Anderson's Angle

Reducing AI Image Hallucinations by Exaggerating Them

ChatGPT-style vision models often ‘hallucinate’ elements that do not belong in an image. A new method cuts down on these errors by showing the model exaggerated versions of its own hallucinations, based on captions – and then asking it to try again. This approach involves no retraining or need for extra data, and can be applied to a wide range of models and model types.

A new publication from China offers an interesting take on the annoyingly persistent problem of hallucinations in AI-generated image and videos – elements that clearly should not be in the image, based on the user’s request and input.

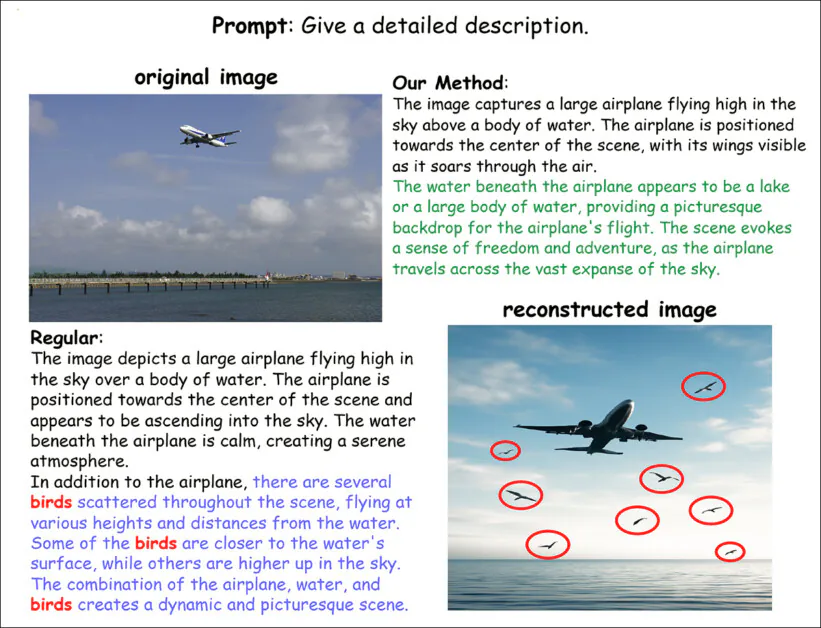

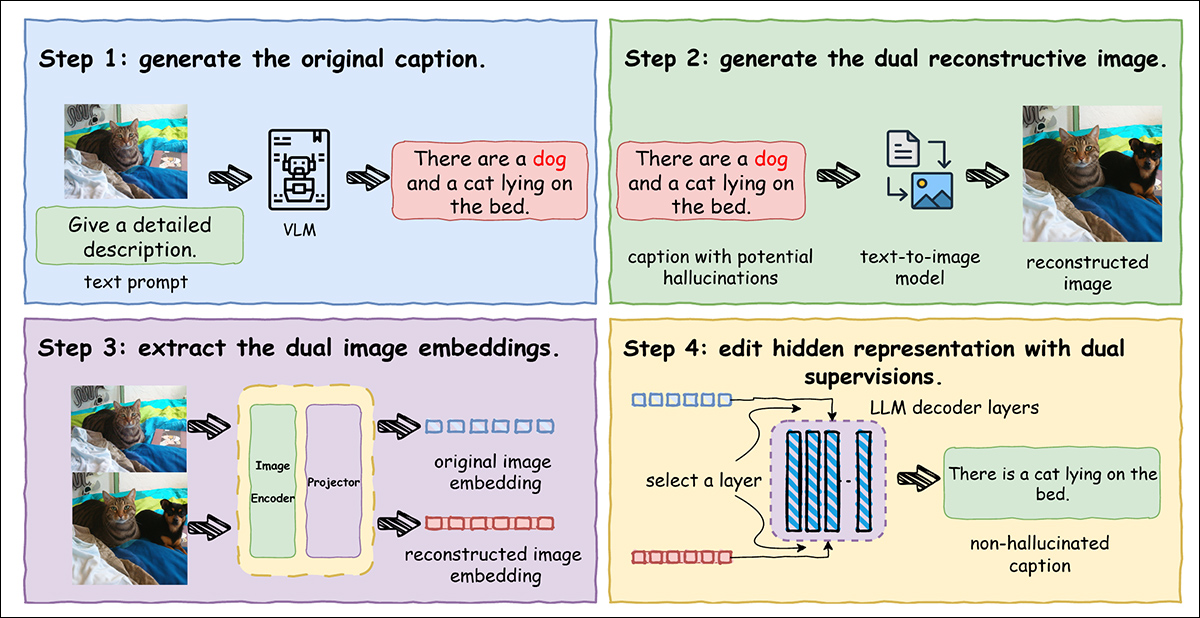

In essence, the system takes an image and lets the model describe it, as usual; it then turns that caption into a new image using a text-to-image model – and any extra objects or details in this second image will be direct representations of the model’s initial hallucinations. Then, by comparing the original and the generated images, the system gently steers the model away from those errors the next time it tries:

An illustration of how the new method identifies and reduces hallucinations in image captions. The regular model describes birds that do not exist in the original image, leading to a reconstructed image that adds them in. These errors are marked in red. By contrast, the proposed method avoids these invented details while keeping the caption specific and fluent. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2509.21997

The method begins by showing the model real images and having it describe them, including some descriptions featuring objects or details that are not actually present. These hallucinated captions are then used to generate synthetic images that make the errors easier to spot. By comparing the real and generated images, the system learns which internal patterns in the model tend to produce made-up content.

Once these error patterns are identified, they can be stored and used later. When the model is given a new image, the system will adjust its internal signals during captioning, nudging it away from the known patterns that cause hallucinations. This works in a single pass and does not require extra data, retraining, or any new image generation at test time.

The Tangled Web

In the example shown above, from the paper, we can see that entanglement is likely responsible for embellishing ‘birds’ into the input image, even though the first image appears to contain no birds.

Entanglement occurs when a model insists on associating certain concepts with certain other concepts, simply because the two (or more) concepts tend to appear frequently together in the original data distribution on which the model was trained. In this case, the model may have seen many pictures of planes+birds, causing an association that does not apply to the particular picture in question, but nonetheless intrudes on the derived caption.

Though entanglement can be mitigated by stopping training earlier (which, in general, makes the model maximally flexible and adaptable), this also reduces the detail and resolution of all trained concepts, leaving the model trainer with the perennial dilemma: create a model that is very flexible and disentangled; or create a model that is more powerfully generative, but also more likely to produce ‘associated’ hallucinations?

If the quality of captioning and attention to detail in the curation of the original data for a generative model had been better than logistics usually allow, captions for all the source images would have detailed every object in each picture, so that the trained model could have allocated them discrete and disentangled entries in its latent space.

As it stands, the self-serving practice of SEO captioning, combined with the fact that ad hoc hyperscale web-scraping remains the best source for training truly powerful generative models, means that image captions tend to fall considerably short of this standard:

An illustration of how weak captions limit the usefulness of LAION images for training models like Stable Diffusion. Many of the text labels are shallow, vague, or optimized for SEO rather than accurate description, making it harder for the model to learn fine-grained visual concepts such as facial features. (Original source was https://rom1504.github.io/, now defunct).

Therefore, since a foundational solution is unlikely to ever be practicable, the reduction of LLM/VLM hallucinations by workarounds and compromises has now become a strong sub-strand in the literature.

The new Chinese technique unveiled this week, the authors state, was tested across a variety of architectures in diverse conditions, and could indicate a useful way to reduce ‘hallucination pollution’.

They say:

‘Extensive experiments across multiple benchmarks show that our method significantly reduces hallucinations at the object, attribute, and relation levels while largely preserving recall and caption [richness].’

The new paper is titled Exposing Hallucinations To Suppress Them: VLMs Representation Editing With Generative Anchors, and comes from three researchers across the University of Science and Technology of China, and Nanjing University.

Method

The authors have devised an end-to-end pipeline, shown below, designed to expose and suppress hallucinations in image captions:

An illustration of the full pipeline. A vision-language model first generates a caption from the input image, which may include hallucinated content. This caption is then used to produce a reconstructed image via a text-to-image model, making any hallucinations easier to spot. Embeddings from both the original and reconstructed images are extracted and used to guide adjustments inside the decoder, helping the model suppress hallucinated details while preserving caption quality.

Starting from a real input image, a vision-language model generates a descriptive caption that may contain invented objects or relationships. This caption is then fed into a text-to-image generator to create a reconstructed image showing exactly what the caption describes. Comparing this reconstructed image with the original makes the fabricated content obvious and measurable, turning subtle errors in text into visible differences that the system can target and reduce.

To guide the model away from ‘inventing’ details, the system compares two versions of the same image: the original and a reconstructed one based on the caption. Each image is converted into a compact embedding that captures its content.

The original image acts as a reliable reference, while the reconstructed one highlights where hallucinations may have crept in. By adjusting its internal representations to move closer to the original and further from the reconstructed, the model learns to correct itself automatically. Since this process does not rely on hand-tuned rules or outside data, it remains fully self-supervised.

The paper states:

‘Hallucinations in MLLMs are intrinsically difficult to detect because they are linguistically well-formed and often indistinguishable from faithful descriptions at the text level. The discrepancy lies not in language plausibility but in the misalignment with visual evidence, which the model itself is typically insensitive to.

‘To address this, we introduce a hallucination exposure mechanism that leverages generative reconstruction to convert implicit inconsistencies into explicit and observable signals.’

Given an input image and its caption, the system uses the FLUX.1-dev text-to-image model to recreate an image from the caption alone. This recreated image tends to exaggerate the meaning of the caption, making any false details more obvious. These amplified errors then serve as useful signals that help the model recognize and correct its own mistakes.

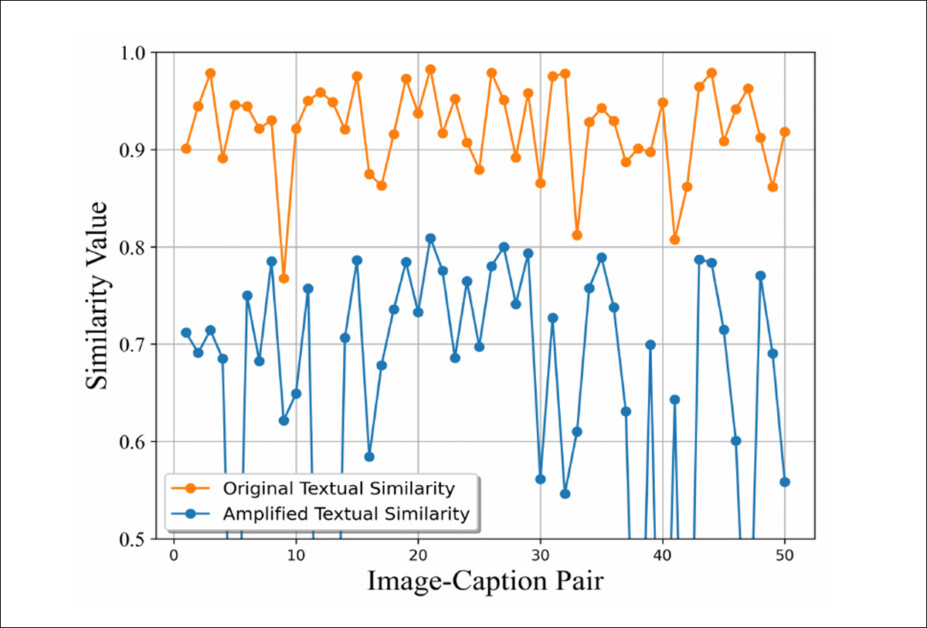

To test their approach, the authors injected hallucinations into captions and used the text-to-image model to generate reconstructed images. These images were then re-captioned by LLaVA, and the semantic similarity between the original and hallucinated captions evluated:

An illustration of how the hallucination amplification mechanism makes subtle errors visible. Each point shows the similarity between captions of the original and reconstructed images for one image-caption pair. The orange line represents similarity measured directly between original and hallucinated captions, which stays high and masks small mistakes; the blue line represents similarity after reconstruction, which drops sharply, showing that the process turns hidden hallucinations into clear semantic markers that can be detected and corrected.

The similarity drops sharply after reconstruction, showing that the process makes subtle errors more detectable.

Data and Tests

Validating the effectiveness of the new method involved the use of three apposite benchmarks: Caption Hallucination Assessment with Image Relevance (CHAIR); MLLM Evaluation benchmark (MME); and Pooling-based Object Probing Evaluation (POPE).

From the CHAIR release paper: examples of hallucinated objects generated by two leading captioning systems, TopDown and NBT, where each model invents visual elements not actually present in the image, such as laptops, sinks, or surfboards. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1809.02156

Standard metrics like hallucination rate or recall can be misleading, since a model might avoid hallucinations simply by producing short or vague captions. To account for the tradeoff between recall and hallucination, a combined metric called Hallucination and Recall (HAR@β) was used, which scores captions based on both accuracy and completeness, and which allows the balance to be adjusted depending on whether avoiding errors or including more detail is more important.

POPE was used to assess context-sensitive object hallucinations, and MME to evaluate attribute-level hallucinations, with both framed as Yes-or-No judgment tasks.

Experiments were conducted across diverse representative datasets, using the aforementioned Flux model and the LLaVA-v1.5-7B variant. The datasets employed were Microsoft COCO; A-OKVQA; and GQA.

Latent editing was conducted for the models’ second layer, in accordance with prior related work, while hyperparameters and temperature were consistent across all models.

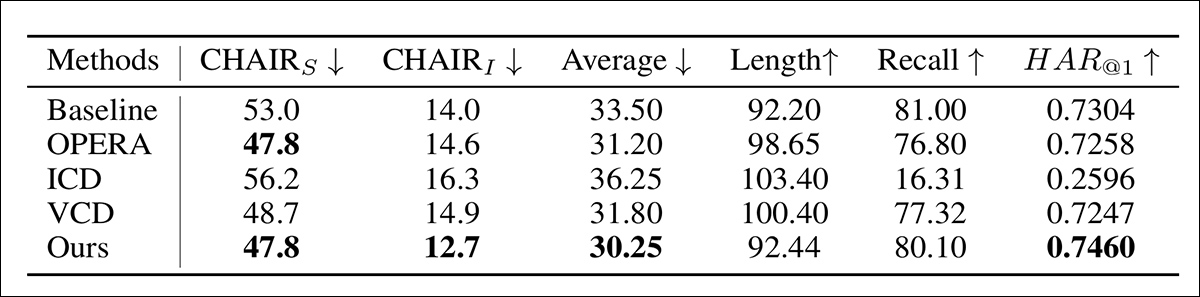

Initial results on CHAIR are presented below*:

Performance on CHAIR benchmark for hallucination mitigation, evaluated using multiple metrics.

Of these results, the authors comment:

‘[Our method consistently outperforms other baselines on both CHAIRS and CHAIRI[*] , demonstrating its superior effectiveness in suppressing hallucinations. Meanwhile, although nearly all methods inevitably reduce recall while suppressing hallucinations, reflecting a trade-off between faithfulness and informativeness, our approach achieves the smallest drop.

‘This demonstrates that our method captures a broad range of ground-truth objects. With the HAR@β metric, our method achieves the highest score, highlighting its ability to reduce hallucinations while maintaining coverage.’

The researchers attribute these strong results to the dual-supervision setup, where clean semantics from the original image were reinforced, at the same time as misleading signals from the reconstructed image were suppressed. Because the adjustment targeted only the direction associated with hallucinations, the rest of the representation was left intact, allowing the system to correct errors without sacrificing detail or informativeness.

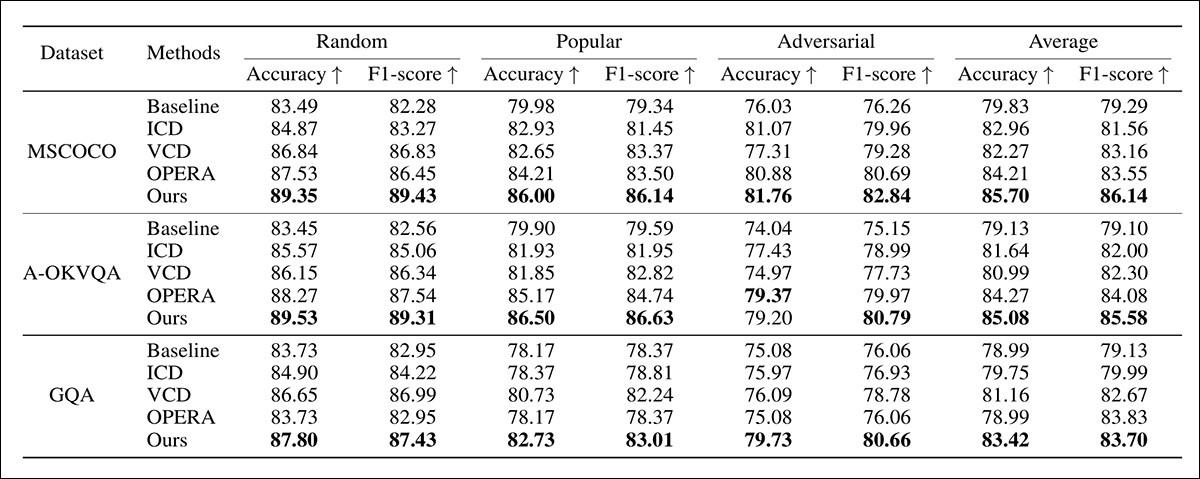

Comparison of performance on the POPE benchmark under various configurations and datasets.

Regarding the results on POPE, shown in the results table above, the paper asserts:

‘It can be observed that our method consistently achieves the best performance across all settings. Notably, our method can achieve up to +5.95% accuracy and +6.85% F1 score on average, outperforming other training-free approaches by a large margin.

‘Therefore, these results demonstrate that our method provides a reliable and generalizable solution across different levels of difficulty.’

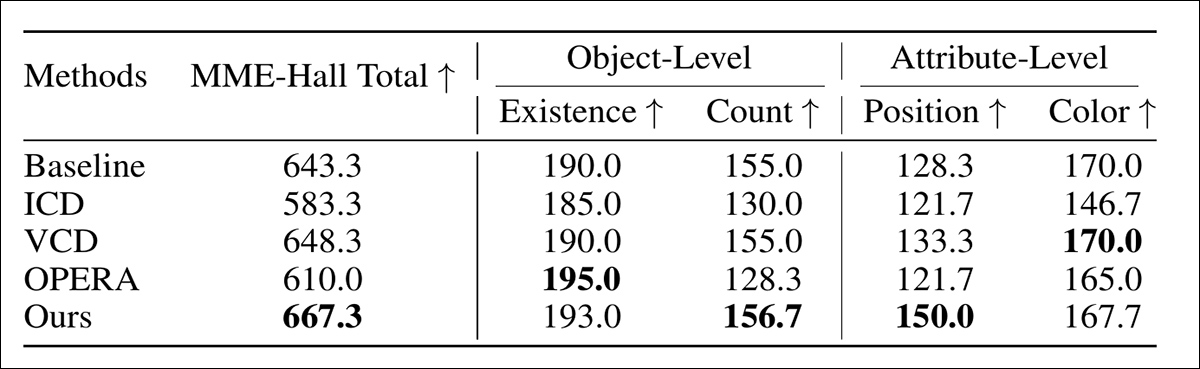

From the third testing round, performance comparisons over MME.

The final main test was on MME, with the results shown above. However, among other omissions , it mentions the Method ‘OPERA’, which is not defined anywhere in the main paper or the appendix. Though, the authors claim strong performance on MME, without adequate definitions of the methods, we should perhaps leave the results section at this point.

An illustration from the MME benchmark using LLaVA-v1.5-7B, showing how the baseline model produces a hallucinated answer while the proposed method gave the correct response, with the reconstructed image making the hallucination more apparent.

Conclusion

Though this paper is clearly rushed, and suffers from the lack of structure, focus and clarity which has come increasingly into evidence in the literature over the past 12 months (perhaps not unrelated to the rapidly-growing use of AI in academic research), the central mechanism presented remains ingenious.

While this end-to-end approach does not require retraining, and appears applicable across a range of architectures, it would have been insightful to see more test candidates; and it must also be considered that an interstitial system of this kind will at the very least introduce latency, and some extent of extra power requirement – not a minor issue at scale.

* Unconventionally, the main body of this paper presents results with headings that are only explained in the appendix material, and not in the main paper – an increasingly-seen bad habit in the literature, as researchers seek to limit the central thesis to 8-9 pages, even when the material will not allow it. In any case, the CHAIR benchmark, used to evaluate object hallucination in captions, was based on a 500-image MSCOCO subset from earlier work. Two forms were used: CHAIRs, measuring how often hallucinations appeared in any given caption; and CHAIRI, measuring how many of the mentioned objects were hallucinated. HAR@β , introduced in the main paper, was defined as an Fβ-style combination of hallucination suppression and object recall.

First published Tuesday, September 30, 2025