Anderson's Angle

Coding AIs Tend to Suffer From the Dunning-Kruger Effect

New research shows that coding AIs such as ChatGPT suffer from the Dunning-Kruger Effect, often acting most confident when they are least competent. When tackling unfamiliar or obscure programming languages, they claim high certainty even as their answers fall apart. The study links model overconfidence to both poor performance and lack of training data, raising new concerns about how much these systems really know about what they don’t know.

Anyone who has spent even a moderate amount of time interacting with Large Language Models about factual matters will already know that LLMs are frequently disposed to give a confidently wrong response to a user query.

Along with more overt forms of hallucination, the reason for this empty boastfulness is not 100% clear. Research published over the summer suggests that models give confident answers even when they know they are wrong, for instance; though other theories ascribe overconfidence to architectural choices, among other possibilities.

What the end user can be certain about is that the experience is incredibly frustrating, since we are hard-coded to put faith in people’s estimations of their own abilities (not least because in such cases there are consequences, legal and otherwise, to a person over-promising and under-delivering); and a kind of anthropomorphic transference means we tend to replicate this behavior with conversational AI systems.

But an LLM is an unaccountable entity which can and will effectively return a ‘Whoops! Butterfingers…’ after it has helped the user to inadvertently destroy something important, or at least waste an afternoon of their time; assuming it will admit liability at all.

Worse, this lack of prudent circumspection seems impossible to prompt away, at least in ChatGPT, which will abundantly reassure the user of the validity of its advice, and explain the flaws in its thinking only after the damage is done. Neither updating the system’s persistent memory, nor the use of repetitive prompts seem to have much impact on the issue.

People can be likewise obstinate and self-deluding – though anyone who erred quite so deeply and often would likely be fired early. Such as these suffer from opposite of ‘imposter syndrome’ (where an employee fears they have been promoted above their capabilities) – the Dunning Kruger effect, where a person significantly overestimates their ability to perform a task.

The Cost of Inflation

A new study from Microsoft examines the value of the Dunning-Kruger effect as it relates to the effective performance of AI-aided coding architectures (such as Redmond’s own Copilot), in a research effort that is the first to specifically address this sub-sector of LLMs.

The work analyzes how confidently such code-writing AIs rate their own answers against how well they actually performed, across dozens of programming languages. The results show a clear human-like pattern: when the models were least capable, they were most sure of themselves.

The effect was strongest in obscure or low-resource languages, where training data was thin – the weaker the model or the rarer the language, the greater the illusion of skill:

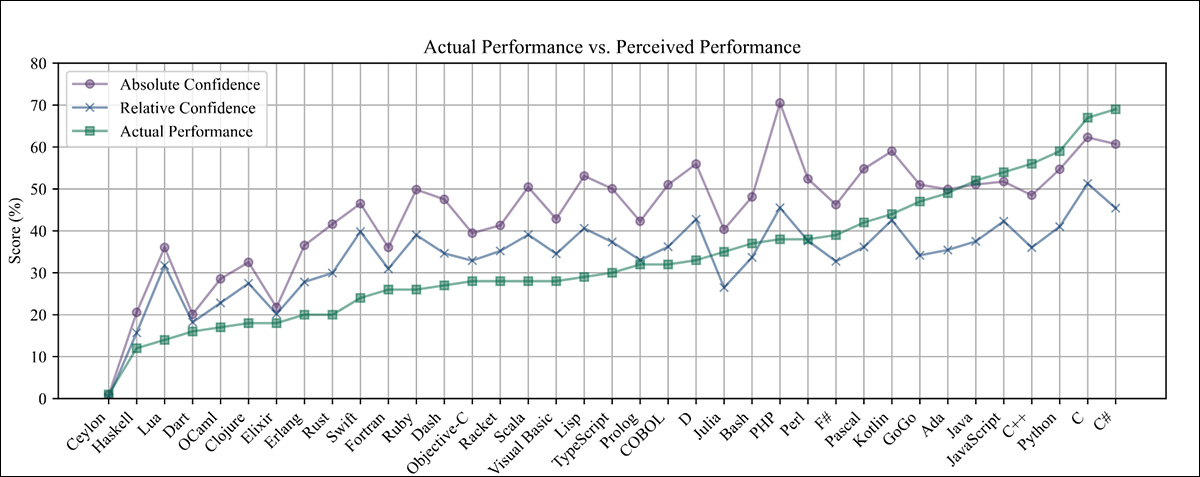

GPT-4o’s actual and perceived performance across programming languages, sorted by true performance. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.05457

The four authors, all equal contributors working for Microsoft, contend that the work raises new questions about how much these tools can be trusted to judge their own output, and they state:

‘By analyzing model confidence and performance across a diverse set of programming languages, we reveal that AI models mirror human patterns of overconfidence, especially in unfamiliar or low-resource domains.

‘Our experiments demonstrate that less competent models and those operating in rare programming languages exhibit stronger DKE-like bias, suggesting that the strength of the bias is proportionate to the competence of the models. This aligns with human experiments for the bias.’

The researchers contextualize this line of study as a way to understand how model confidence becomes unreliable when performance is weak, and to test whether AI systems display the same kind of overconfidence seen in humans – with downstream implications for trust and practical deployment.

Though the new paper defies Betteridge’s law of headlines, it is nonetheless titled Do Code Models Suffer from the Dunning-Kruger Effect?. While the authors state that code has been released for the work, the current preprint does not carry any details about this.

Method

The study tested how accurately coding AIs could judge their own answers by giving them thousands of multiple‑choice programming questions, with each question belonging to a specific language domain, from Python and Java to Perl and COBOL:

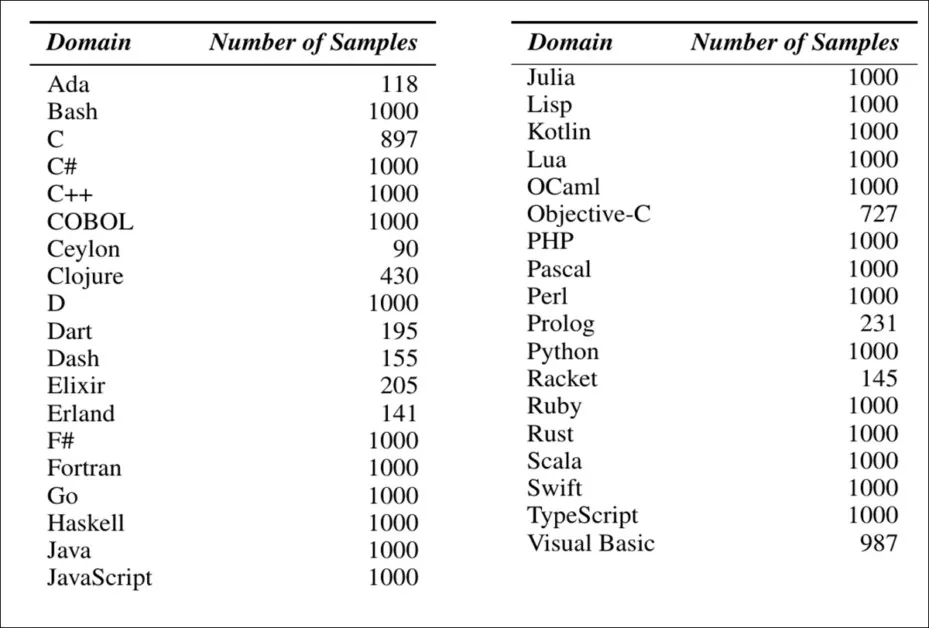

Programming language domains used in the study, along with the number of multiple‑choice coding questions sampled for each domain.

The models were tasked with picking the correct option, and then estimating how confident they were in their choice, with their actual performance measured by how often they got the answer right – and their self‑assessed confidence indicating how good they believed they were. Comparing these two metrics allowed the researchers to see where confidence and competence diverged.

To measure how confident the models appeared to be, the study used two methods: absolute confidence and relative confidence. In the first, the model was asked to give a score from zero to one alongside each answer, with its confidence for a given language defined by the average of those scores across questions in that language.

The second method looked at how confident the model was when choosing between two questions; for each pair, the model had to say which one it felt more sure about. These choices were then scored using ranking systems originally designed for competitive games, treating each question as if it were a player in a match. The final scores were normalized and averaged for each language to give a relative confidence score.

Two established forms of the Dunning–Kruger Effect are examined in the paper: one that tracks how a single model misjudges its performance across different domains; and another that compares confidence levels between weaker and stronger models.

The first form, called intra-participant DKE, looks at whether a single model becomes more overconfident in languages where it performs poorly. The second, inter-participant DKE, asks whether models that perform worse overall also tend to rate themselves more highly.

In both cases, the gap between confidence and actual performance is used to measure overconfidence, with larger gaps in low-performance settings pointing to DKE-like behavior.

Results

The study tests for the Dunning–Kruger Effect across six large language models: Mistral; Phi‑3; DeepSeek‑Distill; Phi‑4; GPT‑0.1, and GPT‑4o.

Each model was tested on multiple-choice programming questions from the publicly-available CodeNet dataset, with 37 languages* represented to reveal how confidence and accuracy varied across familiar and obscure coding domains.

The inter-model analysis shows a clear Dunning-Kruger pattern:

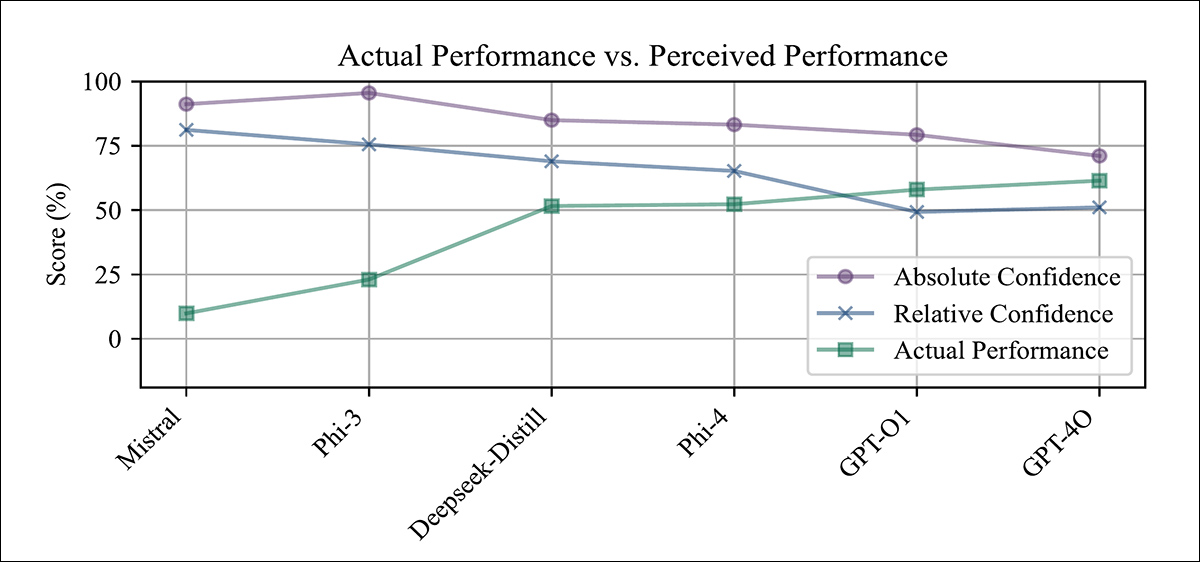

Actual versus perceived performance across six code models, showing how lower-performing models such as Mistral and Phi‑3 display high confidence despite poor accuracy, while stronger models such as GPT‑4o show more calibrated or even underconfident behavior.

Models with lower accuracy, including Mistral and Phi‑3, tended to overestimate their own abilities, while higher-performing systems such as GPT‑4o showed confidence levels that more closely matched their real performance, particularly when judged by relative confidence.

The results also indicate that the most capable models may sometimes underestimate themselves (a pattern that absolute confidence scores fail to capture).

Results also indicate that the intra-model analysis also supports the presence of the Dunning–Kruger Effect. In the results chart shown at the start of the article, we see how each model performed across different programming languages, arranged by actual performance.

In languages where the models scored poorly, particularly in rare or low-resource ones such as COBOL, Prolog, and Ceylon, their confidence was noticeably higher than their results justified. In well-known languages such as Python and JavaScript, their confidence aligned more closely with their real accuracy, and sometimes even fell below it.

This pattern appeared in both absolute and relative confidence measures, suggesting that models are less aware of their own limits when operating in unfamiliar coding domains.

Treating models as participants introduced some limitations, since the small number of models in play affects diversity; differences within a single model’s outputs are ignored; and the data distribution may not reflect that of real human participants.

To account for this, the study tested three alternative setups: firstly, each model was given a distinct persona; secondly, responses were sampled at a higher temperature to create more variation; thirdly, the prompts were paraphrased multiple times, with each version treated as a separate participant:

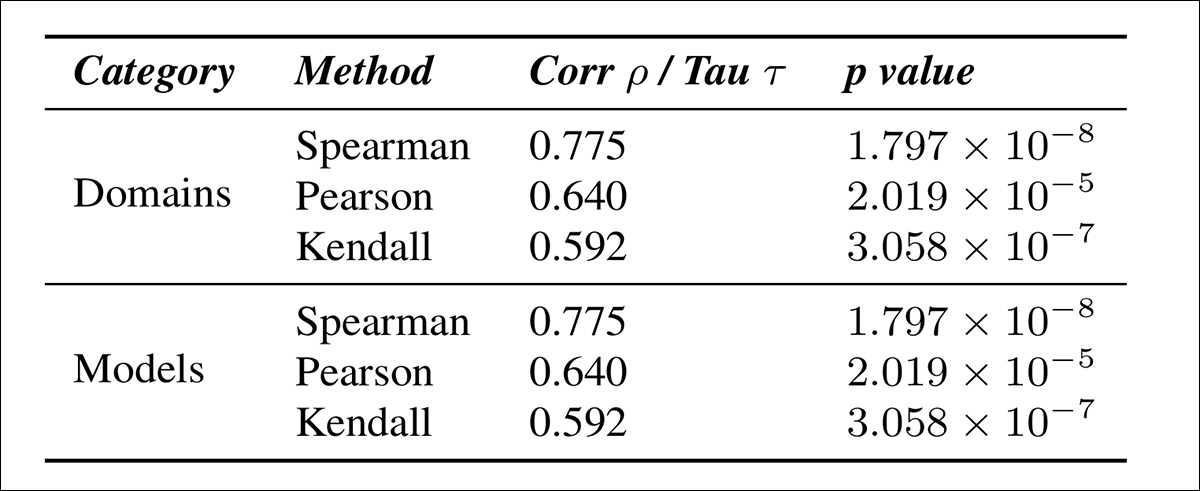

Correlation between overconfidence and actual performance across different experimental setups, showing that the Dunning-Kruger pattern remains consistent under all conditions and is strongest when multiple diverse responses are sampled from the same model.

The results table shown above indicates how strongly the Dunning-Kruger Effect manifests under these conditions, remaining present in every case; and that DKE was most pronounced when multiple responses were sampled from the same model at high temperature.

To better understand how perceived performance diverges from actual performance, the study compared absolute and relative confidence estimates, by calculating how much each model overestimated its own ability (specifically, the difference between its confidence score and its actual accuracy), and then measuring how that overestimation related to the model’s true performance:

Correlation between overconfidence (measured as absolute minus relative confidence) and actual accuracy across programming domains and model types, showing that greater overestimation is consistently associated with lower performance.

The results table above illustrates how overestimation relates to actual performance, both across programming domains, and across models. In both cases, we can see that models with lower accuracy tend to show greater overconfidence.

Further, specialized models trained on narrower domains showed stronger DKE effects than generalist ones:

Correlation between overestimation and true performance for base, single-domain, and multi-domain specialized models, showing stronger DKE effects as specialization increases.

Using the MultiPL-E dataset across eight programming languages, the authors found that single-domain training led to greater overconfidence than multi-domain or base setups, suggesting that DKE worsens with increased specialization.

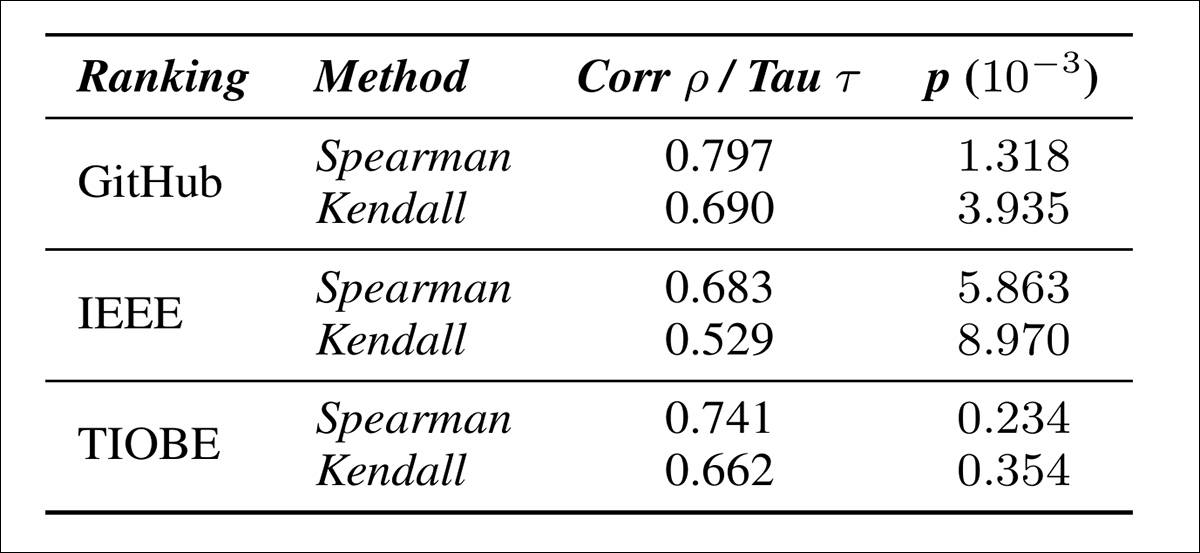

Tests also found that models tend to be more overconfident in rare programming languages. Across GitHub, IEEE, and TIOBE rankings, rarity strongly correlates with higher perceived confidence, peaking at 0.797:

Correlation between model overconfidence and language rarity, using three popularity rankings. Less common languages are associated with higher perceived performance.

Finally, the authors tested whether the Dunning-Kruger effect appears in code generation, by evaluating models on the MultiPL-E dataset across the Ada, Dart, Prolog, Swift, C++, Python, C#, and Elixir languages.

Although the effect was still present, it was notably weaker than in the multiple-choice questions setting, likely reflecting the greater difficulty in assessing confidence and correctness in open-ended tasks:

Correlation between overestimation and actual performance in open-ended code generation, based on MultiPL‑E results across eight programming languages.

In considering the still-disputed explanation for the Dunning-Kruger effect, the authors conclude:

‘One potential explanation that may be common to both humans and AI models is the meta-cognitive explanation, which states that assessing the quality of a performance of a skill is a crucial part of acquiring a skill.

‘This explanation can potentially be tested experimentally in AI models with a controlled study of different training strategies and whether they all lead to simultaneous improvements in performance and in the ability to assess quality of performance. However, this study is significantly beyond the scope of this paper, and we leave it for future work.’

Conclusion

Even in its native domain, the Dunning-Kruger effect (as the paper notes) may be attributable either to a statistical or cognitive cause. If to a statistical cause, the application of a hitherto uniquely human syndrome to a machine learning context is actually quite valid.

Though the authors speculate that the cause could be found to be ‘cognitive’ in both cases, that would require a slightly more metaphysical standpoint.

Perhaps the most interesting finding in the paper is the extent to which several coding LLMs tend to double-down in their least favorable circumstances, i.e., by exhibiting maximum confidence when dealing with the sparsest or least-known languages – which would be an almost immediately self-defeating stratagem in a real-world work environment.

* The programming languages used were Ada, Bash, C, C#, C++, COBOL, Ceylon, Clojure, D, Dart, Dash, Elixir, Erland, F#, Fortran, Go, Haskell, Java, JavaScript, Julia, Lisp, Kotlin, Lua, OCaml, Objective-C, PHP, Pascal, Perl, Prolog, Python, Racket, Ruby, Rust, Scala, Swift, TypeScript and Visual Basic.

First published Wednesday, October 8, 2025