight – sometimes including external oversight, such as the input of editors and proof-readers, as well as possible suggested changes from legal departments, depending on the context.

The multiple stakeholders involved in documents as simple as a well- buried newspaper article can all but obliterate the eccentricities that the new proposed system is keying on, and in effect amounts to a kind of ‘analog version’ of an AI-aided drafting process.

Additionally, the systems under study have themselves trained on such works, and – as training data is increasingly ranked in authority at training time – the most ‘weighted’ or regarded sources may be the least ‘natural’; at least, compared to someone quickly composing a casual email to a colleague, rather than assembling a yearly report for an AGM.

A further and contrasting consideration is that text content to which multiple people have contributed can also be among the most fragmented, flawed and repetitive pieces of prose to enter a dataset, since they often will not have had the benefit of a final unifying voice, leaving the piecemeal nature of their development evident in the prose.

* Authors’ original text-styling reproduced from the paper; not my emphases.

† The authors state ‘primary’, while listing no other evaluation metrics.

First published Monday, January 26, 2026