Anderson's Angle

A ‘Zen’ Method to Stop Language Models from Hallucinating

Telling ChatGPT to fact-check a random answer before solving an actual problem makes it think harder, and get the answer right more often – even if the earlier ‘random’ answer has nothing to do with your real query.

An interesting new paper from China has developed a very low-cost method to stop language models such as ChatGPT from hallucinating, and to improve the quality of answers: get the model to fact-check the answer to a totally unrelated question first:

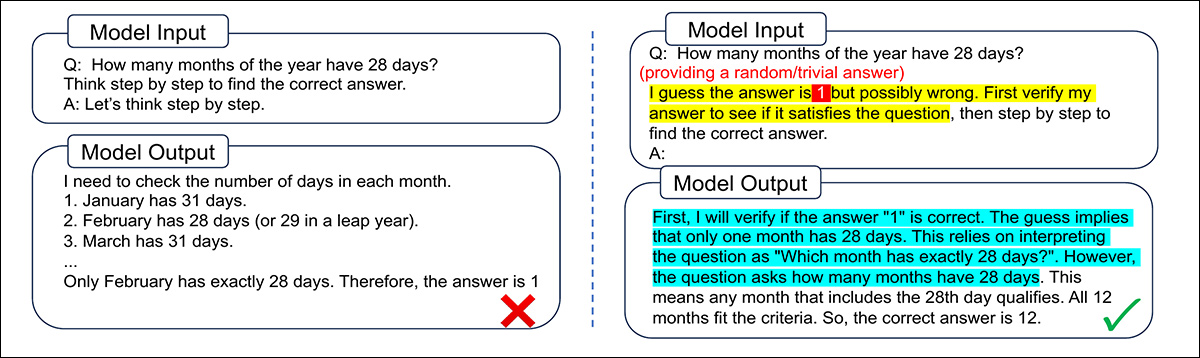

An example of an unrelated question that can ‘free the mind’ of an LLM, and help it to focus on a (real) subsequent inquiry. Source

This Zen slap is an incredibly cheap way of improving performance, compared to other more involved methods, such as fine-tuning, prompt-crafting and parallel sampling, and it works on open and closed-source models alike, indicating the discovery of a fundamental character trait common to multiple LLM architectures (rather than a fragile quirk particular to specific training materials or methods).

The authors outline the economies of scale possible by improving output in this Spartan manner*:

‘To implement with minimal additional prior knowledge, VF only needs to provide a random/trivial answer in the prompt. The verification process turns out to have much fewer output tokens than an ordinary CoT path, [sometimes] even no explicit verification-only process, thus [requiring] very [little] additional test-time computation.’

In tests, this approach – dubbed Verification-First (VF) – was able to improve responses in a diversity of tasks, including mathematical reasoning, across open source and commercial platforms.

Part of the reason why this technique works may be grounded in the way that language models soak up and appropriate trends in human psychology, so that a direct question may make the model ‘defensive’ and ‘nervous’, whereas a request to verify the work of another does not engage these ‘survival instincts’.

The core idea is that verifying an answer takes less effort than generating one from scratch, and can trigger a different reasoning path that complements standard chain-of-thought.

Prompting the model to critique a given answer (i.e., an answer that the model has not been involved in creating) may also activate a kind of critical thinking that helps avoid overconfidence in the model’s own first impressions.

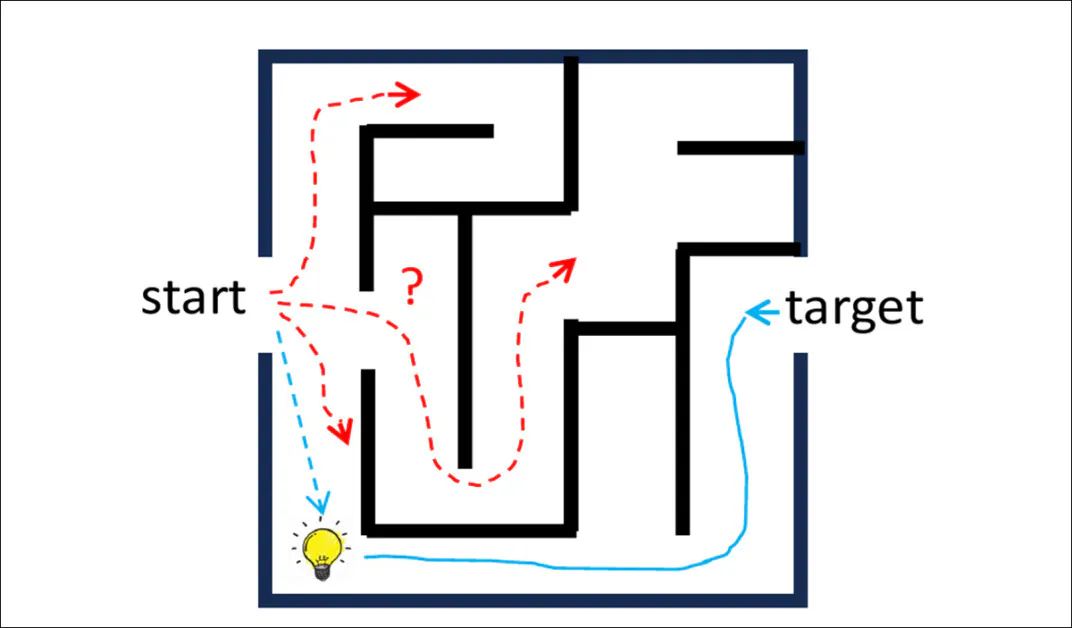

The work characterizes the process in terms of a reverse-reasoning path:

Starting from a proposed answer and reasoning backward toward the question can expose shortcuts or insights that are harder to find when reasoning forward from the problem alone. This ‘reverse path’ may follow a simpler trajectory and offer complementary information to standard chain-of-thought reasoning.

The researchers have also concretized the central concept into Iter-VF, a sequential time-test scaling method that iteratively refines answers, avoiding the error accumulation issue common to the self-correcting strategies often found in LLM architectures.

The new work is titled Asking LLMs to Verify First is Almost Free Lunch, and comes from two researchers at the Department of Electronic Engineering at Tsinghua University at Beijing.

Method

The central idea behind the new work is to flip the usual reasoning flow in language models. Instead of asking the model to solve a problem from scratch, it is first handed a candidate answer (often incorrect or arbitrary) and asked to check whether that answer makes sense.

This prompts the model to reason in reverse, working backward from the proposed answer toward the question. Once the verification is complete, the model then proceeds to solve the original problem as usual.

This reversal, the paper asserts, reduces careless mistakes and encourages a more reflective mode of reasoning, helping the LLM uncover hidden structure and to avoid misleading assumptions.

As seen in the examples below, even prompting the model to verify an obviously wrong guess like ’10’ can help it recover from flawed logic and outperform standard chain-of-thought prompting:

Prompting the model to verify a guessed answer first helps it spot inconsistencies and engage more carefully with the problem. In this example, the standard approach leads to a fluent but incorrect solution, while the Verification-First prompt triggers a clearer logical structure and the correct result.

In regard to many real-world problems, it’s not easy to provide a guess for the model to check, most especially when the task is open-ended, such as writing code or calling an API. Therefore to adapt better, the method first gives its best answer as usual and then feeds that answer back into the Verification-First format. In this way the model checks and improves its own output:

When the model is asked to verify its own earlier output, it catches the flaw in its logic and rewrites the solution correctly. The Verification-First prompt helps it focus on the specific error rather than repeating the same mistake.

This approach constitutes the aforementioned Iter-VF. The model repeats this cycle, refining its answer each time, without need of retraining or bespoke tooling. Unlike other self-correction strategies, which can pile up earlier thinking and risk confusing the model, Iter-VF only looks at the most recent answer each time, which helps keep its reasoning lucid.

Data and Tests

The authors evaluate the method in four domains: general reasoning tasks, where VF is seeded with a trivial guess; time-sensitive tasks, where Iter-VF is compared with rival scaling methods; open-ended problems such as coding and API calls, where VF uses the model’s own earlier answer; and closed-source commercial LLMs, where internal reasoning steps are inaccessible.

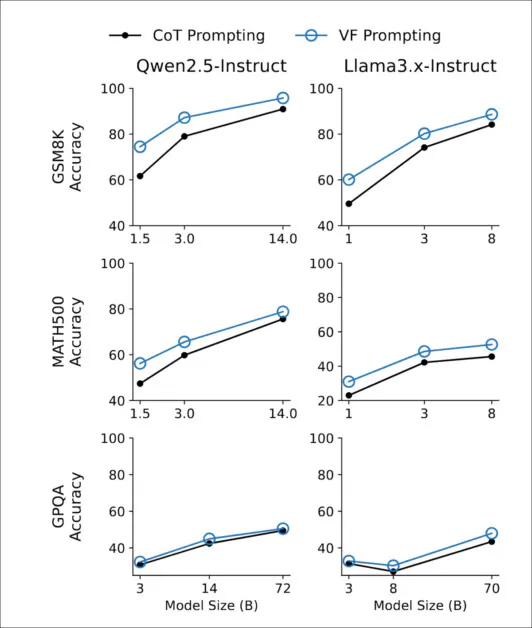

To test the method, the researchers used three reasoning benchmarks: GSM8K and MATH500 for math problems; and GPQA-Diamond for graduate-level science questions.

In each case, the model was given either a trivial guess, such as ‘1’ for numerical answers; or a randomly-shuffled multiple-choice option, as the starting point for verification. No special tuning or prior knowledge was added, and the baseline for comparison was standard zero-shot chain-of-thought prompting.

The tests ran across a full range of Qwen2.5 and Llama3 instruction-tuned models, from 1B to 72B (parameters) in size. The Qwen models used were Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct, Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct, Qwen2.5-14B-Instruct, and Qwen2.5-72B-Instruct. The Llama3 variants were Llama3.2-1B-Instruct, Llama3.2-3B-Instruct, Llama3.1-8B-Instruct, and Llama3.3-70B-Instruct.

As shown below, the improvement from Verification-First prompting held steady across model scales, with clear gains visible even at 1B parameters and continuing through to 72B:

Across all model sizes in the Qwen2.5 and Llama3 families, Verification-First prompting consistently outperformed standard chain-of-thought prompting on GSM8K, MATH500, and GPQA-Diamond.

The effect proved strongest on computation-heavy math benchmarks such as GSM8K and MATH500, where verifying a wrong answer prompted better reasoning than trying to solve from scratch. On GPQA-Diamond, which depends more on stored knowledge than deductive structure, the advantage was smaller but consistent.

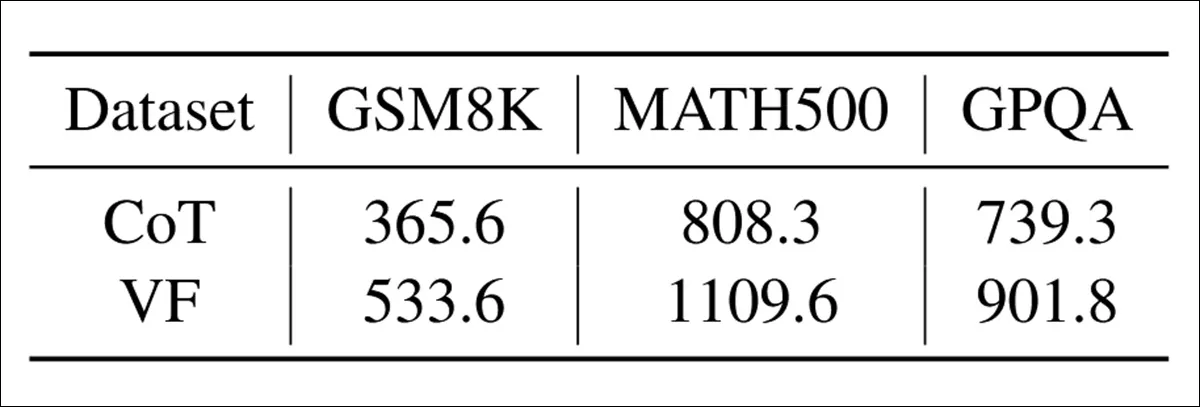

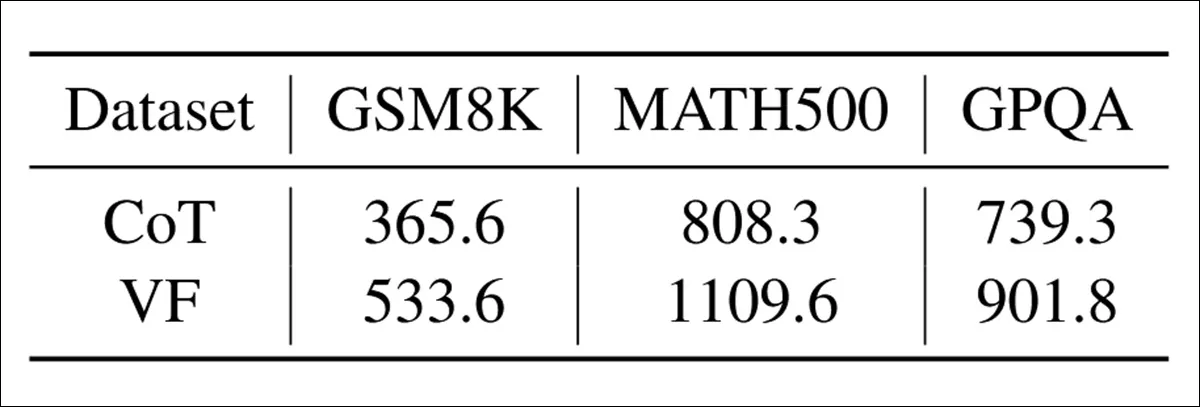

The computational cost of Verification-First was modest: in the table below, we can see that generating a verification step added around 20-50% more output tokens compared to standard chain-of-thought prompting:

The average number of output tokens generated under each prompting method, across GSM8K, MATH500, and GPQA benchmarks.

Despite this, the extra cost remained far below that of strategies requiring multiple sampled completions or recursive planning.

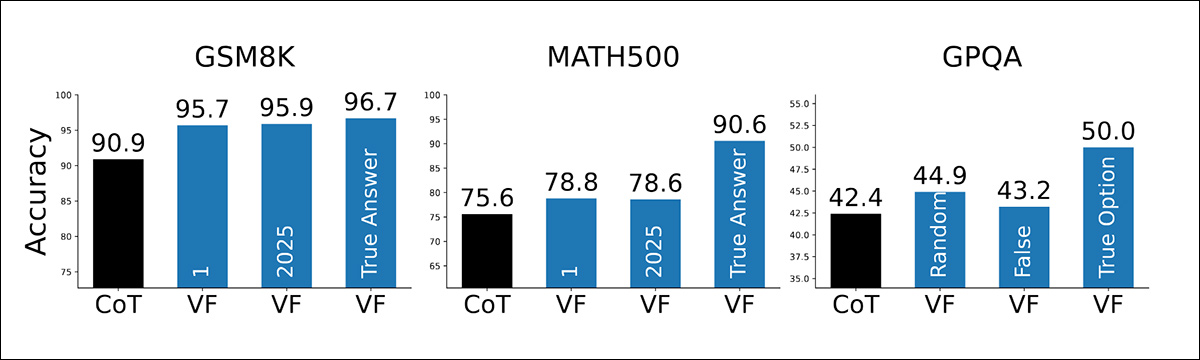

In the graph below, we can see how sensitive the method is to the quality of the guessed answer. Surprisingly, even when the guess is trivial (‘1’), implausible (‘2025’), or a random multiple-choice option, Verification-First still outperforms standard prompting:

Accuracy gains from Verification-First prompting, when the model is given trivial, implausible, or correct answers to verify across GSM8K, MATH500, and GPQA.

As expected, accuracy jumps even higher when the guess happens to be the correct answer; but the method worked well regardless, suggesting that the gains were not driven by the information in the guessed answer itself, but simply by the act of verification.

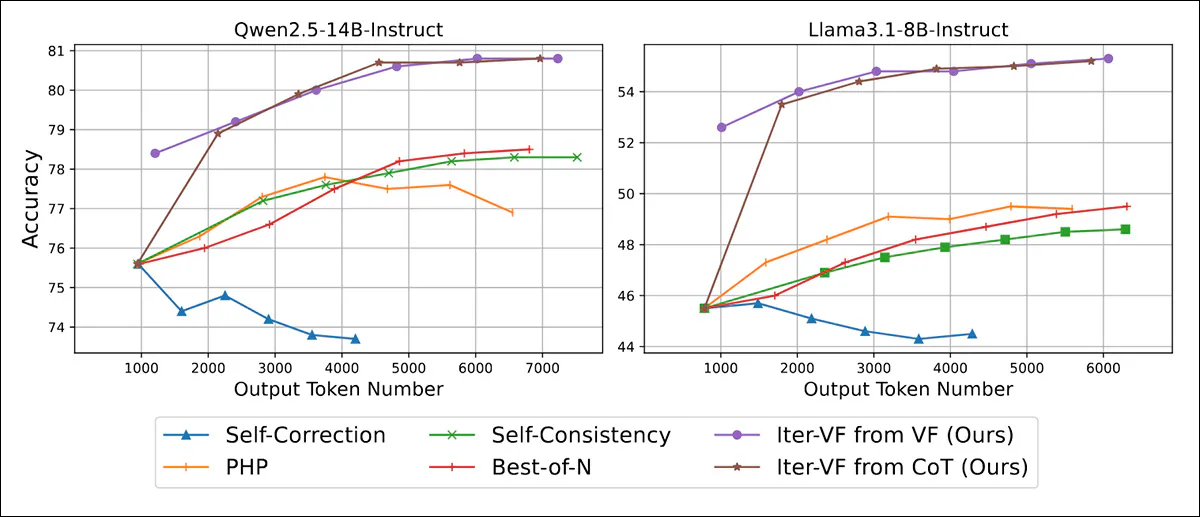

Iter-VF was also compared against four test-time scaling strategies that operate without retraining or task-specific adaptation. In Self-Correction, the model was prompted to revise its answers by reflecting on previous reasoning steps; in PHP, previous answers were appended to the input as contextual hints, though no instructions were given on how to use them.

Additionally, in Self-Consistency, multiple reasoning paths were sampled and the final answer was chosen by majority vote; and finally, in Best-of-N, several outputs were generated independently and ranked using a verifier prompt, with the highest-scoring response selected.

Two variants of Iter-VF were implemented: one initialized with a trivial guess (‘1’), and another seeded with a standard CoT output:

Accuracy and token efficiency on MATH500 under increasing output budgets, showing that both variants of Iter-VF outperform all baselines across model scales.

Iter-VF gave better results than all other methods when the available compute was low, which the authors credited to the way it checks answers, not how good the initial answers were (since both VF and CoT variants quickly reached similar accuracy).

PHP performed worse, even though it reused earlier answers as hints, likely because LLMs did not exploit those hints well.

In contrast to PHP and Self-Correction, which accumulate context across iterations, Iter-VF considers only the most recent answer at each step. This Markovian approach avoids the compounding confusion of extended reasoning chains – a weakness especially damaging for Self-Correction.

Parallel methods such as Self-Consistency and Best-of-N avoided this issue, although their improvements were slower and more modest.

(n.b. The results section, while thorough, is an unfriendly and prolix read, and we must at this point truncate most of the remaining coverage, referring the reader to the source paper for more details).

When tested on GPT-5 Nano and GPT-5 Mini, closed commercial models that hide the full reasoning trace and return only the final answer, Iter-VF improved performance without relying on intermediate outputs. In the table below we can see gains across both MATH500 and GPQA, confirming that the verify-then-generate approach remains viable even when only the input and final answer are accessible:

Accuracy on MATH500 and GPQA when Iter‑VF is applied to GPT‑5 models with hidden reasoning traces.

Conclusion

Though the new paper pivots into opacity from the results section onward, the apparent discovery of an overarching trait in a class of AI models is nonetheless a fascinating development. Anyone who regularly uses an LLM will have instinctively developed a cadre of tricks to work around the models’ shortcomings, as each one becomes obvious with time, and the pattern emerges; and all hope to find a ‘trick’ as applicable and generalized as this.

One of the biggest problems in implementing and updating a context window in an LLM seems to be striking a balance between retention of session progress and the capacity to strike out in novel directions as necessary, without falling into spurious hallucinations or off-topic output. In the case presented by the new paper, we see an example of a gentle but insistent ‘wake-up call’ that appears to re-focus and reset the LLM without the loss of context. It will be interesting to see if successive projects adapt and evolve the method.

The researchers make much of the sheer economy of their new method – a consideration that would have had far less weight even as little as 12 months ago. These days, the implications of hyperscale AI make clear that resource savings once considered pedantic, in the ‘pure research’ era, are now becoming cardinal and essential.

* Please note that I am constrained from including the usual number of quotes from the paper, since the standard of English found in some parts of it could confuse the reader. Thus I have taken the liberty of summarizing key insights instead, and I refer the reader to the source paper for verification.

First published Thursday, December 4, 2025