Anderson's Angle

Adding Dialogue to Real Video With AI

A new AI framework can rewrite, remove or add a person’s words in video without reshooting, in a single end-to-end system.

Three years ago, the internet would have been stunned by any one of the 20-30 AI video-altering frameworks that get published in academic portals weekly; as it is, this popular strand of research has now become so prolific as to almost constitute another branch of ‘AI Slop’, and I cover far fewer of such releases than I would have two or three years back.

However one current release in this line caught my eye: an integrated system that can intervene in real video clips and interpose new speech into the existing video (rather than creating an entire generative clip from a face or frame, which is far more common).

In the examples below, which I edited together from a multitude of sample videos available at the release’s project website, we first see the real source clip, and then, underneath, the imposed AI speech in the middle of the clip, including voice synthesis and lip sync:

Click to play. Local editing with stitching – one several modalities offered by FacEDiT. Please refer to source website for better resolution. Source – https://facedit.github.io/

This approach is one of three developed for the new method, this one titled ‘local editing with stitching’, and the one which most interests the authors (as well as myself). Essentially the clip is extended by using one of the middle frames as a starting point for novel AI interpretation, and its successive (real) frame as a goal that the generative inserted clip should aim to match up to. In the clips seen above, these ‘seed’ and ‘target’ frames are represented by the uppermost video pausing while the amended video below provides generative infill.

The authors frame this facial and vocal synthesis approach as the first fully-integrated end-to-end method for AI video edits of this kind, observing the potential of a fully-developed framework such as this for TV and movie production:

‘Filmmakers and media producers often need to revise specific parts of recorded videos – perhaps a word was misspoken or the script changed after shooting. For instance, in the iconic scene from Titanic (1997) where Rose says, “I’ll never let go, Jack,” the director might later decide it should be “I’ll never forget you, Jack”.

‘Traditionally, such changes require reshooting the entire scene, which is costly and time-consuming. Talking face synthesis offers a practical alternative by automatically modifying facial motion to match revised speech, eliminating the need for reshoots.’

Though AI interpositions of this kind may face cultural or industry resistance, they may also constitute a new type of functionality in human-led VFX systems and tool suites. In any case, for the moment, the challenges are strictly technical.

Besides extending a clip through additional AI-generated dialogue, the new system can also alter existing speech:

Click to play. An example of changing existing dialogue rather than interposing additional dialogue. Please refer to source website for better resolution.

State of the Art

There are currently no end-to-end systems that offer this kind of synthesis capability; though a growing number of generative AI platforms such as Google’s Veo series, can generate audio, and diverse other frameworks can create deepfaked audio, one currently has to create a rather involved pipeline of diverse architectures and tricks in order to interfere with real footage in the way the new system – titled FacEDiT – can accomplish.

The system uses Diffusion Transformers (DiT) in combination with Flow Matching to create facial motions conditioned on surrounding (contextual) motions and speech audio content. The system leverages existing popular packages that deal with facial reconstruction, including LivePortrait (recently taken over by Kling).

In addition to this method, given that their approach is the first to integrate these challenges into a single solution, the authors have created a novel benchmark called FacEDiTBench, along with several entirely new evaluation metrics apposite to this very specific task.

The new work is titled FacEDiT: Unified Talking Face Editing and Generation via Facial Motion Infilling, and comes from four researchers across Korea’s Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH ), Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology (KAIST), and The University of Texas at Austin.

Method

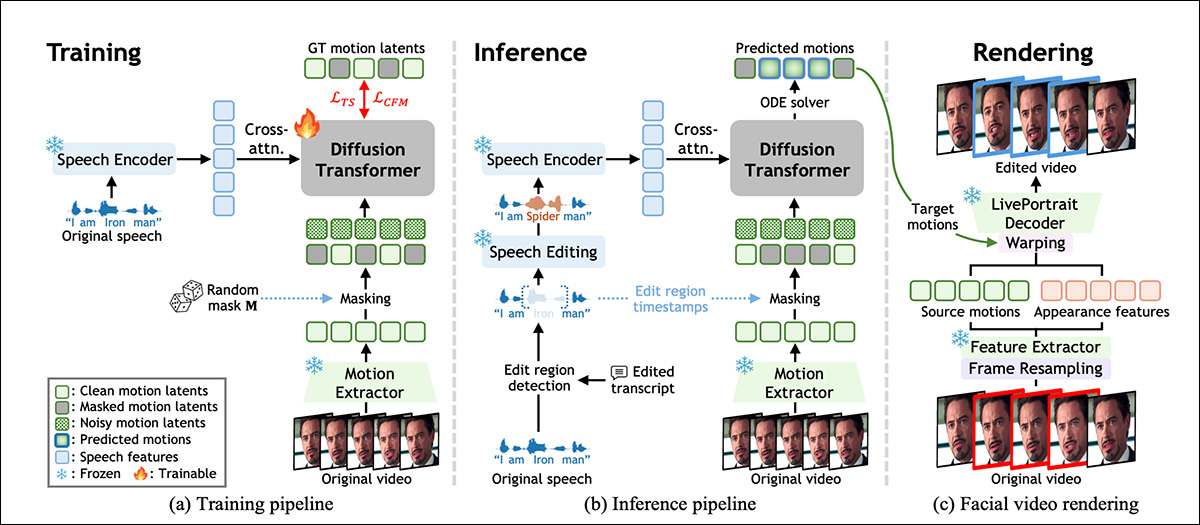

FacEDiT is trained to reconstruct facial motion by learning how to fill in missing parts of an actor’s original performance, based on the surrounding motion and the speech audio. As shown in the schema below, this process allows the model to act as a gap-filler during training, predicting facial movements that match the voice while staying consistent with the original video:

Overview of the FacEDiT system, showing how facial motion is learned through self‑supervised infilling during training, guided by edited speech at inference, and finally rendered back into video by reusing the appearance of the original footage, while replacing only the targeted motion. Source

At inference time, the same architecture supports two different outputs depending on how much of the video is masked: partial edits, where only a phrase is altered and the rest left untouched; or full-sentence generation, where new motion is synthesized entirely from scratch.

The model is trained via flow matching, which treats video edits as a kind of path between two versions of facial motion.

Instead of learning to guess what an edited face should look like from scratch, flow matching learns to move gradually and smoothly between a noisy placeholder and the correct motion. To facilitate this, the system represents facial motion as a compact set of numbers extracted from each frame using a version of the aforementioned LivePortrait system (see schema above).

These motion vectors are designed to describe expressions and head pose without entangling identity, so that speech changes can be localized without affecting the person’s overall appearance.

FacEDiT Training

To train FacEDiT, each video clip was broken into a series of facial motion snapshots, and each frame paired with the corresponding chunk of audio. Random parts of the motion data were then hidden, and the model asked to guess what those missing movements should look like, using both the speech and the surrounding unmasked motion for context.

Because the masked spans and their positions vary from one training example to the next, the model gradually learns how to handle both small internal edits, and longer gaps, for full-sequence generation, according to how much information it is given.

The system’s aforesaid Diffusion Transformer learns to recover masked motion by refining noisy inputs over time. Instead of feeding speech and motion into the model all at once, the audio is threaded into each processing block through cross-attention, helping the system match lip movements more precisely to the audio speech.

To preserve realism across edits, attention is biased toward neighboring frames rather than the entire timeline, forcing the model to focus on local continuity, and preventing flickers or motion jumps at the edges of altered regions. Positional embeddings (which tell the model where each frame appears in the sequence) further help the model to maintain natural temporal flow and context.

During training, the system learns to predict missing facial motion by reconstructing masked spans based on speech and nearby unmasked motion. At inference time, this same setup is reused, but with the masks now guided by edits in the speech.

When a word or phrase is inserted, removed, or changed, the system locates the affected region, masks it, and regenerates motion that matches the new audio. Full-sequence generation is treated as a special case, where the entire region is masked and synthesized from scratch.

Data and Tests

The system’s backbone comprises 22 layers for the Diffusion Transformer, each with 16 attention heads and feedforward dimensions of 1024 and 2024px. Motion and appearance features are extracted using frozen LivePortrait components, and speech encoded via WavLM and modified using VoiceCraft.

A dedicated projection layer maps the 786‑dimensional speech features into the DiT’s latent space, with only the DiT and projection modules trained from scratch.

Training was performed under the AdamW optimizer at a target learning rate of 1e‑4, for a million steps, on two A6000 GPUs (each with 48GB of VRAM), at a total batch size of eight.

FacEDiTBench

The FacEDiTBench dataset contains 250 examples, each with a video clip of the original and edited speech, and the transcripts for both. The videos come from three sources, with 100 clips from HDTF, 100 from Hallo3, and 50 from CelebV-Dub. Each was manually checked to confirm that both the audio and video were clear enough for evaluation.

GPT‑4o was used to revise each transcript to create grammatically valid edits. These revised transcripts, along with the original speech, were passed to VoiceCraft to produce new audio; and at each stage, both the transcript and the generated speech were manually reviewed for quality.

Each sample was labeled with the type of edit, the timing of the change, and the length of the modified span, and edits classified as insertions, deletions, or substitutions. The number of words changed ranged from short edits of 1 to 3 words, medium edits of 4 to 6 words, and longer edits of 7 to 10 words.

Three custom metrics were defined to evaluate editing quality. Photometric continuity, to measure how well the lighting and color of an edited segment blend with the surrounding video, by comparing pixel-level differences at the boundaries; motion continuity, to assess the consistency of facial movement, by measuring optical flow changes across edited and unedited frames; and identity preservation, to estimate whether the subject’s appearance remains consistent after editing, by comparing facial embeddings from the original and generated sequences using the ArcFace facial recognition model.

Tests

The testing model was trained on material from the three above-mentioned datasets, totaling around 200 hours of video content, including vlogs and movies, as well as high-resolution YouTube videos.

To evaluate talking face editing, FacEDiTBench was used, in addition to the HDTF test split, which has become a benchmarking standard for this suite of tasks.

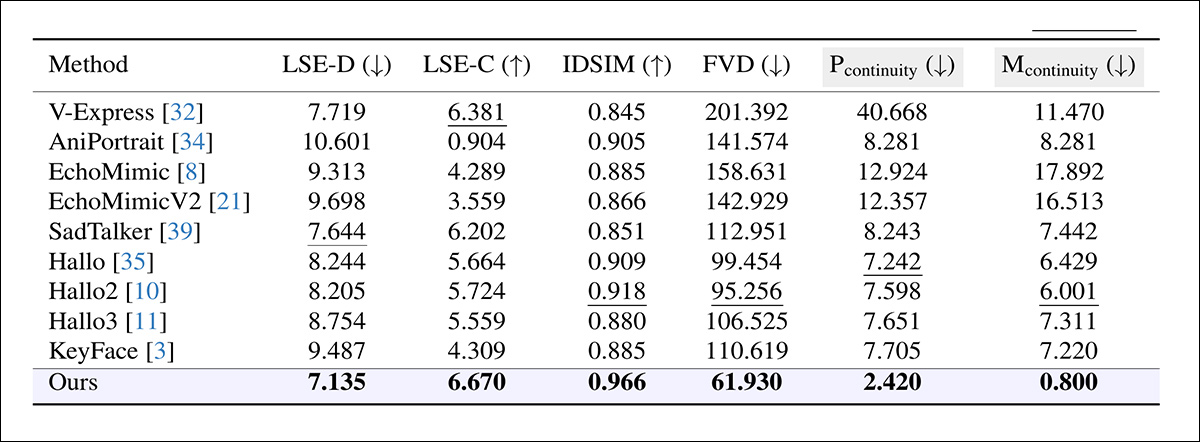

Since there were no directly comparable systems capable of encapsulating this kind of end-to-end functionality, the authors chose a variety of frameworks that reproduced at least some of the target functionality, and could operate as baselines; namely, KeyFace; EchoMimic; EchoMimicV2; Hallo; Hallo2; Hallo3; V-Express; AniPortrait; and SadTalker.

Several established metrics were also used to assess generation and editing quality, with lip-sync accuracy evaluated through SyncNet, reporting both the absolute error between lip movements and audio (LSE-D) and a confidence score (LSE-C); Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) quantifying how realistic the video appeared overall; and Learned Perceptual Similarity Metrics (LPIPS), measuring perceptual similarity between generated and original frames.

For editing, all metrics except LPIPS were applied only to the modified segment; for generation, the entire video was evaluated, with boundary continuity excluded.

Each model was made to synthesize a matching video segment, which was then spliced into the original clip (the researchers note that this method frequently introduced visible discontinuities, where the edited section met the surrounding footage). A second approach was also tested, in which the entire video was regenerated from the modified audio – but this inevitably overwrote unedited regions, and failed to preserve the original performance:

Comparison of editing performance across systems originally designed for talking face generation, with FacEDiT outperforming all baselines across every metric, achieving lower lip-sync error (LSE-D), higher synchronization confidence (LSE-C), stronger identity preservation (IDSIM), greater perceptual realism (FVD), and smoother transitions across edit boundaries (Pcontinuity, Mcontinuity). Gray-shaded columns highlight the key criteria for assessing boundary quality; bold and underlined values indicate the best and second-best results, respectively

Regarding these results, the authors comment:

‘[Our] model significantly outperforms existing methods on the editing task. It achieves strong boundary continuity and high identity preservation, demonstrating its ability to maintain temporal and visual consistency during editing. In addition, its superior lip-sync accuracy and low FVD reflect the realism of the synthesized video.’

Click to play. Results, assembled by this author from the published videos at the supporting project site. Please refer to source website for better resolution.

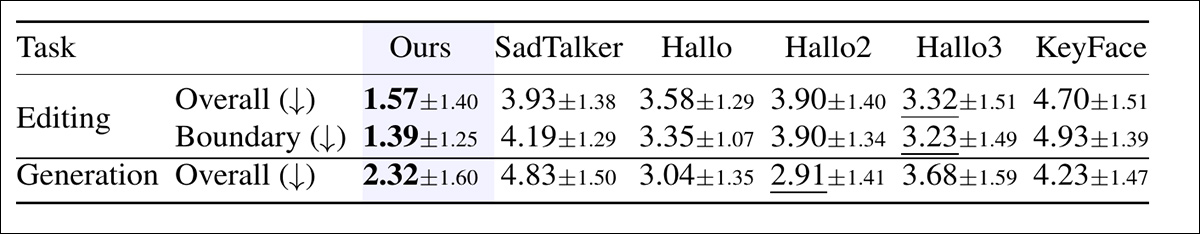

Further, a human study was conducted, to evaluate perceived quality across both editing and generation.

For each comparison, participants viewed six videos and ranked them by overall quality, considering lip-sync accuracy, naturalness, and realism of head motion. In editing trials, participants also rated the smoothness of transitions between edited and unedited segments:

Average ranks assigned by human evaluators, where lower means better. In both editing and generation, participants judged how natural and well-synced each video looked. For editing, they also rated how smooth the transition was between edited and unedited speech.Bold and underlined numbers indicate the top two scores.

In the study, FacEDiT was consistently ranked highest by a clear lead, for both edit quality and transition seamlessness, also receiving strong scores in the generation setting, suggesting that its measured advantages translate into perceptually preferred outputs.

Due to lack of space, we refer the reader to the source paper for further details of ablation studies, and additional tests that were run and reported in the new work. In truth, prototypical research offerings of this kind struggle to generate meaningful test results sections, since the core offering itself is inevitably a potential baseline for later work.

Conclusion

Even for inference, systems such as this may require significant compute resources at inference time, making it difficult for downstream users – here, presumably, VFX shops – to keep the work on premises. Therefore approaches which can be adapted to realistic local resources will always be preferred by providers, which are under legal obligation to protect client’s footage and general IP.

That’s not to criticize the new offering, which may very well operate perfectly under quantized weights or other optimizations, and which is the first offering of its kind to attract me back to this avenue of research in quite some time.

First published Wednesday, December 17, 202. Edited 20.10 EET, same day, for extra space in first body para.