Anderson's Angle

AI Could Help You Reach a Real Person Faster

New research shows that open source ChatGPT-style AI setups can potentially route callers to the right person in a call center using natural language, without following infuriating menu choices that are different every week, seeming deliberately obstructive.

Trying to get through to a real person at a call center can be a frustrating experience, due to the need to navigate multiple-choice options at a slow pace – often without certainty as to which of the choices suit your case. If none of them do, experienced users tend to adopt tricks and workarounds to gain access to a human adviser of some kind, and to get out of ‘option hell’. Many of us will recognize this as a more or less ‘combative’ and user-hostile experience.

Unsurprisingly, call centers are in the front line for augmentation or replacement by AI systems; and, despite a circumspect approach being urged from some quarters, call center AI automation remains low-hanging fruit for tech headlines, and for the prospect of AI-based innovation that can offer unusually early early ROI.

Closed Shop

But there are some areas where open source principles and freely-available data are rarely applied or available, and this is one of them. It makes sense: any company interested in automating their customer response systems will have limited or zero interest in sharing the data that powers their hard-won insights, their methodologies, or their corporate IP.

For one thing, sharing these resources would cost them an edge with competitors; more importantly, given how prone AI-in-the-loop systems are to disclose privileged information, it’s legally risky.

This has led to a number of well-invested players developing AI-aided call center response systems independent of each other (presumably with some inevitable redundancy of effort); and to a proliferation of B2B startups and established players seeking to cater to the growing demand for AI-driven customer response capabilities.

A PolyAI voice assistant opens a customer service call for fictional company ‘Augusta Lawn Care’, drawing on large quantities of training conversations to automate responses through existing call center infrastructure. Source

Additionally, the race to remove the frustration of navigating a call-center maze has proved a spur to research efforts – though most such publications tend to occur away from Arxiv and other open research publication networks, in keeping with the generally clandestine nature of Interactive Voice Response (IVR) development.

Instead, research, data and business intelligence related to AI automation of customer response systems are all jealously guarded, with very few open source options available – even if the use of FOSS systems and data offered a legally sound option, which is doubtful.

Local Call

With this in mind, it’s refreshing to see a new paper from Colombia attempting to break IVR out of its corporate vault, at least a little. The new work, a succinct entry titled Beyond IVR Touch-Tones: Customer Intent Routing using LLMs, comes from a researcher at Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas at Bogotá, and claims to be the first non-closed project to use Large Language Models (LLMs) to generate a working schema for a Customer Intent Routing (CIR) system.

Instead of trying to gain access to real-world call data or proprietary menu trees, the new project generates all components from scratch using three AI models: one to invent a realistic call center menu; another to simulate hundreds of caller complaints; and a third to act as the chatbot, trying to route those complaints to the right destination.

The result is a fully synthetic but convincing test-bed, featuring a fictional telecom company, along with 920 distinct user queries, allowing the experiment to sidestep legal risks while probing how well current AI can interpret vague, messy speech, and still connect the caller to the right person.

Tests indicate that the scheme’s system can match free-form caller complaints to the correct call center destination with up to 89.13% accuracy, especially when given ‘flattened’ menu options instead of verbose descriptions (more of this later).

The study also found that when callers used more casual or varied language, the AI erred more; but that some of those mistakes happened not because the AI misunderstood, but because the phone menu itself was confusing.

![Examples of customer interactions, shared as part of the new project. [Source] https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Beyond_IVR_Touch-Tones_Customer_Intent_Routing_using_LLMs/30118690](https://www.unite.ai/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/figshare-examples-data.jpg)

Examples of customer interactions, shared as part of the new project. Source

Data for the project has been made publicly available.

Method

The first model in the tripartite approach creates a detailed phone menu for a fictitious telecom company; the second generates unique caller messages – some simple, others rephrased or made more casual – to simulate how people actually talk when calling for help. Regarding this, 920 examples were generated for the project.

The third model was given the task of connecting each caller to the correct department, based only on the message, and a version of the menu. This schema allowed the experiment to be fully repeatable, while sidestepping the need for real call data or exposing customer information:

![The three systems chosen for the tripartite approach. [Source] https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.21715](https://www.unite.ai/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/table-1-5.jpg)

The three systems chosen for the tripartite approach. Source

The three models used, respectively, were gpt-3.5-turbo; gpt-4o-mini; and gpt-4.1-mini.

To simulate a convincing customer service environment, it was necessary to synthesize a complex phone menu from scratch. Due to the scarcity of relevant datasets, the gpt-3.5-turbo model was prompted to generate a full, multi-branch structure for a fictional telecom provider.

Each branch was configured to represent service areas such as billing, technical support, account management, and new services, with realistic sub-options and varying depth across the tree. From this artificial menu, two versions were created for later testing: one as a plain text hierarchy, to mimic how a human might read the entire menu; and another as a list of endpoints, each with its own sequence of button presses.

This allowed the system to be tested both on a detailed and on a ‘stripped-down’ version of the routing challenge:

Two versions of the phone menu were provided to the AI: a detailed text hierarchy, and a simplified list of direct menu options, to compare how well each format supported routing callers to the right place.

To create the caller messages needed for testing, a second language model was used to produce a set of original complaints or requests, with ten unique examples made for each menu endpoint.

Each of these was then expanded into several reworded versions, to mimic the range of ways that real callers might phrase their problems, and introduced changes in length, tone, and even minor errors or ‘filler’ language.

The 920 caller messages generated at the outset were designed both to test the system’s precision and to simulate the unpredictability of real-world speech.

The third stage tested how accurately the final model could map each caller message to the right menu destination, based on the two different ways of presenting the IVR system (see image above).

In the first version, the AI was given a full, descriptive outline of the phone tree, with every branch and sub-option laid out in text form. In the second, it saw only a list of final destinations, each tied to a button sequence.

The goal was to see whether a stripped-down version of the menu would make it easier for the model to decide where each call should go. In both cases, the system received one message at a time, and was asked to return only the path, with no additional words or explanation, to facilitate automatic scoring.

Isolation

To avoid contaminating the test results, the experiment kept each model isolated from the others: the phone menu was drafted by the first model, but then finalized manually, so that it remained unfamiliar to the other systems.

The caller messages were then generated separately by gpt-4o-mini, using only the names of the endpoints, and with no access to the menu structure. Finally, gpt-4.1-mini, which handled the routing, saw only the text of the menu and the incoming messages, and had no involvement in creating either.

Metrics

To measure how well the routing system performed, two standard metrics were used: accuracy was defined as the percentage of cases where the model returned the exact correct path (such as 1‑2‑3). To isolate the location of errors, confusion matrices were also generated*, showing how often each path was confused with others. The evaluations were executed in Python using the pandas and scikit-learn libraries.

Results

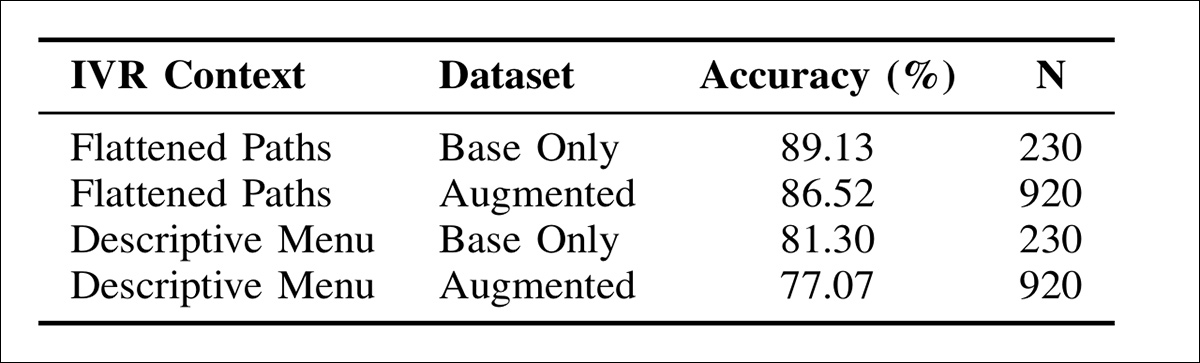

In tests, the model’s accuracy depended strongly on how the phone menu was presented: when given the flattened list of menu paths, the system reached 89.13% accuracy on the simpler dataset, compared with 81.30% when using the full descriptive version of the menu:

Routing accuracy for the third (LLM3) model, across different prompt formats and dataset types, indicating that flattened menu paths consistently outperformed hierarchical descriptions, and that accuracy declined slightly when inputs were augmented with paraphrased or informal language.

This pattern held for the larger, linguistically varied dataset as well, where the flattened version again performed better, scoring 86.52% against 77.07% for the descriptive format.

These results, the paper notes, suggest that simpler, list-based prompts helped the model match queries more reliably than long hierarchical descriptions.

Accuracy also dropped slightly when paraphrased and informal versions of caller messages were introduced, indicating that greater variety improved realism, but also made classification harder.

The paper concludes:

‘Our results show that LLMs route intents more accurately when given flattened IVR paths (up to 89.13) than verbose menu descriptions (as low as 77.07%), suggesting that concise, structured prompts reduce noise and align better with the routing task.

‘This supports the principle that clarity and brevity enhance LLM performance in classification settings.

‘Importantly, transforming menus into flattened paths is a simple, automatable process for real-world use.’

Conclusion

It is refreshing to see at least some open work occurring in one of the most cloistered and exclusionary strands of research in the literature. What remains to be seen is whether ‘framing’ architectures which contextualize LLMs will be needed in the future, or whether the model will only need access to (locally-available) business intelligence, obviating the need for the company to share data with third-party providers.

Ultimately, the broader design principles at work here seem likely to be adopted naturally by future AI systems, even in domains beyond customer service, without requiring deliberate alignment to that use=case.

* Please refer to the source paper for these.

First published Wednesday, October 29, 2025