Anderson's Angle

Research Finds Women Use Generative AI Less, Due to Moral Concerns

A new study led by Oxford University concludes that women are using generative AI far less than men – not because they lack skills, but because they worry more about AI’s harm to jobs, privacy, mental health, and society itself.

As the primary targets of unauthorized deepfake content, women have been strongly associated with activism regarding this controversial strand of generative AI over the last seven years, leading to some notable victories in recent times.

However, a new study led by Oxford University argues that this characterization of female concern around AI is too narrow, finding that women are using generative AI of all kinds far less than men – not due to gaps in access or skill, but because they are more likely to view it as harmful to mental health, employment, privacy, and the environment.

The paper states:

‘Using nationally representative UK survey data from [2023–2024], we show that women adopt GenAI substantially less often than men because they perceive its societal risks differently.

‘Our composite index capturing concerns about mental health, privacy, climate impact, and labour-market disruption explains 9-18% of variation in adoption and ranks among the strongest predictors for women across all age groups–surpassing digital literacy and education for young women.’

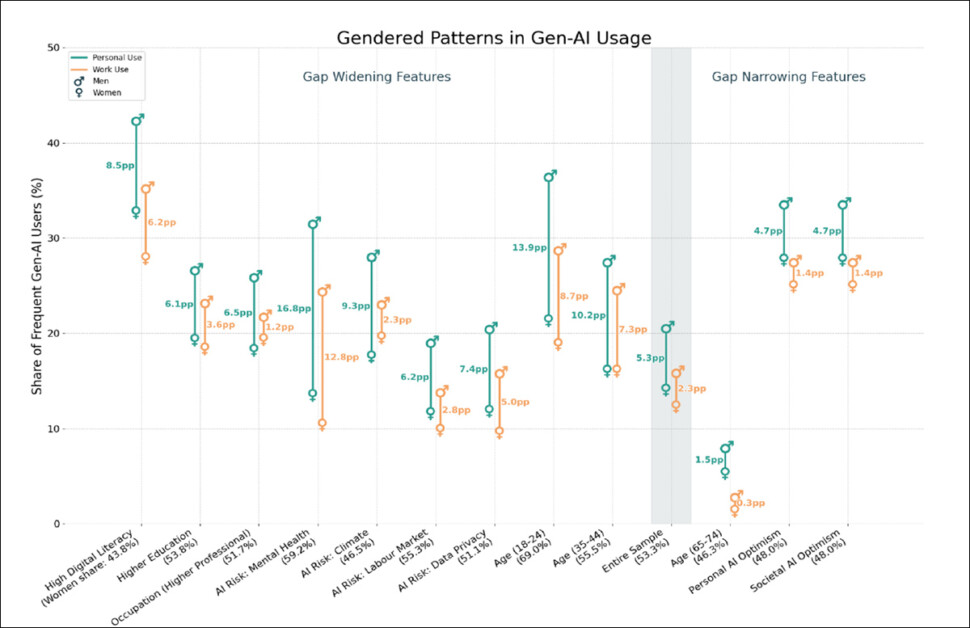

The widest gaps, according to the researchers, appear among younger, digitally fluent users who express strong concern about AI’s social risks, with gender differences in personal use reaching more than 45 percentage points:

Gender gaps in frequent generative AI use are widest among women with high digital literacy who also report strong concern about mental health, climate, privacy, and labor-market risks, while the smallest gaps appear among those with greater optimism about AI’s societal effects. Source

By matching similar respondents across successive survey waves in a synthetic-twin panel, the study finds that when young women grow more optimistic about AI’s societal impact, their use of generative AI rises from 13% to 33%, significantly closing the gap. Among those concerned about climate harms, the gender gap in generative AI use widens to 9.3 percentage points, and among those worried about mental health harms, it grows to 16.8 points, driven not by increased use among men but by marked declines among women.

The authors therefore identify an apparent cultural effect relating to gender*:

‘On average, women exhibit more social compassion, traditional moral concerns, and pursuit of [equity]. Meanwhile, moral and social concerns have been found to play a role in the acceptance of technology.

‘Emerging research on GenAI in education suggests that women are more likely to perceive AI use on coursework or assignments as unethical or equivalent to cheating, facilitating plagiarism, or spreading misinformation.

‘Greater concern for social good may partly explain women’s lower adoption of GenAI.’

They opine that women’s take on this, as observed in the study, is a valid one:

‘[Women’s] heightened sensitivity to environmental, social, and ethical impacts is not misplaced: generative AI systems currently carry significant energy demands, uneven labour practices, and well-documented risks of bias and misinformation.

‘This suggests that narrowing the gender gap is not only a matter of shifting perceptions, but also of improving the underlying technologies themselves. Policies that incentivize lower-carbon model development, strengthen safeguards around bias and wellbeing harms, and increase transparency around supply-chain and training-data practices would therefore address legitimate concerns—while ensuring that women’s risk awareness acts as a lever for technological improvement rather than a barrier to adoption.’

They further note that while the study shows clear evidence of the stated adoption gap, its findings are likely to be even higher outside the UK (which is the location of the new study).

The new paper is titled ‘Women Worry, Men Adopt: How Gendered Perceptions Shape the Use of Generative AI’, and comes from researchers across the Oxford Internet Institute, the Institute for New Economic Thinking in Belgium, and the Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society in Berlin.

Data and Approach

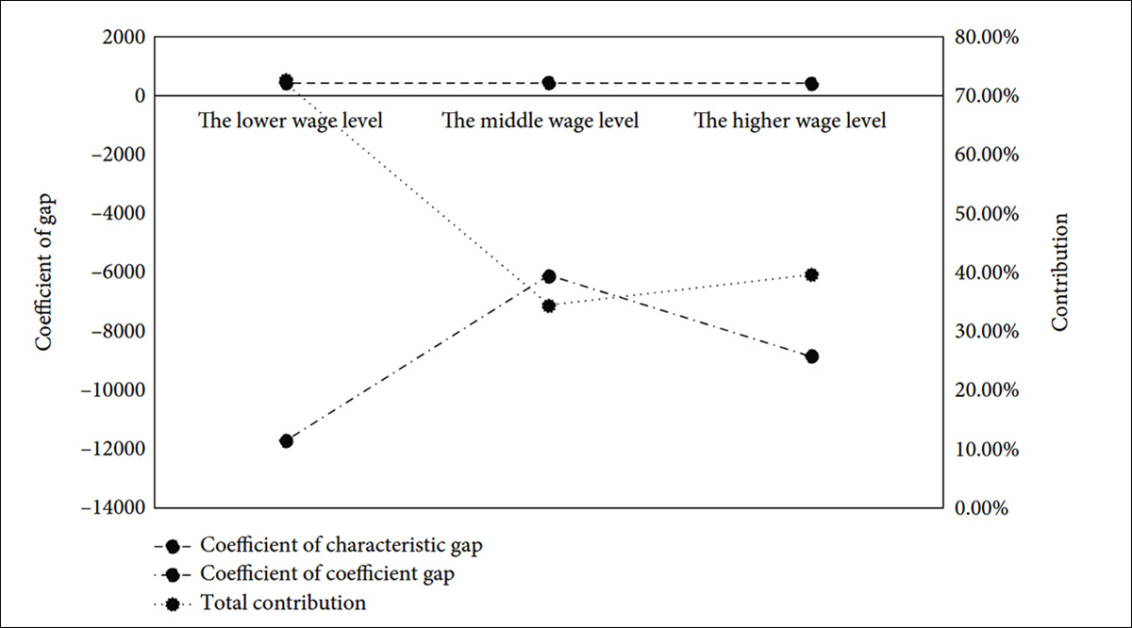

A new trend in research has indicated recently that women are using generative AI (of all kinds) less frequently than men, in spite of no difference in ability or access – a shortfall that has been estimated as a contributing factor to the gender wage gap lately, in line with prior trends relating lower internet use (in women) with lower salaries:

From the 2023 paper ‘Has Internet Usage Really Narrowed the Gender Wage Gap?: Evidence from Chinese General Social Survey Data’, an illustration of internet use narrowing the gender wage gap more significantly at lower wage levels, with diminishing returns as wage levels rise. Source

For the new work, the authors used the year-on-year study information available in the UK government’s Public attitudes to data and AI: Tracker survey initiative to analyze how perceptions of AI-related risks influence adoption patterns across gender, isolating risk sensitivity as a key factor in reduced use among women.

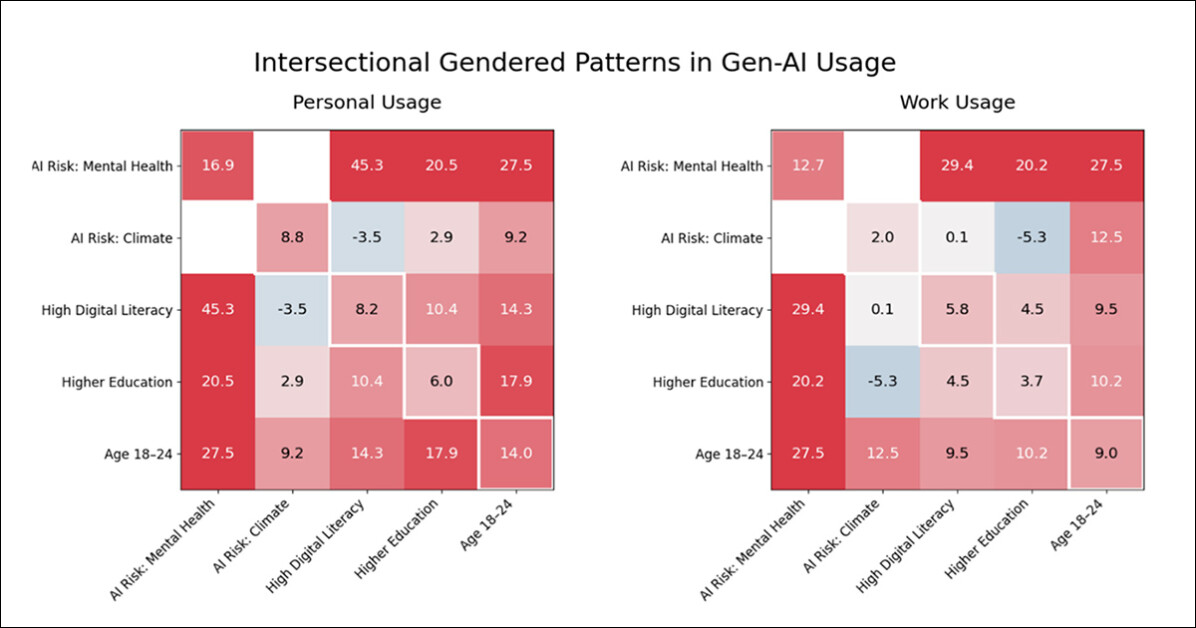

GenAI gender gaps grow much wider when risk concerns combine with other traits. The biggest gap, illustrated below, of 5.3 points, appears among women with high digital skills who see AI as a mental-health risk:

Gender gaps in GenAI use vary depending on both attitudes and demographics. Red cells show where men use GenAI more than women, especially in personal use. The largest gaps appear when high digital skills combine with concerns about mental health risks. In work settings, gaps grow wider with concerns about privacy or climate. Blue cells mark smaller or reversed gaps.

Mental‑health concerns tend to amplify the gender gap across most groups, with the effect strongest among younger and more digitally fluent users, while privacy worries also widen the divide and in some work contexts push the gap as high as 22.6 points.

Even among older respondents who express concern about AI’s climate impact, the gap remains substantial at 17.9 points, indicating that perceptions of harm weigh more heavily on women – including in groups where overall AI use is relatively low.

Risk Perceptions

To determine how strongly risk perception influences adoption, the researchers built a composite index based on concerns about AI’s effects on mental health, climate, privacy, and employment. This score was then tested alongside education, occupation, and digital literacy using random forest models split by age and gender, finding that across all life stages, AI-related risk perceptions consistently predicted generative AI use – often ranking higher than skills or education, especially for women:

Random forest models, stratified by age and gender, show that AI-related risk perception is a stronger predictor of generative AI use for women than for men, ranking among the top two features across all female age groups, and exceeding the influence of digital literacy and education. For men, digital literacy dominates, while risk perception ranks lower and plays a less consistent role. The models indicate that societal concerns shape AI adoption far more strongly for women than traditional skill or demographic factors. Please refer to the source PDF for better legibility and general resolution.

Across all age groups, concern about AI’s societal risks predicted generative AI use more strongly for women than for men. For women under 35, risk perception ranked as the second most influential factor shaping use, compared with sixth for men, while among middle-aged and older groups it ranked first for women and second for men.

Across models, risk perception accounted for between 9% and 18% of predictive importance, outweighing education and digital skill measures.

According to the paper, these results indicate that women’s lower adoption of generative AI stems less from concerns about personal risk and more from broader ethical and societal concerns. In this case, the hesitation appears driven by a stronger awareness of AI’s potential to cause harm to others, or to society, rather than to themselves.

Synthetic Twins

To test whether changing attitudes on these topics can shift behavior, the researchers used a synthetic-twin design, pairing similar respondents across two survey waves. Each person from the earlier wave was matched with a later respondent of the same age, gender, education, and occupation.

The team then compared changes in generative AI use among those who either improved their digital skills or became more optimistic about AI’s societal effects, allowing them to isolate whether greater literacy or reduced concern could actually increase adoption, especially among younger adults:

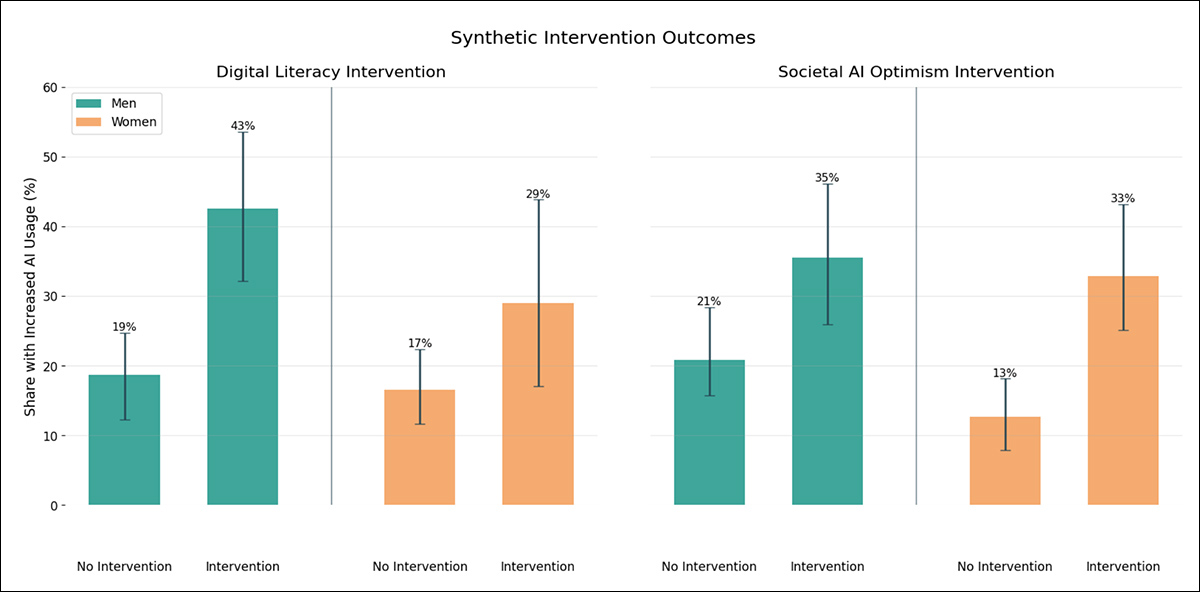

To test whether targeted changes affect AI use, the researchers compared young adults who improved digital skills or grew more optimistic about AI’s societal impact. Both changes raised adoption, but digital literacy widened the gender gap by helping men more. By contrast, greater optimism boosted women’s usage from 13% to 33%, narrowing the divide and suggesting that addressing ethical concerns may be more effective than skill-building alone.

Boosting digital literacy raised generative AI use for both genders, but widened the gap, with men benefiting more. In the full sample, women’s usage rose from 9% to 29%, while men increased from 11% to 36%.

Among younger adults, gains in digital literacy raised men’s usage sharply from 19% to 43%, while women’s increase from 17% to 29% was modest and not statistically significant. By contrast, greater optimism about AI’s societal impact produced a more balanced shift, with women rising from 13% to 33%, and men from 21% to 35%. In the full sample, women moved from 8% to 20%, and men from 12% to 25%.

Therefore, the paper indicates, while digital upskilling lifts adoption overall, it also tends to widen gender gaps – and re-framing perceptions of AI’s broader impact appears more effective at increasing women’s use, without disproportionately boosting uptake among men.

Conclusion

The significance of these findings seems to fork as the paper unfolds; earlier, as quoted above, the authors regard women’s greater global concern and ethical stance with approbation. Towards the end, a more reluctant and pragmatic viewpoint emerges – perhaps in the current spirit of the time – as the authors wonder if women will be ‘left behind’ due to their moral vigilance and misgivings:

‘[Our] findings point to broader institutional and labour-market dynamics. If men adopt AI at disproportionately higher rates during the period when norms, expectations, and competencies are still taking shape, these early advantages may compound over time, influencing productivity, skill development, and career progression.’

* My conversion of the authors’ inline citations to hyperlinks.

First published Thursday, January 8, 2026