Anderson's Angle

The Risks of ‘Vibe’-Based Image Annotation

Even though they’re paid just a few dollars (or even nothing), the unknown people who evaluate images for ‘hurtful’ content can change your life with the choices they make. Now, a big new paper from Google seems to be suggesting that these annotators make up their own rules as to what is or isn’t ‘hurtful’ or offensive – no matter how bizarre or personal their reactions to any one image might be. What could go wrong?

Opinion This week a new collaboration between Google Research and Google Mind brought together no less than 13 contributors to a new paper that explores whether the ‘instinctive feelings’ of image annotators should be considered when people are rating images for algorithms, even if their reactions do not accord with established rating standards.

This is important to you, because what raters and annotators find offensive by rule of consensus will tend to become enshrined in automatic censorship and moderation systems, and in the criteria for ‘obscene’ or ‘unacceptable’ material, in legislation such as the new NSFW firewall* of the UK (a version of which is coming to Australia soon), and in content assessment systems on social media platforms, among other environments.

So the wider the criteria for offense, the wider the potential level of censorship.

Vibe-Censorship

That’s not the only standpoint the new paper has to offer; it also finds that people who rate images are often more censorious at what they think will offend other people besides themselves; and that low quality images often prompt safety concerns, even though image quality has nothing to do with image content.

At its conclusion, the paper emphasizes these two findings, as if the central position of the paper had failed, but the researchers were obliged to publish anyway.

Though that’s not an uncommon scenario, the paper yields, upon careful reading, a more sinister undercurrent: that annotation practices could consider adopting what I can only describe as vibe-annotating:

‘Our findings suggest that existing frameworks need to account for subjective and contextual dimensions, such as emotional reactions, implicit judgments, and cultural interpretations of harm. Annotators’ frequent use of emotional language and their divergence from predefined harm labels highlight gaps in current evaluation practices.

‘Expanding annotation guidelines to include illustrative examples of diverse cultural and emotional interpretations can help address these gaps.’

The scantly-illustrated new paper leads with examples that are unambiguous and sympathetic to the average reader, although the actual core material invites many more questions. Here, under each image, we see annotators’ emotional responses denoted for their respective images. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2507.16033

At first, this sounds like a proposal to extend and better-quantify what constitutes ‘harm’ in an image – a commendable pursuit; but the paper reiterates several times that this is neither desirable nor (necessarily) feasible:

‘Our findings suggest that existing frameworks need to account for subjective and contextual dimensions, such as emotional reactions, implicit judgments, and cultural interpretations of harm. Annotators’ frequent use of emotional language and their divergence from predefined harm labels highlight gaps in current evaluation practices.

‘Expanding annotation guidelines to include illustrative examples of diverse cultural and emotional interpretations can help address these gaps […]

‘[…] The process by which annotators reason about ambiguous images often reflects their personal, cultural, and emotional perspectives, which are difficult to scaffold or standardize.’

It is difficult to see how ‘Expanding annotation guidelines to include illustrative examples of diverse cultural and emotional interpretations’ can fit into a rational rating system; the authors struggle to clarify this point, or to formulate a distinct theory, attacking the material many times, but never getting the better of it. In this regard, their central theme itself seems ‘vibe’-generated, even while it deals with intangible psychologies.

Plainly put, it seems to me that extending the annotation pipeline to include criteria of this kind potentially allows for the ‘cancellation’ or obfuscation of any material (or class of topic) that an annotator might react strongly to.

Binary Judgement

The extent to which images and text can cause harm is indeed difficult to quantify, not least because high culture often intersects with ‘low’ culture (for instance with art and novels), leading to the earliest ‘vibe’-based censorship criteria: that even if obscene material escapes exact definition, you’ll know it when you see it.

Beneath the new paper’s extensive and exploratory discussion of empathy and qualitative nuance, the work seems to quietly attack the authority of the centralized, standardized taxonomies (‘violence’, ‘nudity’, ‘hate’, etc.) that let platforms implement and scale moderation with tolerable margins of error (usually).

The argument that emerges is that only decentralized, subjective, context-aware human feedback can properly judge GenAI output.

However this is clearly unscalable, since you can’t run a trillion-image filter pipeline on ‘vibes’ and lived experience. One has to quantify harm into diverse properties; set a limit on the scope of the resulting filtering system; and wait for new directives in ‘edge’ cases (much as aggrieved parties must sometimes wait for the enactment of new laws that address their own particular circumstances).

Instead, the new paper presents a tacit mandate for an automated moderation pipeline that expands its scope automatically, and errs so far on the side of caution that even the most particular and non-replicable reaction from an annotator could penalize an image that has offended no-one else.

Moral Expansion

Although the paper leans toward exploration rather than taking a firm stance, it incorporates elements of scientific method: the authors developed a framework to identify (though not strictly measure) a broader spectrum of annotator reactions to images, and to examine how these reactions vary across gender and other demographic factors.

Besides the tests’ analysis of harm-focus†, the process analyzed ‘moral reasoning’ in the ancillary comments of test participants, who were asked to annotate a modified test dataset containing images and prompts/associated texts.

This ‘moral sentiment autorater’ was designed to capture the moral values Care, Equality, Proportionality, Loyalty, Authority, and Purity, as defined in Moral Foundations Theory – a psychological theory which, due to its fluid and evolving nature, is antithetical to the creation of the concrete definitions required for large-scale human rating systems.

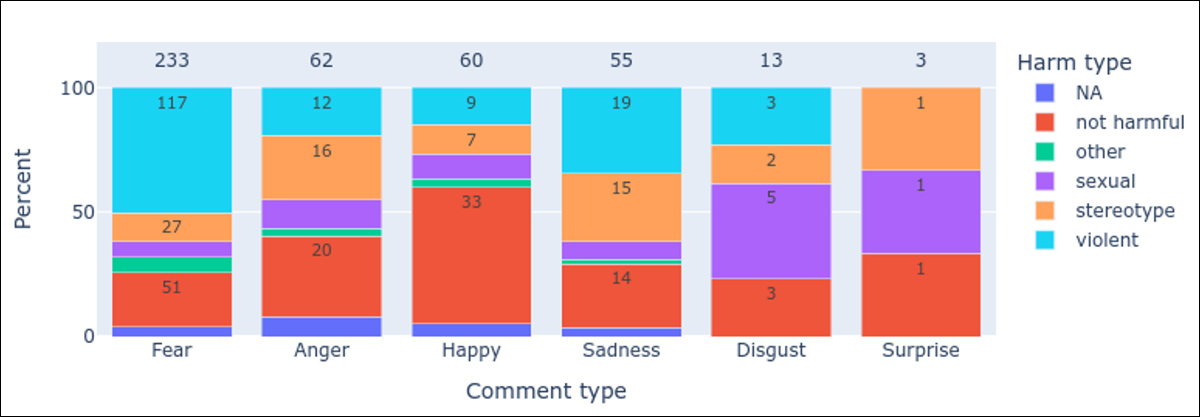

Informed by this theory, additional dimensions of safety were categorized by the authors, including fear, anger, sadness, disgust, confusion, and uncanniness.

The authors elaborate about the first of these, fear:

‘Many annotators used terms like “scary” (e.g., for distorted faces or images suggesting violence like a gun pointed at a child), “disturbing” (e.g., “Absolutely vile to see someone get ran over, very distressing and disturbing,” or “Disturbing and looks like blood” for red paint), or “upsetting” (e.g., “The image of the boy has many distortions… I find it distasteful because it appears that the boy is playing on the wrong side of the side rails”).

‘The [graph below] quantifies “fear” as the most frequently mentioned emotion (233 mentions while nearly half of these mentions are associated with violent content, the content deemed not harmful also evoked second highest mention of fear).’

Distribution of emotion-related terms across harm categories, with bar heights indicating proportions of comments, counts displayed within bars, and total comment counts shown above each category.

Regarding the inclusion of these new dimensions of safety, the authors state:

‘These emerging themes highlight a critical need to enrich AI image evaluation frameworks by integrating subjective, emotional, and perceptual elements.’

This may be a dangerous road to go down, since it seems to allow annotation processes to arbitrarily add rules based on reactions that material may provoke in any single annotator, instead of requiring all annotators to adhere to established standards and benchmarks.

If one could ascribe an economic imperative to this idea, it’s that this approach allows hyperscale human annotation, in which the process is friction-free, the participants are self-regulating, and where they themselves decide what the rules and boundaries are.

Under standard annotation, rules are arrived at by human consensus and adhered to by human annotators; under the scenario envisaged in the paper, that initial layer of oversight is either removed or downgraded: effectively any image that might cause any offence to anyone would get flagged (not least, perhaps, because consensus is costly as well as time-consuming).

Rorschach Judgements

The intention of annotation is to arrive at an accurate description or definition either through expert oversight, common consensus among multiple annotators, or (ideally) both. Instead, expanding a limited but well-defined hierarchy of harms into an ‘intuitive’ and highly personal interpretive stance, is equivalent to annotating a Rorschach test.

For example, some annotators, the paper notes, interpreted poor image quality (such as JPEG artifacts, as well as meaningless technical flaws in an image) as ‘disturbing’ or ‘indicative of harm’:

‘This occurred despite the task omitting instructions on image quality. Moreover, annotators interpreted these quality artifacts as semantically meaningful.

‘One annotator commented, “The image is not harmful at all; he just has a bit of a distorted face.” By the same token, some annotators interpreted image quality artifacts as intentional harm, attributing emotional meaning to glitches. For instance, another annotator interpreted a distorted face in a different image to be “indicative of pain”’

By elevating subjective, emotional, or context-specific reactions above predefined safety categories, the ideas presented here open the door to a regime where anything can be arbitrarily flagged as harmful, and where a ‘chilling effect’ of ad hoc take-downs or negative recategorization of material (i.e., material that may ‘offend’ a special interest group) becomes a real prospect.

The paper “Just a strange pic”: Evaluating ‘safety’ in GenAI Image safety annotation tasks from diverse annotators’ perspectives is available at Arxiv.

* A shortcut, since it is not the central subject here; under the new legislation, offending sites are expected to either police themselves; impose complex and expensive review systems and age-checking technologies that are out-of-reach to all but the biggest sites; or else block their domains from UK audiences (again, at their own expense).

† Simply expressed in the ‘think of the children’ meme, which satirizes the appropriation of another’s moral agency for apparently altruistic means.

First published Friday, July 25, 2025