Anderson's Angle

AI Pollution in Search Results Risks ‘Retrieval Collapse’

As AI content pollutes the web, a new attack vector opens in the battleground for cultural consensus.

Research led by a Korean search company argues that as AI-generated pages encroach into search results, they undermine the stability of search and ranking pipelines and weaken systems – such as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) – that rely on those rankings to decide what information is surfaced and trusted, thereby increasing the risk that misleading or inaccurate material will be treated as authoritative.

The term coined for this syndrome by the researchers is Retrieval Collapse, as distinct from the known threat of model collapse (where AI trained on its own output becomes progressively worse).

In a Retrieval Collapse scenario, AI-generated content progressively dominates search engine results, to the extent that even when answers remain superficially accurate, the underlying evidence base will have become divorced from original human sources. Nonetheless, this ‘rootless’ data seems poised to achieve a high place in search results*:

‘With the proliferation of AI-generated text, challenges in attribution and pre-training data quality have intensified. Unlike traditional keyword spam, modern synthetic content is semantically coherent, allowing it to blend into ranking systems and propagate through pipelines as authoritative evidence.’

The paper asserts that this would create a ‘structurally brittle’ environment in which ranking signals favor AI-produced, SEO-optimized pages, displacing human-authored sources over time in an insidious way, i.e., without triggering obvious drops in answer quality:

‘The [growth] of AI-generated content on the Web presents a structural risk to information retrieval, as search engines and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems increasingly consume evidence produced by the Large Language Models (LLMs).

‘We characterize this ecosystem-level failure mode as Retrieval Collapse, a two-stage process where (1) AI-generated content dominates search results, eroding source diversity, and (2) low-quality or adversarial content infiltrates the retrieval pipeline.’

The researchers contend that once the ‘dominance’ phase is established, the same retrieval pipeline becomes more susceptible to deliberate pollution, since adversarial pages can exploit the same optimization mechanisms to gain visibility*:

‘By establishing the framework of Retrieval Collapse, this work lays the foundation for understanding how synthetic content reshapes information retrieval. To mitigate these risks, we propose a shift toward Defensive Ranking strategies that jointly optimize relevance, factuality, and provenance.’

Retrieval Collapse arguably would exacerbate model collapse, since it adds a layer of malicious intent onto the ‘photocopy effect’ of entropy, where AI increasingly feeds on AI-generated output. Besides affecting the apparent consensus on ‘truth’ in real-time search results, inaccuracies and attacks could later become enshrined in trained LLMs as authoritative sources.

The new work is titled Retrieval Collapses When AI Pollutes the Web, and comes from three researchers at Naver Corporation.

Method

To test how AI-generated content propagates through retrieval systems, the researchers randomly sampled 1000 query/answer pairs from the MS MARCO dataset and benchmark, which consists of open-domain questions paired with human-validated reference answers. These were used both to ground retrieval and to evaluate the factual correctness of generated responses.

For each MS MARCO query in the tests, ten web documents were retrieved from Google Search, based on the top-ranking SEO results for each term, ultimately producing a pool of 10,000 documents.

The documents’ factual validity was assessed by comparing each of them against the MS MARCO ground truth, using GPT-5 Mini as the judge.

Content Farm Simulation

To simulate the quality level (of normal, non-adversarial) articles associated with content farms, the authors used the economical GPT-5 Nano OpenAI model to actually generate new synthetic articles, since this is the ‘affordable’ level of AI likely to be used by content mills. GPT-5 Mini, used to assess the output, is a slightly more capable model.

Conversely, to simulate adversarial posts (i.e., content designed to spread misinformation or which otherwise features misinformation), no real-world references were used. Instead, first drafts of the samples were created with a conventional clickbait/SEO generator, and then passed to GPT-5 Nano, which was tasked with replacing a certain number of facts with plausible but untrue alternatives. GPT-5 Nano also performed semantic re-ranking for the purposes of the experimental context.

To simulate AI saturation over time, a 20-round contamination process was run, in which one synthetic document was added per query to a fixed set of ten original documents, increasing the AI share from 0% to 66.7%.

For the SEO-style pool, the generator was prompted to ‘act as an SEO specialist’, and to integrate high-IDF keywords from the original documents to boost retrieval likelihood.

For the adversarial pool, the prompt was designed to preserve fluent, natural-sounding prose while subtly altering named entities and numerical details, creating documents that would not flag statistical filters, while quietly eroding factual accuracy.

Metrics

Three metrics were adopted for the experiments: Pool Contamination Rate (PCR), to determine how much of the overall document pool was AI-generated; Exposure Contamination Rate (ECR), to measure how much of the top ten search results came from AI sources (indicating what actually entered the retrieval pipeline); and Citation Contamination Rate (CCR), to record how much of the evidence cited in the final answer was synthetic.

To examine practical impact, both the quality of retrieved sources and the integrity of the final answer were tested. Precision@10 (P@10) captured how many of the top ten results were actually correct when checked against the MS MARCO ground truth; and Answer Accuracy (AA) measured whether the generated response matched that same reference answer, with GPT-5 Mini used to determine whether the meaning was consistent.

Tests

Initially, the authors tested their method against the original pool of documents extracted from SERPS, i.e., before they were used as material to generate synthetic data, and they note that their LLM ranker achieved ‘strong retrieval quality’, outperforming the BM25 Ranker baseline.

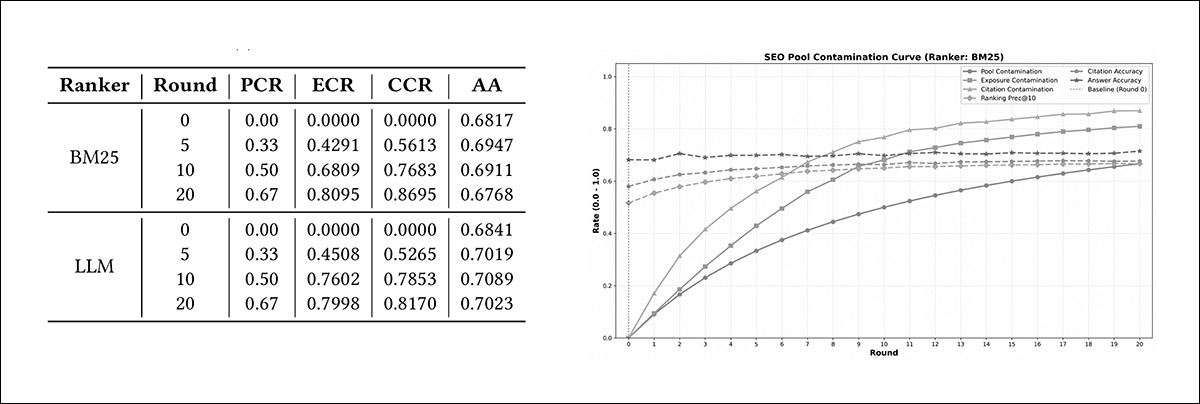

The first of the two primary scenario tests, dubbed Dominance and Homogenization, was an examination of the way that SEO-shaped synthetic documents affect retrieval results:

Left: contamination curves for Scenario 1 under BM25 and LLM rankers show Pool Contamination Rate (PCR) rising with each round, with Exposure Contamination Rate (ECR) and Citation Contamination Rate (CCR) increasing more steeply as synthetic documents crowd into the top results; Answer Accuracy (AA) remains broadly stable. Right: the corresponding table reports the same progression numerically across rounds 0, 5, 10, and 20, detailing PCR, ECR, CCR, and AA for both rankers.

As more AI-written pages were gradually added to the test environment, they began to dominate the top search results faster than expected. When AI content made up 50% of all available documents, more than 68% of BM25’s top ten results were already AI-generated; and when the share of AI material rose to 67%, over 80% of its top results came from AI sources.

The LLM-based ranker showed an even stronger tendency in this direction, with around 76% of its top results drawn from AI-written pages, when those pages accounted for only half of the overall pool – and it continued to rely on them more heavily than BM25, as their presence increased. The authors comment:

‘This pattern shows that SEO-optimized content disproportionately activates ranking signals, causing both models to converge rapidly toward synthetic-dominated evidence.’

Regarding the tension between factual stability and diversity collapse, the paper notes that notwithstanding the ‘dramatic’ shifts shown in retrieved evidence, Answer Accuracy remained stable, or else improved:

‘Because SEO documents are high-quality and topically aligned, retrieval appears healthy when measured solely by accuracy. However, nearly all retrieved evidence is synthetic, indicating a severe collapse in source diversity.

‘This divergence, characterized by stable accuracy despite collapsing diversity, reveals a structurally brittle retrieval pipeline: the system performs well in aggregate metrics while quietly losing its grounding in human-written content.

‘Overall, high-quality synthetic content not only integrates seamlessly into retrieval pipelines but actively overwhelms ranking signals, leading both BM25 and LLM Rankers to rely almost exclusively on AI-generated evidence.’

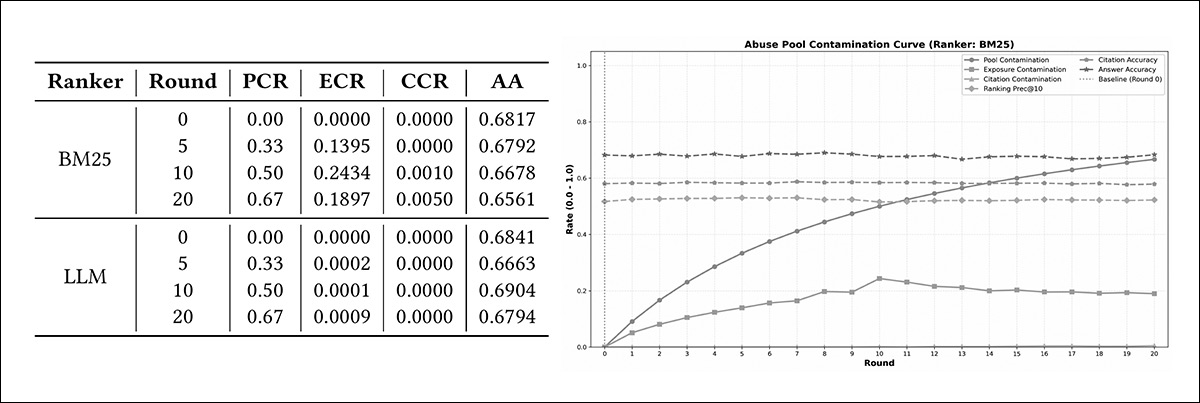

The second scenario was named Pollution and System Corruption, and revealed a notable divergence in ranker behavior, compared to the first scenario:

Left: the scenario 2 results show what happens when deliberately misleading pages are added to the system. As more of these pages are mixed in, BM25 begins to place some of them in its top results – though only up to about a quarter at the midpoint, and almost none are actually used in the final answer. Overall answer quality falls slightly. Right: the table presents the same pattern in numbers for both BM25 and the LLM-based ranker, making clear that BM25 lets some misleading pages into its top results, whereas the LLM ranker largely filters them out.

The LLM-based ranker was largely able to recognize and filter out misleading pages, keeping the share of such content in its top results close to zero; but BM25 allowed a noticeable portion of the adversarial pages to enter its top ten results, with roughly 19% to 24% appearing there at certain stages of the test.

Although the LLM ranker proved more resistant in this experiment, the authors note that LLM-based ranking systems are more computationally demanding, which can make large-scale deployment impractical. Though BM25 is simpler and cheaper to run, widely-used retrieval systems that leverage it may, the paper contends, be more exposed to manipulated content than they initially appear.

The authors characterize this as a ‘significant structural risk’.

In regard to the contrast between apparent stability and underlying degradation, the authors note that in this context, AA remains relatively stable, due to the LLM judge suppressing citation corruption, and therefore acting as a kind of last-moment firewall against adversarial content.

However, Answer Accuracy in this aspect was consistently lower than in the first scenario:

‘While Scenario 1 saw AA maintained or even improved (reaching up to 70% with LLM Rankers) due to the high quality of SEO content, Scenario 2 exhibits a decline in answer quality relative to the SEO setting […]

‘This confirms that regardless of the ranker, adversarial pollution in the retrieval stage negatively impacts end-to-end performance, with the degradation being most severe when relying on lightweight retrievers.’

The authors conclude that re-ranking at the retrieval stage is too tardy an approach, and that ‘ingestion-stage’ filters should be considered, proposing that ‘provenance graphs’ and ‘perplexity filters’ could be utilized.

They close by emphasizing that the core threat is content with high fluency but low attribution density, essentially divorced from reassuring chains of provenance, and observe:

‘[As] Agentic AI begins to autonomously publish content, defense mechanisms must evolve from static text analysis to behavioral fingerprinting, identifying and isolating agents that systematically produce high-entropy, low-factuality streams.’

Conclusion

The establishment of new or improved methodologies for information provenance may be one of the most critical necessities for 2026. Complex credential schemes such as the ailing C2PA, which require infrastructural changes from publishers, and public education about what they mean and how or why to use them, seem destined to fail.

Something simpler is required, and it has not been found yet. It’s an urgent mission, since this current era may be the most critical turning point for public consensus on truth since the invention of photography in 1822, and the rise of propaganda in the decades prior to WWII.

* My (selective, where necessary) conversion of the authors” inline citations to hyperlinks.

First published Thursday, February 19, 2026