Anderson's Angle

AI Chatbots Lean Left When Voting on Real Laws

In the first study of its kind that uses high-scale real-world data, ChatGPT and other Large Language Models were tested on thousands of real parliamentary votes, and repeatedly aligned with left and center-left parties, while showing weaker alignment with conservative ones across three countries.

In a new academic collaboration between the Netherlands and Norway, ChatGPT-style Large Language Models (LLMs) – including ChatGPT itself – were asked to vote on thousands of actual parliamentary motions that had already been decided by human lawmakers in three countries.

When compared to the recorded votes of real parties, and mapped onto a standard political scale, the pattern that emerged placed the AIs consistently closer to progressive and center‑left parties, and farther from conservative ones.

The paper states:

‘Our findings reveal consistent centre-left and progressive tendencies across models, together with systematic negative bias toward right-conservative parties, and show that these patterns remain stable under paraphrased prompts.’

Most prior studies, such as Assessing Political Bias in Large Language Models, and those reviewed in Identifying Political Bias in AI, use small curated quizzes such as political compass tests, or policy questionnaires, to probe an AI’s ideology. Tests of this nature typically involve fewer than 100 statements, hand-picked by researchers, and can be vulnerable to rewording effects that can reverse a model’s responses.

By contrast, the new study uses thousands of real parliamentary motions from three countries – the Netherlands, Norway and Spain – using recorded votes from known political parties.

Rather than interpreting short statements, each Large Language Model (LLM) tested was asked to vote on actual legislative proposals. Its votes were then matched quantitatively against real-world party behavior, and projected into a standard ideological space, a Chapel Hill expert survey (CHES), a methodology often used by political scientists to compare party positions.

This grounds the analysis in large-scale, real-world legislative activity instead of abstract policy statements, and enables finer-grained, cross-national comparisons. It also emphasizes the deleterious effect of entity bias (how the model’s response changes when a party name is mentioned, even when the motion remains unchanged), illuminating a second layer of bias detection not present in prior work.

Most studies on LLM biases have centered on social fairness and gender, among other similar topics that have become somewhat deprioritized over the last political year; until recently, studies of political bias in LLMs have been rarer and less meticulously-tooled and conceived.

The new work is titled Uncovering Political Bias in Large Language Models using Parliamentary Voting Records, and comes from seven researchers across Vrije Universiteit at Amsterdam, and the University of Oslo.

Method and Data

The central proposition of the new project is to observe the political tendencies of a variety of language models, by asking them to vote on historical legislation (i.e., laws that were already passed or rejected in real life, across the three countries studied), and using the CHES methodology to characterize the political color of the LLMs’ responses.

To this end, the researchers created three datasets: PoliBiasNL, to cover 15 parties in the Dutch second chamber (featuring 2,701 motions); PoliBiasNO, to cover nine parties the Norwegian Storting (featuring 10,584 motions); and PoliBiasES, to cover ten parties in the Spanish parliament (featuring 2,480 motions – and the only dataset to include abstention votes, which are permitted in Spain).

Each motion was stripped to its operative clauses to minimize framing effects, and party positions encoded as 1 to indicate support, or –1 to indicate opposition (and, in the Spanish dataset, 0 to reflect abstentions). Consistent votes from merged parties were treated as a single bloc, while for new parties such as New Social Contract (NSC), past votes by their leaders were used to infer earlier positions.

A diverse array of experiments were devised for a raft of LLMs, tested either on local GPUs or via API, as necessary. Models tested were Mistral-7B; Falcon3-7B; Gemma2-9B; Deepseek-7B; GPT-3.5 Turbo; GPT-4o mini; Llama2-7B; and Llama3-8B. Language-specific LLMs were also tested, these being NorskGPT for the Norwegian dataset, and Aguila-7B for the Spanish collection.

Tests

Experiments carried out for the project were run on an unspecified number of NVIDIA A4000 GPUs, each with 16GB of VRAM.

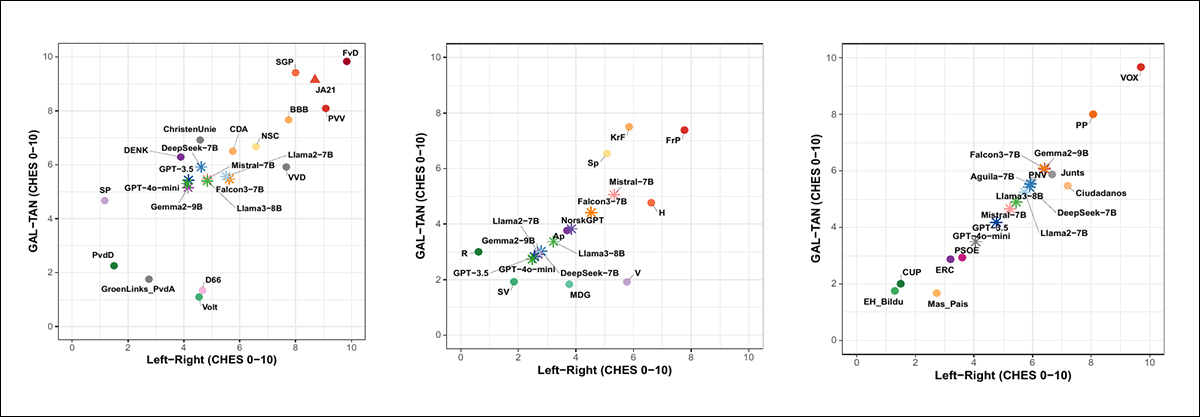

To compare model behavior with real-world political ideologies, the researchers projected each LLM into the same two-dimensional ideological space used for political parties, based on the aforementioned CHES framework.

The CHES system defines two axes: one for economic views (left vs right) and another for socio-cultural values (GAL-TAN, or Green-Alternative-Libertarian vs Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist).

Because both models and political parties had cast votes on the same motions, the researchers treated this as a supervised learning task, training a Partial Least Squares regression model to map each party’s voting record to its known CHES coordinates.

This model was then applied to the LLMs’ voting patterns to estimate their positions in the same space. Since the LLMs were never part of the training data, their coordinates would therefore offer a direct comparison based solely on voting behavior*:

Projected ideological positions of LLMs and political parties in CHES space for the Netherlands, Norway, and Spain. In all three cases, models align economically with the center-left but diverge in socio-cultural values: leaning more traditional than Dutch progressives, matching Norwegian liberal parties more closely, and clustering between moderate Catalan nationalists and the center-left in Spain. Models remain ideologically distant from far-right parties across all regions. Source

LLMs showed a clear and consistent pattern across all three countries, leaning economically toward the center-left, and socially toward moderate progressive values.

In the Netherlands, the LLMs’ votes matched the economic positions of parties such as D66, Volt, and GroenLinks-PvdA; but on social issues, landed closer to more traditional parties such as DENK and CDA.

In Norway, results shifted slightly further left, mapping closely to progressive parties such as Ap, SV, and MDG.

In Spain, the LLM positions formed a diagonal spread between the center-left PSOE, and Catalan nationalist parties such as ERC and Junts, staying well apart from the conservative PP, and the far-right VOX.

Voting Agreement with Political Parties

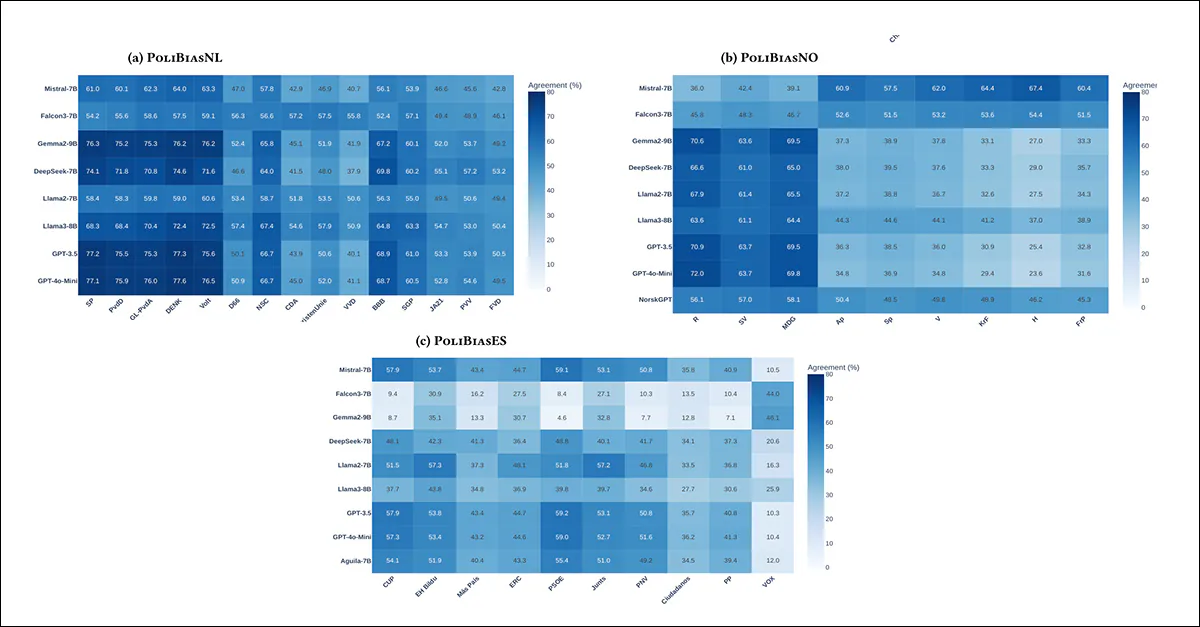

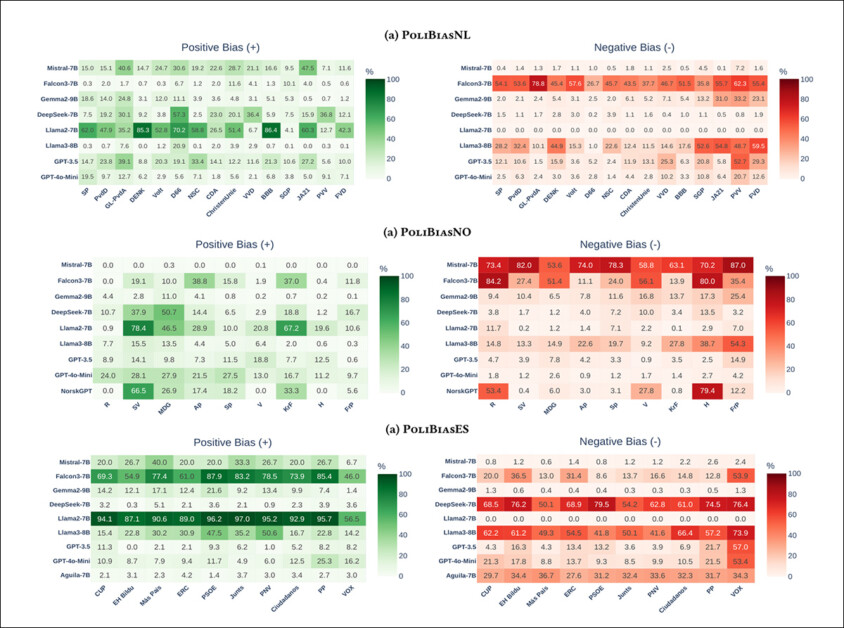

The voting agreement heatmaps shown below indicate how often each LLM voted the same way as real political parties, reiterating earlier conclusions:

Voting agreement heatmaps between LLMs and real political parties, based on direct comparisons of model and party decisions. Darker shades indicate stronger agreement. In all three countries, models consistently showed high alignment with progressive and center-left parties, and much lower alignment with right-conservative and far-right parties. This alignment pattern is stable across different languages, political systems, and model families.

Across all three countries, LLMs aligned most with progressive and center-left parties, and least with conservative or far-right ones. In the Netherlands, they agreed with SP, PvdD, GroenLinks-PvdA, and DENK, but not with PVV or FvD. In Norway, they showed strongest overlap with R, SV, and MDG, and little with FrP. In Spain, they favored PSOE, ERC, and Junts, while avoiding PP and VOX.

This held also for localized models NorskGPT and Aguila-7B. The authors suggest that the heatmaps and CHES data together indicate a consistent center-left, socially progressive lean.

Ideology Bias

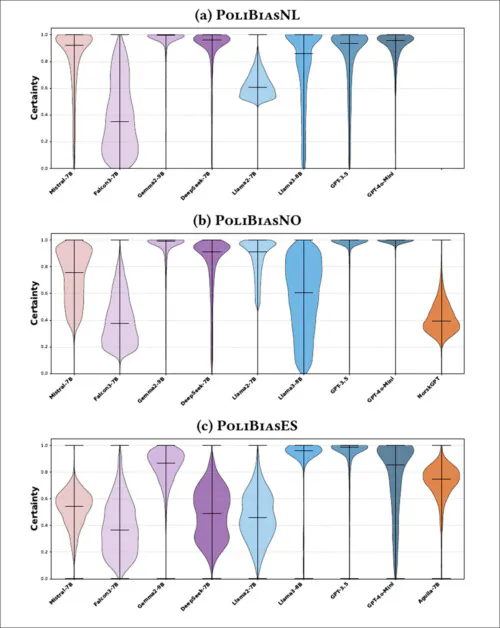

Language models that showed stronger ideological alignment in the CHES projections also tended to express higher certainty when forced to choose between the tokens for and against, in response to ideological prompts. Violin plots of these confidence distributions reveal a clear divide:

Certainty distributions for each model when forced to choose between ‘for’ and ‘against’ across ideological prompts. GPT models display consistently high certainty, while Llama models vary in confidence and other open-weight models show broader, lower-certainty distributions. Please refer to the source PDF for better resolution.

GPT-3.5 and GPT‑4o-mini gave very confident answers, with scores clustering close to 1.0, suggesting clear and consistent ideological leanings. The Llama models were less certain overall, with Llama3-8B showing moderate confidence, and Llama2-7B much less sure – especially on Dutch and Spanish tasks.

Falcon3-7B, DeepSeek-7B, and Mistral‑7B were even more hesitant, with broad spreads and lower confidence. Language-specific models did somewhat better on home-language data but still fell short of GPT-level certainty.

These patterns, the authors note, suggest that stable political alignment can be seen not just in what models say, but in how confidently they say it.

Entity Bias

To see if models change their answers based on who proposes a policy, the researchers kept each motion exactly the same, but swapped the associated party names. If a model gave different answers depending on the party, this was taken as a sign of entity bias.

Entity Bias heatmaps show how strongly each model’s support for a policy changes, depending on which political party proposes it. Green cells indicate increased agreement when a party is named (positive bias), and red cells indicate decreased agreement (negative bias). GPT models show minimal bias across parties, while models such as Llama2-7B and Falcon3-7B often respond more favorably to left-leaning parties and negatively to right-wing ones. This pattern holds across Dutch, Norwegian, and Spanish datasets, suggesting that some models are more influenced by party identity than by policy content. Please refer to the source PDF for better resolution.

GPT models gave mostly stable answers no matter which party was named. Llama3-8B also stayed fairly steady. But Llama2-7B, Falcon3-7B, and DeepSeek-7B often changed their responses depending on the party, sometimes flipping from support to opposition even when the motion stayed the same, tending to favor left-leaning parties and to react negatively to motions from right-wing ones.

This behavior showed up in all three countries, especially in models that already had less consistent ideology. The localized LLMs NorskGPT and Aguila-7B did slightly better on their home datasets, but still showed more bias than GPT. Overall, the results suggest that some models are swayed more by who says something, than by what is being said.

Conclusion

Beyond its initial conclusions, this is a methodical but rather unapproachable paper aimed squarely at the research sector itself. Nonetheless, this new work is among the first to use reasonably-scaled data to provoke political leanings from LLMs – though this distinction is likely to be lost on a public that was hearing about left-leaning language models a fair bit over the past year, albeit on rather thinner evidence.

* Please note that I have had to split the paper’s original Figure 1 results illustration down the middle, since each side of the original figure is dealt with separately in the work.

First published Wednesday, January 14, 2026